The forces that created the Cuban Revolution often get lost in polarizing debates about Castro’s Cuba. Two very different films highlight the changes that ripped through Cuban society in the 1950s and early 1960s and created the Cuban Revolution. The first is Tomás Gutierrez Alea’s Memories of Underdevelopment (Memorias del subdesarrollo) released in Cuba in 1968 and the second is Steven Soderbergh’s 2008 Hollywood biopic Che.

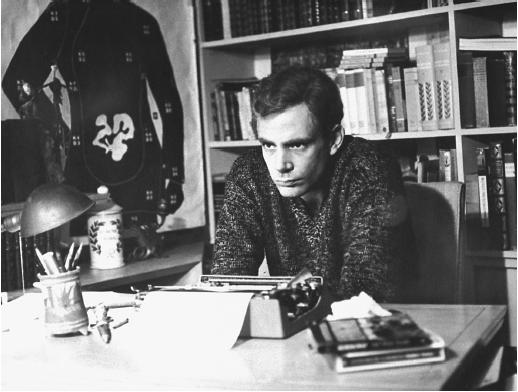

Memories of Underdevelopment, based on Edmundo Desnoes’s 1967 novel, is perhaps the best-known film in Gutiérrez’s long and productive career. The film dramatizes the forces rapidly transforming Cuban society in the early years of the Cuban Revolution through the eyes of Sergio (skillfully played by Sergio Corrieri), a member of the old Cuban elite that was overthrown by the revolution. Sergio is a frustrated intellectual who, unlike his elite and middle-class contemporaries, decides to stay in Cuba rather than flee to the United States. In Gutierrez’s masterful depiction of Sergio, made evident in the scenes of the coat and tie wearing Sergio aimlessly wandering the streets of Havana, one sees the rapid decline of an older civilian model of Cuban masculinity, one that was predicated on affluence, consumption, and affiliation with the United States, as well as sexual predatory “machismo.” Sergio is in many ways a prototypical “ladies man” who manifests his own alienation by preying upon young women. Yet, Corrieri’s performance evokes sympathy for a character who is lost, yet, keenly aware of the changes that are happening all around him.

Memories of Underdevelopment, based on Edmundo Desnoes’s 1967 novel, is perhaps the best-known film in Gutiérrez’s long and productive career. The film dramatizes the forces rapidly transforming Cuban society in the early years of the Cuban Revolution through the eyes of Sergio (skillfully played by Sergio Corrieri), a member of the old Cuban elite that was overthrown by the revolution. Sergio is a frustrated intellectual who, unlike his elite and middle-class contemporaries, decides to stay in Cuba rather than flee to the United States. In Gutierrez’s masterful depiction of Sergio, made evident in the scenes of the coat and tie wearing Sergio aimlessly wandering the streets of Havana, one sees the rapid decline of an older civilian model of Cuban masculinity, one that was predicated on affluence, consumption, and affiliation with the United States, as well as sexual predatory “machismo.” Sergio is in many ways a prototypical “ladies man” who manifests his own alienation by preying upon young women. Yet, Corrieri’s performance evokes sympathy for a character who is lost, yet, keenly aware of the changes that are happening all around him.

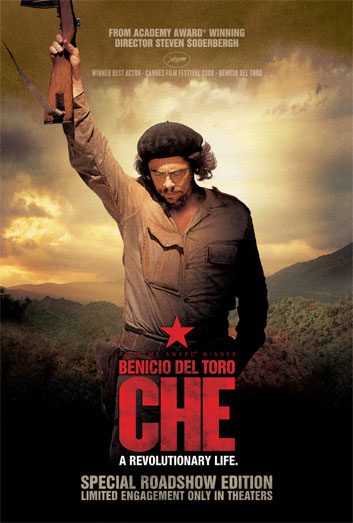

Steven Soderbergh’s Che can be read as a completely different meditation on Cuban manhood. While ostensibly about Ernesto “Che” Guevara, one of the revolution’s key leaders, the film also explores the emergence of the “new man” of 1950s-60s Cuba, the new socialist individual that Guevara hoped to create in the Cuban Revolution. Soderbergh’s lengthy 4-hour movie is divided into two parts: the first portrays Che’s involvement in the guerrilla war against Cuba ruler Fulgencio Batista and the second explores his ill-fated guerrilla campaign in 1967 in Bolivia. Unlike Sergio, who relishes his class privilege, Che (brilliantly played by Benicio del Toro) is a selfless doctor who rejects the benefits of bourgeois existence to devote his entire life to becoming a career revolutionary motivated by “profound feelings of love,” as Che himself put it. Soderbergh’s depictions of Che’s encounters with Cuban peasants, his tending to wounded soldiers, and his fearlessness as a commanding officer in the guerrilla war underscore the model of revolutionary masculinity celebrated by the triumphant Cuban Revolution. While many have criticized the film’s glossing over of Guevara’s involvement in the execution of counter-revolutionaries, viewers who do not give the film a chance will miss an opportunity to gain insights into the factors that explain the triumph of the Cuban Revolution.

Steven Soderbergh’s Che can be read as a completely different meditation on Cuban manhood. While ostensibly about Ernesto “Che” Guevara, one of the revolution’s key leaders, the film also explores the emergence of the “new man” of 1950s-60s Cuba, the new socialist individual that Guevara hoped to create in the Cuban Revolution. Soderbergh’s lengthy 4-hour movie is divided into two parts: the first portrays Che’s involvement in the guerrilla war against Cuba ruler Fulgencio Batista and the second explores his ill-fated guerrilla campaign in 1967 in Bolivia. Unlike Sergio, who relishes his class privilege, Che (brilliantly played by Benicio del Toro) is a selfless doctor who rejects the benefits of bourgeois existence to devote his entire life to becoming a career revolutionary motivated by “profound feelings of love,” as Che himself put it. Soderbergh’s depictions of Che’s encounters with Cuban peasants, his tending to wounded soldiers, and his fearlessness as a commanding officer in the guerrilla war underscore the model of revolutionary masculinity celebrated by the triumphant Cuban Revolution. While many have criticized the film’s glossing over of Guevara’s involvement in the execution of counter-revolutionaries, viewers who do not give the film a chance will miss an opportunity to gain insights into the factors that explain the triumph of the Cuban Revolution.

Both films satisfy the historian’s desire for accurate representations of the past. Memories gives us a taste of 1960s Cuba not only because it was made at the time, but also due to Gutiérrez’s skillful insertion of archival footage throughout the film. Soderbergh’s beautiful costume and set design, most evident in his attentiveness to the architecture of Cuban provincial towns in the decisive scenes of the Battle of Santa Clara, show that the film was based on solid research. One may quibble with each director’s political choices, but both films are brilliantly executed and provide valuable portrayals of monumental events in Cuban history. Each highlights, in different ways, competing models of Cuban male identity that are in tension with each other to this day.

Both films satisfy the historian’s desire for accurate representations of the past. Memories gives us a taste of 1960s Cuba not only because it was made at the time, but also due to Gutiérrez’s skillful insertion of archival footage throughout the film. Soderbergh’s beautiful costume and set design, most evident in his attentiveness to the architecture of Cuban provincial towns in the decisive scenes of the Battle of Santa Clara, show that the film was based on solid research. One may quibble with each director’s political choices, but both films are brilliantly executed and provide valuable portrayals of monumental events in Cuban history. Each highlights, in different ways, competing models of Cuban male identity that are in tension with each other to this day.