By Brian Levack

Ever since the beginning of Christianity, the belief has existed that demons can enter the bodies of human beings and take control of their physical movements and mental faculties. Those people who reportedly have experienced such possessions, known as demoniacs, have displayed a wide variety of symptoms, including convulsions, rigidity of the limbs, and vomiting extraneous substances such as pins, nails, or stones. A few demoniacs were reported to have levitated. The possessed also reportedly conversed in languages of which they had no previous knowledge, spoke in deep voices that were different from their normal voices, displayed contempt for sacred objects, uttered blasphemies, went into trances, and foresaw the future. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the period of the Reformation, there was an “epidemic” of such possessions. Some of them were group possessions in which many people in small communities, such as convents and orphanages, displayed the same symptoms.

The challenge for historians is to make sense of this bizarre, pathological behavior. For most people living at the time, the afflictions experienced by demoniacs made perfect sense, since they believed that the Devil or one of his demonic subordinates had the power to enter people’s bodies against their will. Others, however, including many who believed in the existence of the Devil, posed alternative rational, natural explanations why these demoniacs acted the way they did. The most common “rational” explanation of what was “really happening” to the possessed was that they were either physically or mentally ill: either epileptics or victims of hysteria. In the view of most modern psychiatrists, demoniacs were simply experiencing some sort of disorder, such as dissociative identity disorder, commonly known as multiple personality syndrome. Another rational explanation was that demoniacs were faking their possessions so that they could engage in anti-social or anti-religious behavior without being prosecuted for a criminal or religious offense. They were able to do so because demoniacs were not legally or morally responsible for anything done or said while possessed, since the Devil was believed to have forced them to speak or act.

The only human being who could be held responsible for causing a possession was a witch who commanded the Devil to enter the body of another person. Many of the cases of witchcraft in the Reformation era began when demoniacs accused a person of causing their possession by means of witchcraft.

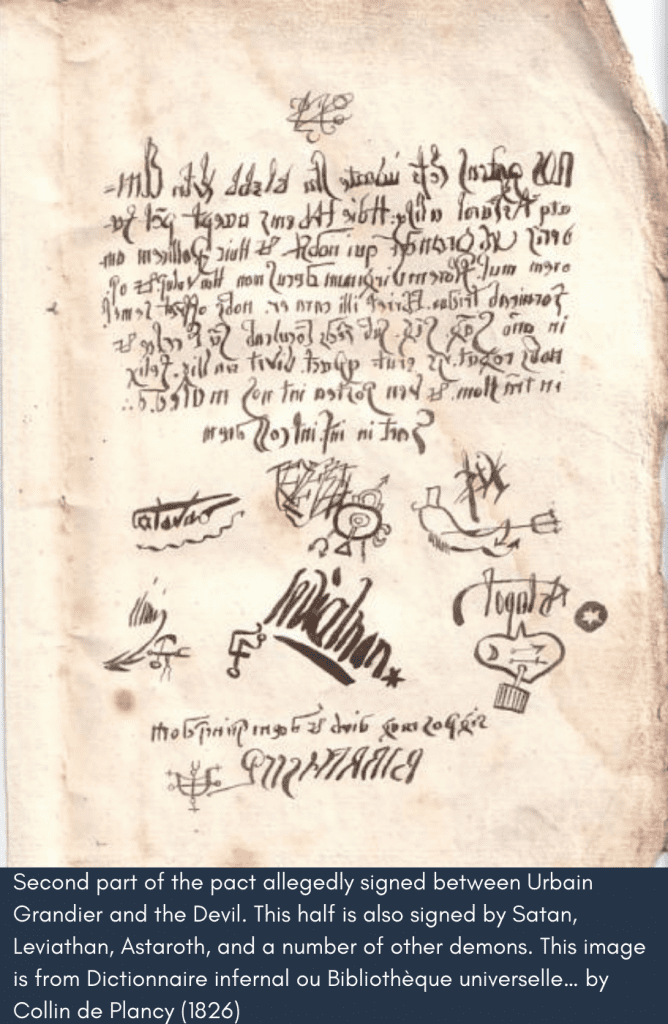

Medical and other rational explanations of possession can contribute to an explanation of some possession cases, but they cannot account for all the symptoms displayed by demoniacs, especially those that reflected the religious views of the possessed. The key to understanding this phenomenon is to recognize that all demoniacs, either consciously or unconsciously, were following scripts that were encoded in their religious cultures. They were, in a sense, performers in a sacred drama. Demoniacs learned their scripts from observing other demoniacs or by reading the many published narratives of other possessions or by hearing sermons that related the details of famous possessions. Some of them acquired knowledge of possession scripts from their exorcists, who suggested things they might say or do while in the state of possession. Nuns in convents often imitated the symptoms of those who had already exhibited some of the signs of possession. In the most famous case of possession in seventeenth-century Europe, the nuns in a convent at Loudun in France, after witnessing the convulsions and sexual gestures of the Mother Superior, Jeanne des Anges, began to act in a similar manner. This group possession resulted in a mass exorcism, and it led to the execution of a parish priest, Urbain Grandier, in 1634 for having caused their possession by means of witchcraft.

The scripts followed by Catholic and Protestant demoniacs and by the exorcists who tried to dispossess them were different. Catholic demoniacs, for example, were repulsed by the sacraments, especially the Eucharist, which is the most distinctive feature of Catholic sacramental culture. Protestant demoniacs on the other hand often reacted violently to hearing or even seeing a copy of the Bible, which was the foundation of Protestant faith. Catholic exorcists appealed to the Virgin Mary and other saints to help them expel the invasive demons, whereas Protestants, who emphasized the sovereignty of God to whom individuals prayed directly, left that task to God alone. Catholic demoniacs, especially young Catholic women, tended to display unconventional or prohibited sexual behavior during their possessions, whereas Protestants, who did not believe in a hierarchy of moral offenses, exhibited a wide range of sinful activities, including disobedience and playing cards. In more general terms, Catholics emphasized the innocence of demoniacs, whereas Protestants stressed their sinfulness. This helps explain why there were far more Catholic than Protestant demoniacs, since admitting one’s guilt might lead to the assumption that they were predestined to eternal damnation.

The incidence of demonic possession declined notably in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but in the late twentieth century the number of reported cases increased dramatically. Celebrity exorcists in Italy, Poland, and Latin America have been in large part responsible for this increase. The demoniacs who have flocked to these exorcists have not, however, displayed many of the classic symptoms of possession. They have not, for example vomited pins or blasphemed. In most cases they were plagued by medical or psychological problems and have sought the assistance of exorcists who promised to cure them. The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries remain “The Golden Age” of demonic possession.

James Sharpe, The Bewitching of Anne Gunter, (1999).

An entertaining study of one of the most remarkable cases of possession and witchcraft in early seventeenth-century England.

Carol F. Karlsen, The Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England, (1998).

A study of witchcraft in New England that focuses on the relationship between witchcraft and possession, especially at Salem, Massachusetts in 1692.

Giovanni Levi, Inheriting Power: The Story of an Exorcist, (1988).

The story of an uneducated priest in northern Italy who performed hundred of exorcisms as a strategy to bolster his authority as a priest.

Matt Baglio, The Rite: The Making of a Modern Exorcist, (2009).

The true story of the training of an American priest as an exorcist at the Vatican in the late twentieth century.

You may also enjoy:

Films about Possession & Exorcism

Photo Credits:

Via Wikimedia Commons:

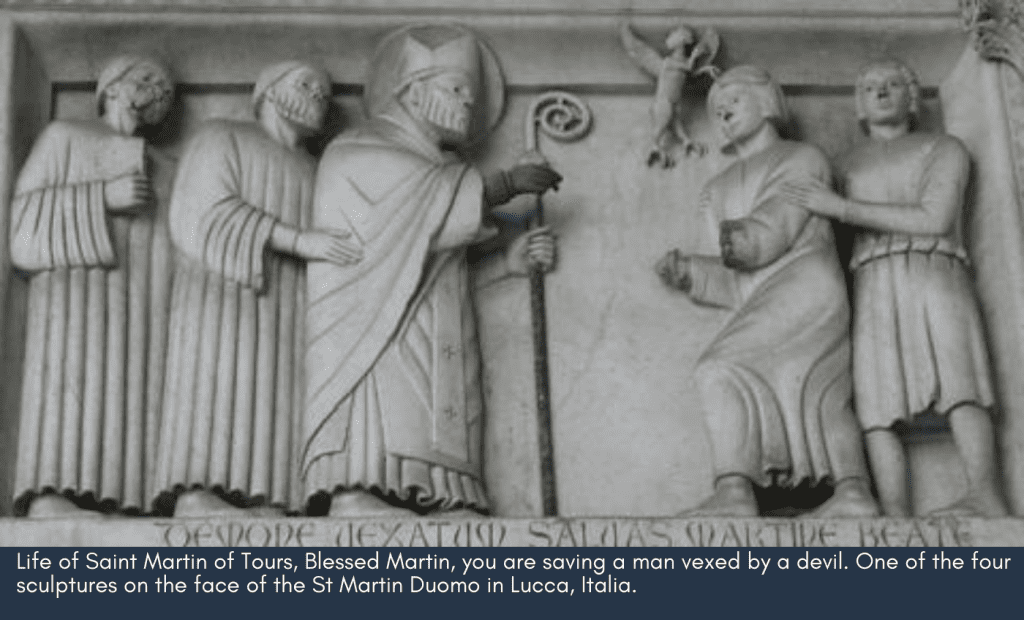

Life of Saint Martin of Tours, Blessed Martin, you are saving a man vexed by a devil. One of the four sculptures on the face of the St Martin Duomo in Lucca, Italia.

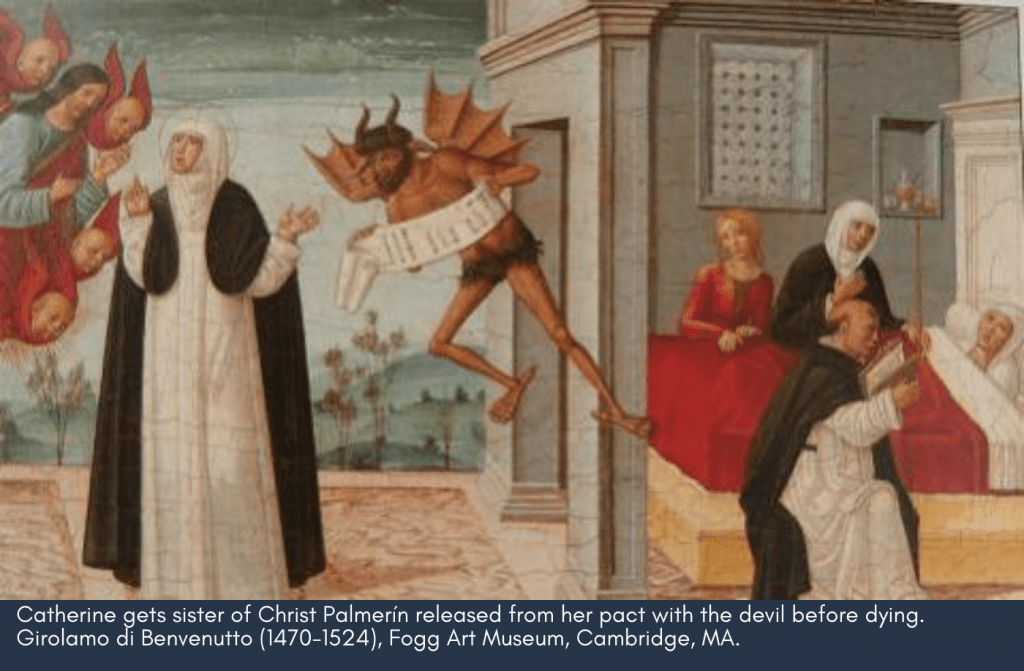

Catherine gets sister of Christ Palmerín released from her pact with the devil before dying. Girolamo di Benvenutto (1470-1524), Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, MA.

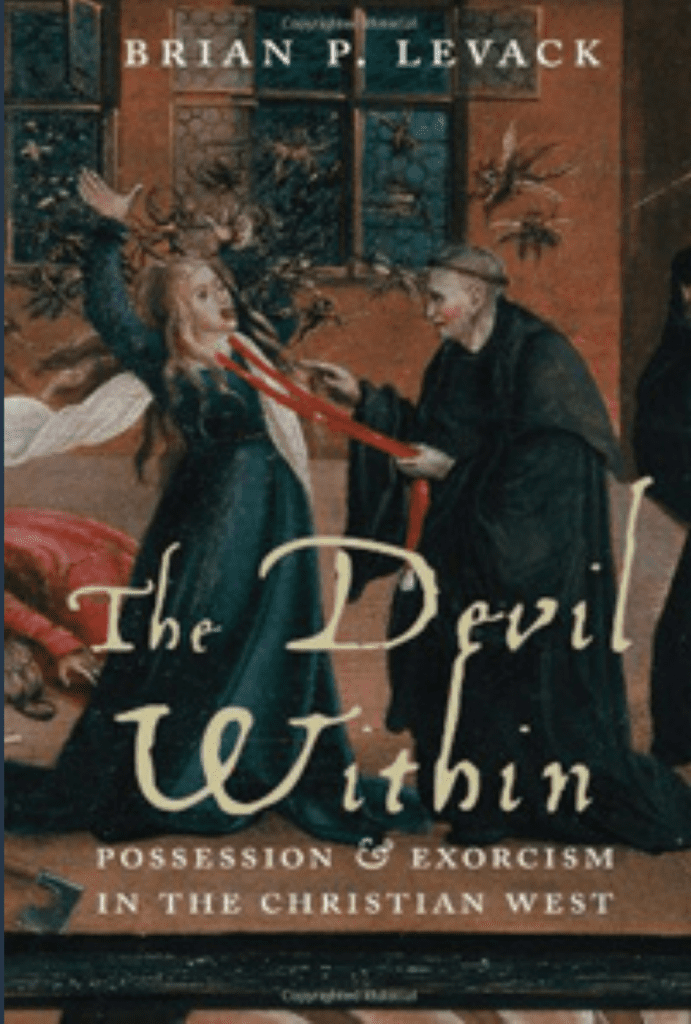

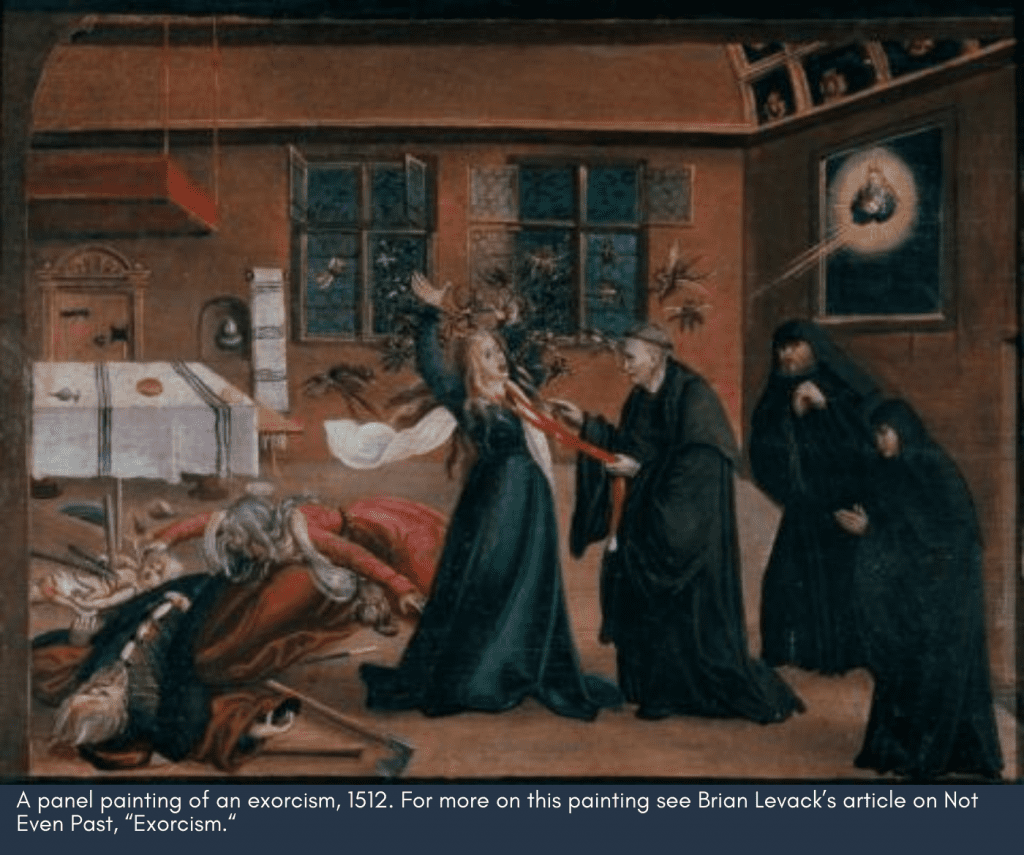

San Francisco de Borja y el moribundo impenitente. Capilla de San Francisco de Borja de la Catedral de Valencia, by Francisco Goya, 1788. Painting reproduced with permission from the Universalmuseum Joanneum: A panel painting of an exorcism, 1512. For more on this painting see Brian Levack’s article on Not Even Past, “Exorcism.”

Dreyer, who is best known for

Dreyer, who is best known for