In this history of popular religion and spirituality, Matthew Hedstrom argues that books and book culture were integral for the rise of liberal religion in the twentieth century. After World War I, a modernizing book business and an emerging religious liberalism expanded the spiritual horizons of many middle-class Americans. The new spiritual forms of twentieth-century liberalism incorporated psychology, mysticism, and (to a lesser extent) positive thinking in their works. Hedstrom, like sociologist Christian Smith, believes that liberal religion achieved a stunning cultural victory after World War II.

In this history of popular religion and spirituality, Matthew Hedstrom argues that books and book culture were integral for the rise of liberal religion in the twentieth century. After World War I, a modernizing book business and an emerging religious liberalism expanded the spiritual horizons of many middle-class Americans. The new spiritual forms of twentieth-century liberalism incorporated psychology, mysticism, and (to a lesser extent) positive thinking in their works. Hedstrom, like sociologist Christian Smith, believes that liberal religion achieved a stunning cultural victory after World War II.

Two key developments led to the rise of liberal religion: the embrace of the marketplace and the creation of middlebrow reading culture. In the 1920s, liberal Protestants turned to the marketplace, but on their own terms. They wanted people to read right. Middlebrow reading required that one read earnestly, intensely, and with purpose. Many liberal Protestants thought that this manner of reading would improve people. Middlebrow reading norms also required individual autonomy and expertise. Religious and cultural leaders carefully shepherded readers by offering comfortable — but limited — freedom to act as guided consumers. In other words, religious leaders still hoped to shape the purchases that laymen and laywomen made and the book industry complied.

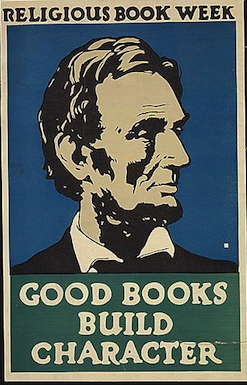

The First World War destroyed the faith Americans had in simple notions of progress. In response to this crisis, liberal Protestant leaders, executives of the American publishing industry, and other cultural figures collaborated on a series of new initiatives to promote the buying and reading of religious books. These initiatives included the Religious Book Week, the Religious Book Club, and the Religious Books Round Table of the American Library Association. Major publishing houses, like Harper’s and Macmillan, established religious departments for the first time.

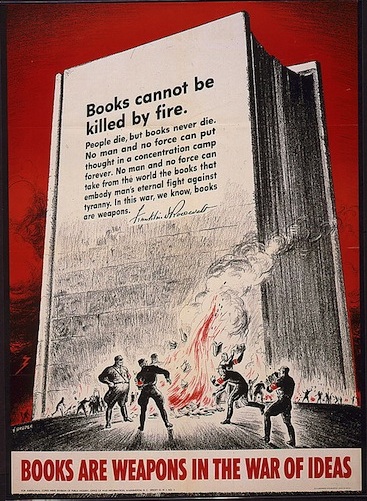

In the interwar years, religious reading became a national concern as the United States faced the threat of fascism. Religious groups like the Council on Books in Wartime and the Religious Book Week campaign of the National Conference of Christians and Jews (NCCJ) promoted reading. Hedstrom shows the widespread appeal of the Council’s slogan, “Books as Weapons in the War of Ideas.” The Second World War, for these groups, was not only an ideological battle, it was also a spiritual struggle for the soul.

After the war, Americans continued to turn to books for spiritual guidance. And the increasing belief that the United States was a Judeo-Christian nation formed the foundation of what Hedstrom calls “spiritual cosmopolitanism.” Letters to Rabbi Joshua Loth Liebman and Harry Emerson Fosdick, two of the most popular post-World War II authors of liberal religion, display Americans’ newfound eagerness to read religious and spiritual works from authors of other faiths. These letters also provide keen insight into who was reading spiritual books and why and how they were reading them. Many Americans were religious, even if they were not attending church on Sundays. Readers of middlebrow religious culture were trying to grapple with religious questions about the Second World War, morality, and spirituality. Fosdick and Liebman helped them find answers.

The Rise of Liberal Religion is revisionist history in the best possible sense. By emphasizing “lived religion,” or the spaces where religion is practiced and faith is formed, Hedstrom shows that the numerical decline of mainline Protestant churches and churchgoers matters less than previous historians insisted. In addition, Hedstrom challenges the master narrative that conservative Christianity dominated the post-World War II religious landscape. Despite this, readers might find a few shortcomings. First, Hedstrom makes too many sweeping declarations about liberal religion after the 1950s. For example, he points to Americans’ incorporation of yoga as a form of spiritual cosmopolitanism, but it is not clear that liberal religion in the U.S. made a conscious effort to incorporate yoga into its practice. More important, Hedstrom provides little evidence about the lived religious experiences of women, African Americans, and Native Americans. He asserts that middlebrow reading provided women agency, but the evidence from women themselves is somewhat thin. By emphasizing the vitality of liberal religious experience, Hedstrom has set a new agenda for the cultural history of U.S. religion, but that cultural history will have to incorporate more of the population of the faithful for it to have a real impact.

Matthew Hedstrom, The Rise of Liberal Religion: Book Culture and American Spirituality in the Twentieth Century (Oxford University Press, 2013)

You may also like these reviews by Christopher Babits:

Age of Fracture, by Daniel T. Rodgers (2011)

And Robert Abzug’s discussion of William James’s The Varieties of Religious Experience.