By Michael J. Kramer

History & American Studies, Northwestern University

Dramaturg, The Seldoms

“I can see them now, Clio and Terpsichore…I can feel them spinning, lurching, sidling and smashing up against one another, laughing knowingly as they wipe the sweat of foreheads and from the skin between lips and nose; in a standoff, carefully calculating each other’s weight and flexibility, careening toward one another, rolling as one body and then falling apart, only to circle around for a fast-paced repartee, trading impersonations…. This duet rejuvenates itself endlessly. It has an insatiable appetite for motion.” Susan Leigh Foster, “Choreographing History”

“It is all here: the story of our time with the bark off…” Lyndon Johnson at the dedication of the LBJ Presidential Library, 1971

In the contemporary dance theater work Power Goes, which arrives at McCullough Theatre on the campus of the University of Texas on September 16th and 18th, courtesy of Texas Performing Arts, the Briscoe Center for American History, and the LBJ Presidential Library, the Chicago-based dance ensemble, The Seldoms, propose that we can dance our way deeply into the historical past. So too, they stake out the claim that the past, arriving through dance performance, has important work to do in the present. Presiding over Power Goes is the figure of Lyndon Baines Johnson, who serves as a guiding spirit for an exploration of physicality, power, and social change. Using videography, spoken text, distinctive lighting, sound design, and, most of all, dynamic, innovative movement, The Seldoms ask audiences to join them in drawing upon LBJ’s legacy and his times to consider what power is exactly and how, as the work’s title suggests, it goes.

Power Goes relies significantly upon archival sources to pursue this investigation. In this sense, it is a work of public history, except that it adds the body, movement, and performance to text, image, and sound as means for discovering and communicating its findings. History is all over this piece. Even the title of Power Goes comes from an oft-cited saying coined by Johnson, “Power is where power goes,” meaning that he could exercise political influence and control in any office he occupied. The Seldoms take this line and run—or better said (of course) dance—with it. Power Goes refers to everything from Johnson’s childhood in Texas Hill Country to his political prowess as an intensely physical leader to the broader civil rights and social movements for equality in the 1960s to Johnson’s tragic political demise after his decision to escalate US military involvement in the Vietnam War. But this is no biography of Johnson, and it is certainly not hagiographical. Power Goes is certainly not history in the conventional sense. By presenting history in dance, it asks us to reconsider what public history is and what it can be.

Power Goes relies significantly upon archival sources to pursue this investigation. In this sense, it is a work of public history, except that it adds the body, movement, and performance to text, image, and sound as means for discovering and communicating its findings. History is all over this piece. Even the title of Power Goes comes from an oft-cited saying coined by Johnson, “Power is where power goes,” meaning that he could exercise political influence and control in any office he occupied. The Seldoms take this line and run—or better said (of course) dance—with it. Power Goes refers to everything from Johnson’s childhood in Texas Hill Country to his political prowess as an intensely physical leader to the broader civil rights and social movements for equality in the 1960s to Johnson’s tragic political demise after his decision to escalate US military involvement in the Vietnam War. But this is no biography of Johnson, and it is certainly not hagiographical. Power Goes is certainly not history in the conventional sense. By presenting history in dance, it asks us to reconsider what public history is and what it can be.

At a time when scholarly historians are working to make academic history more accessible to broader audiences, looking to other fields that confront similar issues might be stimulating. Contemporary dance faces oddly parallel issues to academic history. Both have typically been made for smaller, specialized audiences even though both history and dance are important activities for a far broader swath of the population. To witness how The Seldoms use innovative choreographic tactics, cross-disciplinary collaboration, sustained studio practice, ongoing self-scrutiny, continued public dialogue, and, most importantly, the body itself, as avenues to deeper interpretive understanding of both the past and the present (and perhaps as a way to imagine the future) is to consider new areas of possibility for public history as well.

At a time when scholarly historians are working to make academic history more accessible to broader audiences, looking to other fields that confront similar issues might be stimulating. Contemporary dance faces oddly parallel issues to academic history. Both have typically been made for smaller, specialized audiences even though both history and dance are important activities for a far broader swath of the population. To witness how The Seldoms use innovative choreographic tactics, cross-disciplinary collaboration, sustained studio practice, ongoing self-scrutiny, continued public dialogue, and, most importantly, the body itself, as avenues to deeper interpretive understanding of both the past and the present (and perhaps as a way to imagine the future) is to consider new areas of possibility for public history as well.

The choice of Lyndon Johnson as subject matter brings history and dance together quite directly. Johnson, as a character, is no stranger to the stage. Bryan Cranston, of television series Breaking Bad fame, took on the role of LBJ in the recent Broadway play All the Way (soon to be an HBO biopic), which tells the story of Johnson’s efforts to push through civil rights legislation in the aftermath of his landslide Presidential victory in 1964. Johnson also turns up as an opponent of civil rights legislation on screen in the recent film Selma, directed by Ava DuVernay. In the 1960s themselves, LBJ was even placed in the villainous position of Macbeth in Barbara Garson’s satirical and angry radical theater work MacBird!

In Power Goes, however, he is more like Banquo’s ghost. He haunts the piece, looms over it, even gives it the infamous “Johnson treatment” that he was renowned for when he leaned his six foot four frame over allies and adversaries alike to get them in line for his legislation. The Seldoms are less interested in retelling Johnson’s story than allowing it to work its way into the present moment. This is not historical reenactment or naturalistic dramatic realism. Instead, The Seldoms demand that audiences enter into a version of history that is lively, weird, uneven, palpable. No one member of The Seldoms alone plays the role of LBJ, for instance, or remains in the position of any other specific historical person consistently. Stable identities give way to the porous flow of power as it courses through the bodies of the dancers.

In Power Goes, however, he is more like Banquo’s ghost. He haunts the piece, looms over it, even gives it the infamous “Johnson treatment” that he was renowned for when he leaned his six foot four frame over allies and adversaries alike to get them in line for his legislation. The Seldoms are less interested in retelling Johnson’s story than allowing it to work its way into the present moment. This is not historical reenactment or naturalistic dramatic realism. Instead, The Seldoms demand that audiences enter into a version of history that is lively, weird, uneven, palpable. No one member of The Seldoms alone plays the role of LBJ, for instance, or remains in the position of any other specific historical person consistently. Stable identities give way to the porous flow of power as it courses through the bodies of the dancers.

Similarly, The Seldoms do not stick to one historical time period or level of historical action. Past and present blur. Official and informal intermix. Access to haircut stylists and self-help audio tapes become issues of power relations right alongside pressing issues of national import. The micropolitics of everyday life interweave with public spectacles of political theater. History jumps around, we cut between and across time periods, and between fantastical interactions (a conversation between LBJ and Obama) and realpolitik (Johnson intimidating a segregationist business owner into hiring African-Americans).

History pulsates here. Sometimes it pummels bodies with trauma. At other times, we witness the power of bodies that are massed in stillness and endurance. Sometimes these bodies are vulgar. At other times, they are quite tender and vulnerable. History disappears into the bodies onstage, but the dancers also become historical vessels, bringing the past into the present moment. Power Goes does not offer a “history of the body,” as historians have done in the past decades; rather, it presents history through the body. LBJ’s physicality is the beginning of a much larger inquiry into how history surfaces through skin and bones, exertion of muscle and tangle of nerve.

But what a perfect starting point LBJ is. Whether it be something as crass as taking aides into his bathroom while he urinated or something more kindly such as wrapping his arms around friends to show his fondness for them, LBJ’s physicality was crucial to his politics. He was often awful on television, but a master of face-to-face glad-handing. Johnson’s body was, in some sense, his politics. Presidential bodies are significant anyway, beyond LBJ alone. As Ernst Kantorowicz wrote of Medieval political theology in his classic study The King’s Two Bodies, and as Michael Rogin translated into the American context, leader’s bodies have always borne a close relationship to the body politic. We think about the larger nation-state, sometimes, through linking the literal body of a leader to the metaphorical social body. The President is not called the head of state for nothing.

But what a perfect starting point LBJ is. Whether it be something as crass as taking aides into his bathroom while he urinated or something more kindly such as wrapping his arms around friends to show his fondness for them, LBJ’s physicality was crucial to his politics. He was often awful on television, but a master of face-to-face glad-handing. Johnson’s body was, in some sense, his politics. Presidential bodies are significant anyway, beyond LBJ alone. As Ernst Kantorowicz wrote of Medieval political theology in his classic study The King’s Two Bodies, and as Michael Rogin translated into the American context, leader’s bodies have always borne a close relationship to the body politic. We think about the larger nation-state, sometimes, through linking the literal body of a leader to the metaphorical social body. The President is not called the head of state for nothing.

A leader’s body, however, is not the only one that matters, particularly in a democracy. When The Seldoms pivot from LBJ to other people from the 1960s—civil rights protesters, antiwar demonstrators, everyday citizens, fearful political adversaries, potential political allies—the range of the dance piece’s exploration of physicality and power grows dramatically as well. Scales and sizes, individual bodies and masses of bodies, stillness and motion, duration and action, all contrast with each other. Varying tones and intensities of assertion, rejection, conflict, and concordance register. The Seldoms loosen history from its moorings, embodying its implications and giving them a physical presence. Power Goes enlarges historical awareness through embodiment. The company even hold a workshop, “Bodies on the Gears,” in which participants explore the historical gestures with their own physical being; these workshop attendees then join in the performance itself.

The oscillations in Power Goes between bodies then and now—the way that The Seldoms move from the 1960s and the present, the archives to the stage, a straightforward retelling of the past to something far more adventurous, even delirious—also raise questions about history and memory. Aligning physical exploration with evidence, argument, and interpretation, The Seldoms create a deeply intellectual investigation that is also a sensorial séance. Ghosts from the past shoot through the bodies of The Seldoms into the present moment, but they never settle into place. Instead they mutate and change as their stances and positions get reworked, abstracted, reconfigured, re-physicalized, redistributed, redirected, and recontextualized by the dancers. Memory itself becomes alive, suddenly happening now, a tailwind that must be negotiated in the moment, a highly charged experience in which structures of power grow fluid and unruly.

The oscillations in Power Goes between bodies then and now—the way that The Seldoms move from the 1960s and the present, the archives to the stage, a straightforward retelling of the past to something far more adventurous, even delirious—also raise questions about history and memory. Aligning physical exploration with evidence, argument, and interpretation, The Seldoms create a deeply intellectual investigation that is also a sensorial séance. Ghosts from the past shoot through the bodies of The Seldoms into the present moment, but they never settle into place. Instead they mutate and change as their stances and positions get reworked, abstracted, reconfigured, re-physicalized, redistributed, redirected, and recontextualized by the dancers. Memory itself becomes alive, suddenly happening now, a tailwind that must be negotiated in the moment, a highly charged experience in which structures of power grow fluid and unruly.

The Seldoms have created a piece that allows audiences to experience history, with a thrilling combination of visceral immediacy and meditative contemplation. LBJ oversees this affair, and protesters and others from the 1960s show up to play their parts, but it is the relationship between history and power, between what things persist and how things change, between what gets remembered and how we remember it, that ultimately takes center stage in Power Goes. As a kind of epic duet choreographed between dance and history, Terpsichore and Clio, this is a version of public history that has got serious moves.

Watch a one minute trailer or the entire piece (80 minutes).

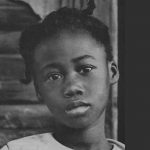

All photographs by William Frederking

Cited Sources:

Susan Leigh Foster, “Choreographing History” in Choreographing History, ed. Susan Foster (1995).

Lyndon Johnson, Dedication of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum, May 22, 1971, http://www.lbjlibrary.org/page/library-museum.

Ernst Kantorowicz, The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology (1957).

Michael Paul Rogin, “The King’s Two Bodies: Lincoln, Wilson, Nixon, and Presidential Self-Sacrifice,” in “Ronald Reagan,” The Movie, and Other Episodes in Political Demonology (1987).