By Steven Hoelscher and Andrea Gustavson

When photographer Bruce Davidson boarded a Greyhound bus on May 24, 1961 in Montgomery, Alabama, he joined a group of 27 students, ministers, and activists determined to challenge the South’s segregation laws. In response to two earlier busses carrying anti-segregationist Freedom Riders—the first one firebombed and the second attacked by a mob wielding iron pipes—the federal government stepped in and ordered armed National Guard soldiers to provide protection. It was a moment of high drama in the Civil Rights movement, one that both exposed the bitter racism along the way from Montgomery to Jackson, Mississippi, and one that sorely tested the activists’ belief in nonviolent action. Davidson’s photographs portray something of that drama as they show a secret meeting before the ride, young men and women waiting to board the bus at the segregated station, groups along the route including white men heckling the Freedom Riders and black residents standing among National Guardsmen.

One picture succinctly captures the complicated emotions and political tensions of the scene: taken from inside the bus looking out, it portrays both the young activists and the armed escort ordered to protect them (above). This photograph, and others like it, circulated widely from the November 12, 1961 issue of The New York Times, to Raymond Arsenault’s 2007 Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, and to the cover of Davidson’s own 2002 book, Time of Change: Civil Rights Photographs, 1961-1965. An icon of the Freedom Riders’ struggle, it is featured on the 2010 American Experience documentary website.

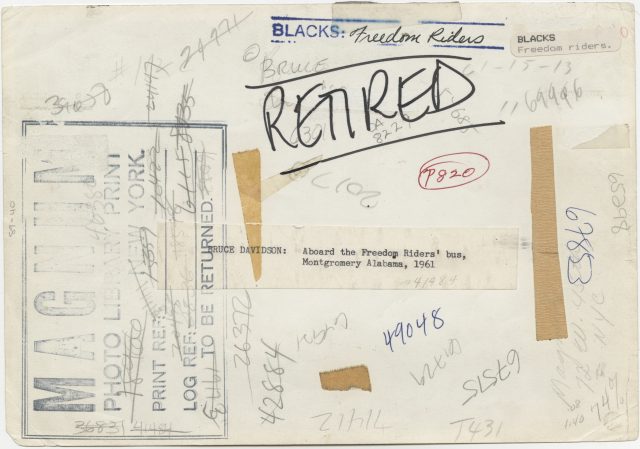

Verso from press print by Bruce Davidson, taken “aboard the Freedom Riders’ bus, Montgromery [sic] Alabama, 1961.” Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

Like the print itself, the collection of photographs to which it belongs is now also retired—at least from its previous occupation of carrying the image it bears to publishing venues. Davidson’s print came out of retirement in the summer of 2010—or, more accurately, it took on a new life—when the Magnum Photo New York Print Library was opened for research at the Harry Ransom Center, a research library and museum at the University of Texas at Austin. The Magnum Photos collection, as it is now known, is comprised of some 1,300 boxes containing more than 200,000 press prints and exhibition photographs by some of the twentieth century’s most famous photographers. Once Magnum began using digital distribution methods for its photographs, the function of press prints as vehicles for conveying the image became obsolete and these photographs became significant solely as objects for both monetary and historic value.

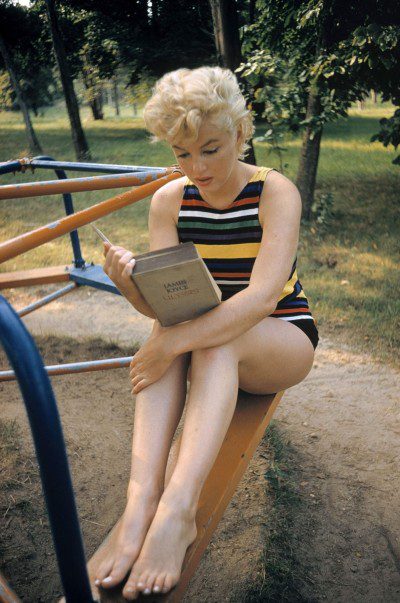

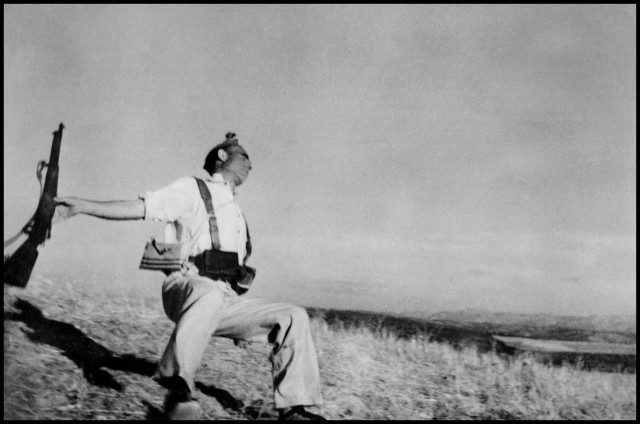

Magnum’s visual archive is a vast, living chronicle of the people, places, and events of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Images of cultural icons, from James Dean and Marilyn Monroe,to Gandhi and Castro, coexist in the Magnum Photos collection with depictions of international conflicts, political unrest, and cultural life. Included are famous war photos from the Spanish Civil War and D-Day landings to wars in Central America, Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as unforgettable scenes of historic events: the rise of democracy in India, the Chinese military suppression of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, the U.S. Civil Rights movement, the Iranian revolution, and the September 11 terrorist attacks.

Marilyn Monroe reading James Joyce’s Ulysses. Long Island, New York, 1955, ©Eve Arnold/Magnum Photos

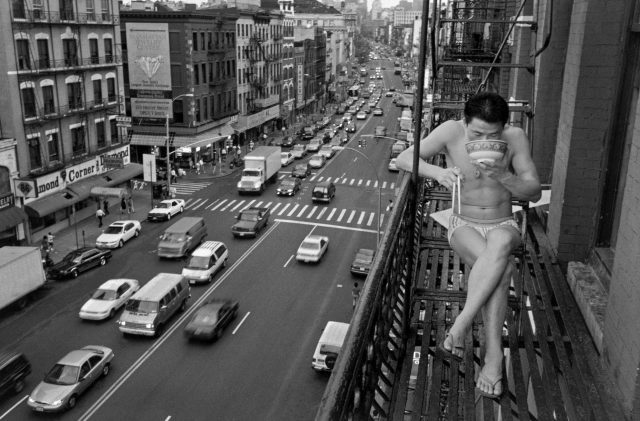

Finally, scenes of everyday life in a wide range of historical contexts—from immigrant communities in New York City to Romani communities in Czechoslovakia, and much more—comprise an extraordinarily valuable visual archive.

A newly arrived immigrant (Tang Z) eats noodles on a fire escape. New York City, 1998, ©Chien-Chi Chang/Magnum Photos

Magnum Photos was formed in 1947, in the wake of the Second World War, by four photographers seeking to retain the rights to their images while working on projects that aligned with their own interests rather than solely responding to commissions from magazines and newspapers. Henri Cartier-Bresson, David “Chim” Seymour, George Rodger, and Robert Capa created a business model that fundamentally changed the practices of photojournalism, allowing the image-maker, rather than the magazine, to retain control over published work. This shift allowed Magnum photographers to emphasize their artistic integrity and fosters independence in terms of subject matter.

Soldiers search bus passengers along the Northern Highway in El Salvador, 1980 by Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos.

The result was a new way of doing assignment photography so that members of the Magnum collective were free to pursue projects that spoke to their personal, political, and artistic concerns. While Magnum’s working model has evolved over time, Capa’s initial idea was that members would place images, often in the form of extended photo-essays, in various publications and across several geographic markets. The publication fees earned would be shared between the photographer and the agency with part of the earnings made available to finance further projects. Although Magnum Photos was formed during and sustained by the postwar heyday of picture magazines such as Life, Look, Picture Post, and Illustrated, the cooperative still exists and recently celebrated its 65th anniversary.

A column of T59 tanks makes its way from Tiananmen Square along the Avenue of Eternal Peace. A solitary protester stands determined in the center of the road, blocking the tanks. Beijing, China, June 4, 1989, ©Stuart Franklin/Magnum Photos

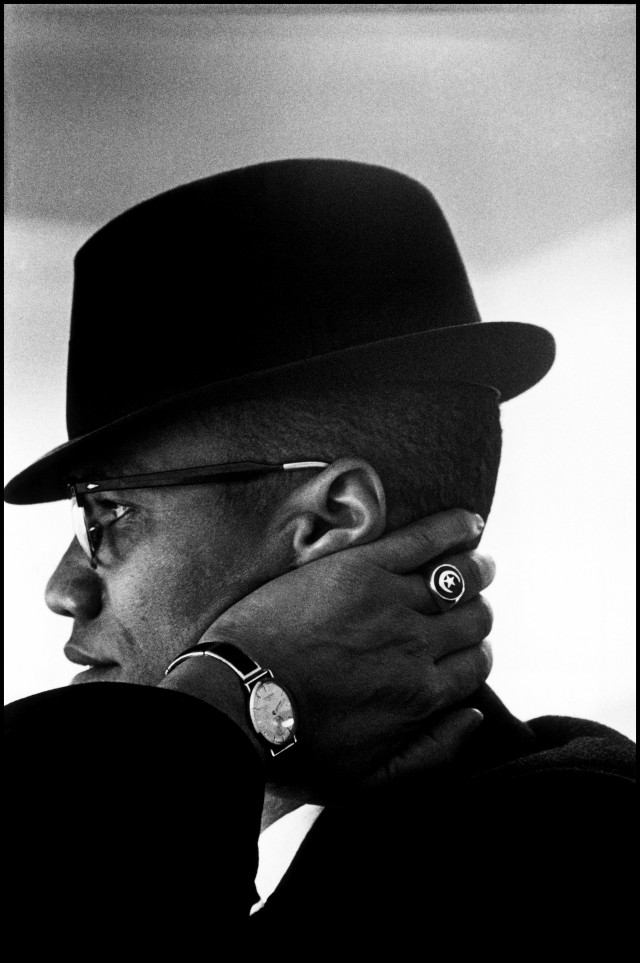

The organization of the Magnum Photos collection at the Harry Ransom Center directly reflects the working practices of the photography collective. A key component of Capa’s plan was the repackaging, recaptioning, and redistributing of images as photo-essays once the images were no longer immediately newsworthy. Practically speaking, this meant that images like Eve Arnold’s iconic photograph of Malcolm X might have been made into multiple prints and filed in several different file folders that eventually were placed into archival boxes including the box designated “Eve Arnold 1961-1964,” another designated “X, Malcolm 1925-1965,” and a third designated “Historical 1960s,” and a fourth designated “Social Protest.”

Malcolm X during his visit to enterprises owned by Black Muslims. Chicago, IL, 1962, ©Eve Arnold/Magnum Photos.

Eventually the physical photographs were returned to the Magnum office to be stored in file cabinets and boxes labeled by photographer and by a range of subjects and thematic groupings. This organizational structure has been preserved in the archival collection at the Ransom Center. The 169-page finding aid has sections for individual photographers, public personalities, and geographic regions. It also contains subject groupings such as “World War II” or “Motherhood” or “National parks” and also more idiosyncratic thematic categories such as “Time and Measurement” or “Historical Emotions, 1970s.”

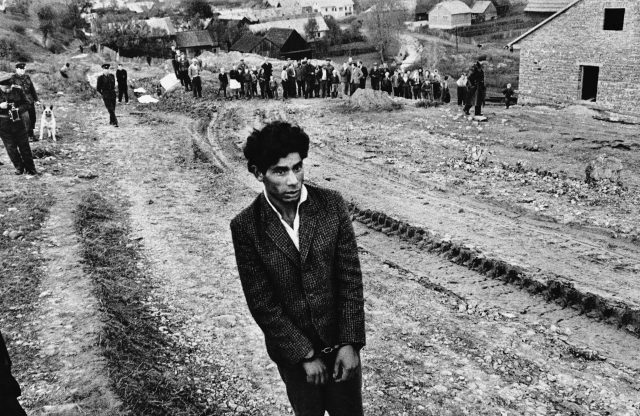

Reconstruction of a homicide. In the foreground: a young gypsy suspected of being guilty. Jarabina, Czechoslovakia, 1963, ©Josef Koudelka/Magnum Photos

These subject categories evolved along with the press print library as different librarians, archivists, and interns sought to structure the collection in ways that would make the images accessible and reusable. In this way, the press print library with its organizational structures and its multiple copies of each photograph was an attempt to make the objects—the press prints—function in service of the image content.

Historians are encouraged to visit the Reading and Viewing Room at the Harry Ransom Center, where the Magnum Photos collection is open for scholarly research and teaching and fellowships are available to support that research. To be sure, many of Magnum’s images are available online through its website. But to understand these photographs in their historical context—both how they circulated throughout the world and how the photo agency kept them in the public’s eye—direct engagement with these remarkable primary sources is essential.

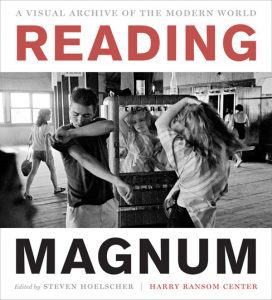

Reading Magnum: A Visual Archive of the Modern World by Steven Hoelscher

This essay is derived from a longer article to be published in Rundbrief Fotografie. We thank the editor for permission to reprint here.

Want to read more about Magnum Photos and photojournalism? Click here.

Head Photo: National Guard Soldiers escort Freedom Riders along their ride from Montgomery to Jackson, Mississippi. Montgomery, Alabama, 1961, ©Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

All photos: Courtesy of the Harry Ransom Center with permission from Magnum Photos for any promotional work associated with Reading Magnum.

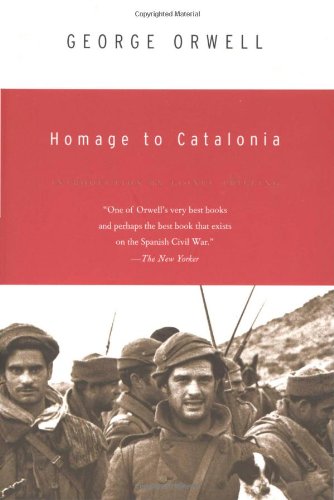

The book is Orwell’s personal narrative of his time spent fighting in trenches and behind barricades while slowly gaining an understanding of the politics that lay beneath the conflict. The book is not only a fascinating glimpse into a unique epoch but a fine example of Orwell’s writing style and personal life. Orwell, after all, has become a historical figure.

The book is Orwell’s personal narrative of his time spent fighting in trenches and behind barricades while slowly gaining an understanding of the politics that lay beneath the conflict. The book is not only a fascinating glimpse into a unique epoch but a fine example of Orwell’s writing style and personal life. Orwell, after all, has become a historical figure.