When the Soviets launched their campaign, known as the hujum, against the veil in Uzbekistan in 1927, their goal was not just to liberate women. Without a class framework or a working class to build socialism in Uzbekistan, Soviet activists instead attempted to transform society through the liberation of women. Northrop argues that a woman’s behavior and dress, expressed namely through the veil, came to symbolize all social values and, as such, became a battleground between Uzbek national identity and the socialist project. According to Northrop, the battle over the veil thus came to represent a process of mutual self-definition.

When the Soviets launched their campaign, known as the hujum, against the veil in Uzbekistan in 1927, their goal was not just to liberate women. Without a class framework or a working class to build socialism in Uzbekistan, Soviet activists instead attempted to transform society through the liberation of women. Northrop argues that a woman’s behavior and dress, expressed namely through the veil, came to symbolize all social values and, as such, became a battleground between Uzbek national identity and the socialist project. According to Northrop, the battle over the veil thus came to represent a process of mutual self-definition.

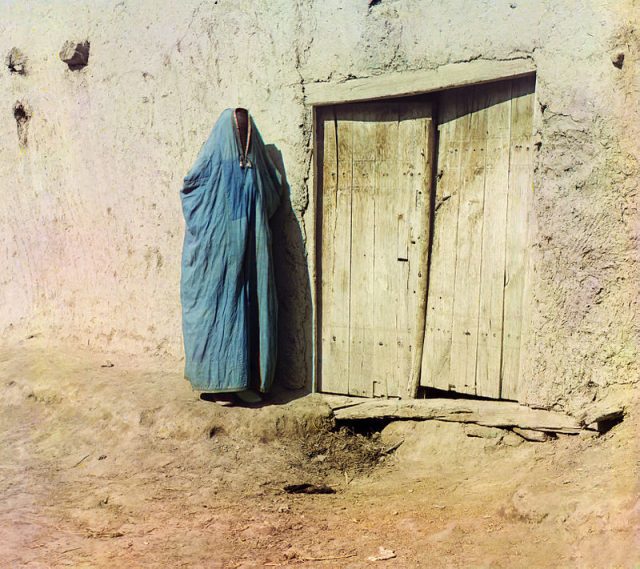

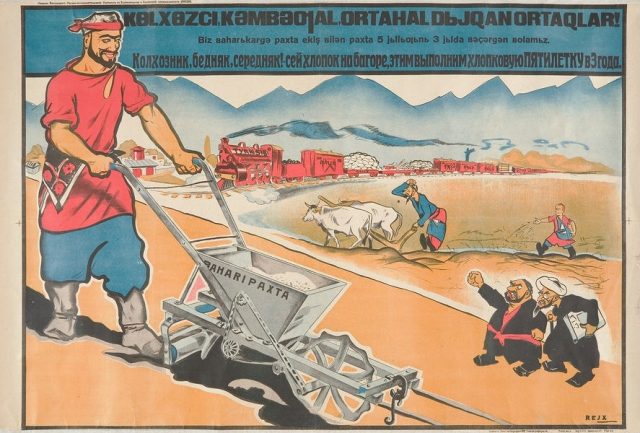

Northrop’s main aim is to explain the unfolding of Soviet policy in Central Asia through the lens of gender relations and policy. Rooted in a colonial studies framework, Northrop argues that the campaign to unveil women began only after the isolation of Muslim clerics and landowners as class enemies failed to win the rest of the population to their side. Only then did Soviet activists initiate the “liberation” of women as the means to build socialism, through bringing profound changes to Uzbek society, culture, and everyday life. In 1927, these Soviet activists launched a campaign, or hujum, to liberate Muslim women from seclusion and oppression through mass unveiling, which they hoped would dismantle the traditional patriarchal structure of everyday life.

Woman wearing a traditional paranja in Samarkand (present-day Uzbekistan) circa 1910 (via Wikimedia Commons).

Northrop highlights the limits to Soviet power through a thought-provoking consideration of Uzbek responses to this new drive to unveil women. For the most part Uzbeks resisted Soviet policies simply by non-compliance. Others learned to work the system or subvert Soviet language and logic, but wearing the veil became the primary symbolic assertion of anti-Soviet sentiment. Apart from expressing anti-Soviet sentiment, however, exactly how opposition to the hujum fostered Uzbek identity beyond preserving traditional cultural and societal structures remains an elusive aspect of the book.

Northrop’s use of gender as an analytical framework is arguably the most valuable contribution of Veiled Empire. He masterfully considers the way the Uzbek woman’s body became conflated with a social purpose by both Uzbeks and Soviet policy makers, as women’s behavior and dress came to represent practices in everyday life and social values in communities and in the nation as a whole. Northrop shows that unveiling did not necessarily spell out “liberation” for Uzbek women because western notions of feminism, gender, and patriarchy are not universal. For example, veils were not necessarily associated with oppression in Uzbek society, evident in the fact that the Uzbek Zhenotdel (Women’s Bureau) did not make it a chief concern before 1926. Northrop’s consideration of gender relations from both a Soviet and an Uzbek perspective thus allows him to understand the complexity of underlying tensions during the hujum and connect the gender project to broader Soviet goals. It is unfortunate, however, that women’s experiences are largely absent from this account, due to a lack of sources, as their voices would help further illuminate these tensions and complexities.

Soviet propaganda poster urging Uzbek peasants to speed up cotton production. Islamic clerics are depicted disparagingly (via Wikimedia Commons).

Overall, Veiled Empire is an admirable work that illuminates the limits of Soviet power in Central Asia. Using gender as an analytical framework, Northrop highlights how the Soviets attempted to use the “liberation” of women as a means to meeting a broader goal of building socialism. On both the Soviet and Uzbek sides, the veil was made to represent an entire identity and was conflated with social utility. As such, Northrop highlights the ways “oppression” and “liberation” are not as straightforward as Soviet activists hoped they were.

![]()

You may also like:

Janine Jones reviews The Politics of the Veil, by Joan Wallach Scott and Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject by Saba Mahmood (2004).

Christopher Rose recalls Exploring the Silk Route in Uzbekistan.

![]()