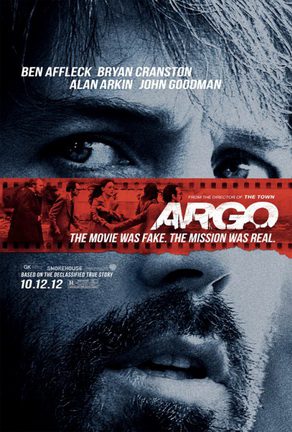

Argo, Ben Affleck’s latest film, is set against the backdrop of the 1979 Iranian Revolution. The audience is dropped abruptly into the action following a  semi-animated sequence that explains American involvement in Iran following the 1953 CIA-orchestrated coup that deposed democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh in favor of Shah Muhammad Reza Pahlavi.

semi-animated sequence that explains American involvement in Iran following the 1953 CIA-orchestrated coup that deposed democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh in favor of Shah Muhammad Reza Pahlavi.

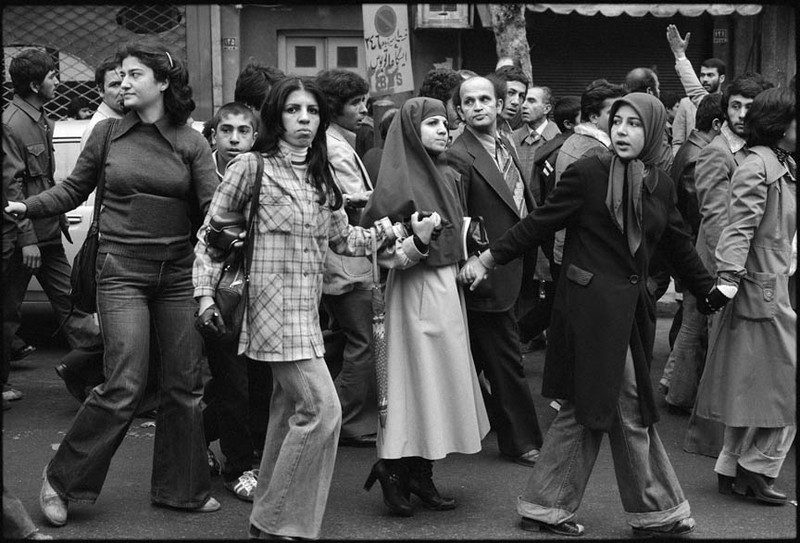

Viewers are given a quick rundown of the Shah’s lavish lifestyle and told that his attempts to Westernize Iran had met with resistance in this “traditionally Shi’ite country.” This, paired with the Shah’s increasing paranoia and authoritarianism, led to nationwide demonstrations and strikes over the latter half of 1978 that led to the Shah’s departure from the country on January 16, 1979.

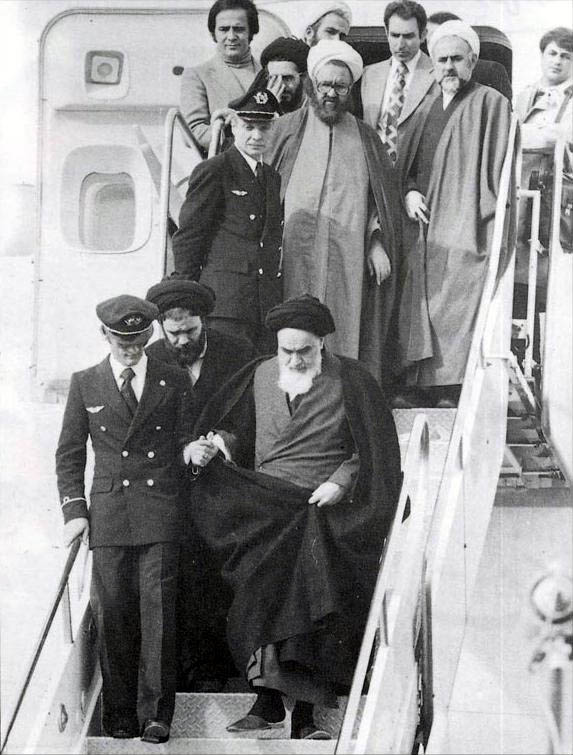

The introduction quickly moves through subsequent key events in the Revolution. Within two weeks, the revolution’s figurehead Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini had returned to Iran from exile in France, the Shah’s caretaker government had crumbled, and Iran descended into internal chaos as the various groups that had united under the common cause of deposing the Shah began to fight about what happened next and who would take control. Islamist forces loyal to Khomeini fought with secularists, Marxists, and a myriad of smaller groups from across the spectrum, all the while attempting to prevent a repeat of the 1953 coup by outside powers. In late October, the Shah, suffering from liver cancer, was admitted to the United States for treatment in New York. The Iranian government formally requested his extradition to stand trial in Iran for crimes against humanity; the Carter administration refused.

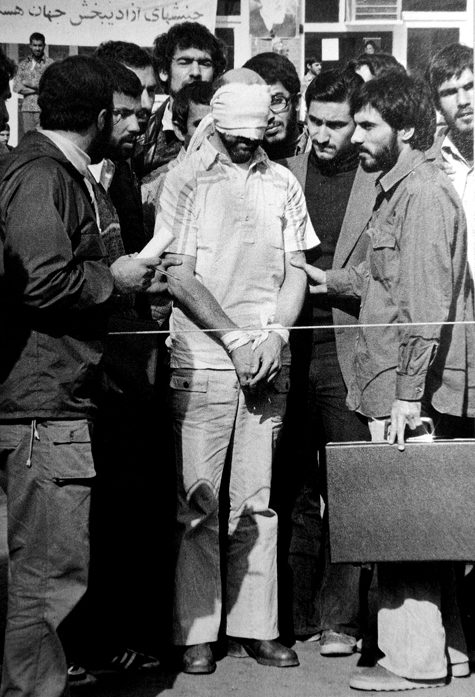

The film opens on November 4, 1979, the day that the American embassy was overrun

by a mob that took the embassy employees hostage. Initially, hopes were that Khomeini’s government would step in and release the hostages, as they had done previously, when the embassy was breached during the previous summer, but government officials instead sanctioned the hostage taking. The embassy employees would eventually be held in captivity for 444 days. The Iranian government agreed to release them on January 20, 1981—inauguration day in the U.S.—and held their plane on the tarmac at Tehran’s Mehrabad Airport until after Ronald Reagan had been sworn in as president. This was perceived as a final snub to outgoing president Jimmy Carter, who had stood beside the Shah in Tehran just three years earlier and proclaimed Iran “an island of stability in the Middle East.”

by a mob that took the embassy employees hostage. Initially, hopes were that Khomeini’s government would step in and release the hostages, as they had done previously, when the embassy was breached during the previous summer, but government officials instead sanctioned the hostage taking. The embassy employees would eventually be held in captivity for 444 days. The Iranian government agreed to release them on January 20, 1981—inauguration day in the U.S.—and held their plane on the tarmac at Tehran’s Mehrabad Airport until after Ronald Reagan had been sworn in as president. This was perceived as a final snub to outgoing president Jimmy Carter, who had stood beside the Shah in Tehran just three years earlier and proclaimed Iran “an island of stability in the Middle East.”

The story of the embassy takeover is practically script-ready for a Hollywood release. Argo focuses on a lesser-known—and recently declassified—subplot that, as the film’s advertising promises, nearly has to be seen to be believed.

The U.S. embassy occupied a city block in downtown Tehran. The main breach on the day of the takeover took place at the main entrance, where the chancery and administrative offices were located. The consular section was located in another section of the compound, which had a direct entrance to the street. Six members of the embassy staff were able to simply walk out the door before the consular section was breached, blending into normal traffic to escape. After several days of being harbored and then denied refuge in the British and New Zealand embassies, the American embassy employees were granted safe harbor in the residence of Canadian Ambassador Ken Taylor (played by Victor Garber).

The six employees were eventually able to flee Iran through a CIA-Canadian joint intelligence endeavor that involved posing the six as members of a film crew doing a location scout for a science fiction movie called Argo. The Canadian government issued them passports and CIA operative Tony Mendez (Affleck), working with operatives in the film industry, set up a cover office in Hollywood (staffed by an effervescent John Goodman and Alan Arkin, who provide much needed comic relief). Fake ads were placed in trade publications, and a lavish press event announcing the film was held, giving the cover story legitimacy. Mendez then flew to Tehran (in reality, Mendez was accompanied by an aide, not depicted in the film) and, to complete the disguise, escorted the staff on a location scout of the Tehran bazaar. Finally, in a business as usual-style, the crew went to the airport to board a Swissair flight to Zurich.

The film adds gratuitous tension to the escape scene, adding in a race against Iranian

intelligence officials who uncover the true identity of the “film crew” just as they prepare to board the plane, an unnecessary assault against a female gate agent who lacks the keys to reopen the gate once the plane is ready for departure, and an over the top chase scene involving revolutionary guards in late 1970s Chevrolets who manage to keep pace with a 747 thrusting down the runway for takeoff.

intelligence officials who uncover the true identity of the “film crew” just as they prepare to board the plane, an unnecessary assault against a female gate agent who lacks the keys to reopen the gate once the plane is ready for departure, and an over the top chase scene involving revolutionary guards in late 1970s Chevrolets who manage to keep pace with a 747 thrusting down the runway for takeoff.

Argo is the story of the Americans’ ordeal and their relatively miraculous escape—and in this it delivers. It is unfortunate, however, that the film presents these dramatic events against a simplified backdrop that diminishes the complexity of the Iranian political scene at the time.

What is missing is much of the backstory that explains why the Americans are in this predicament in the first place. With the current state of Iranian-US relations, contemporary audiences may not question the hostility of Iranians toward Americans as depicted in the film, but the filmmakers never quite explain that this was the very moment when the cozy relationship between the U.S. and a key ally turned incredibly sour.

More important, however, is the absence of any Iranian perspective. Only one Iranian

character in the film rises above the level of caricature, Sahar (Sheila Vand), the Taylor’s housekeeper. Her discomfort with the presence of the Americans in the household is eventually outweighed by her discomfort with the local komiteh—the ubiquitous neighborhood “committees” that sprang up after the Revolution to police the capital block by block—who become suspicious of the ambassador’s long-term “guests.” Sahar is eventually shown fleeing to neighboring Iraq, but it’s never quite explained why she needs to flee and what the repercussions of her remaining in Iran would have been. The scene is, instead, played tongue in cheek, meant to encourage audiences to roll their eyes at the thought of Iraq representing “safety.”

character in the film rises above the level of caricature, Sahar (Sheila Vand), the Taylor’s housekeeper. Her discomfort with the presence of the Americans in the household is eventually outweighed by her discomfort with the local komiteh—the ubiquitous neighborhood “committees” that sprang up after the Revolution to police the capital block by block—who become suspicious of the ambassador’s long-term “guests.” Sahar is eventually shown fleeing to neighboring Iraq, but it’s never quite explained why she needs to flee and what the repercussions of her remaining in Iran would have been. The scene is, instead, played tongue in cheek, meant to encourage audiences to roll their eyes at the thought of Iraq representing “safety.”

Argo also misses the opportunity to show that this is the period when many Iranians began to distrust the Revolutionary government. The 1979 Revolution brought together many disparate groups with different political agendas united by a common goal: deposing the hated Shah. Each group had wildly differing views of what should happen next: Khomeini’s forces, which were eventually successful, wanted to establish an Islamic Republic. Others wanted liberal democracy, still others a Marxist state allied with the Soviet Union, and some fringe groups wanted Iran to splinter along ethnic and linguistic lines. The backdrop of the events portrayed in Argo is the consolidation of Khomeini’s rule and the liquidation of its opponents.

There are brief glimpses of these tensions: during the Embassy siege, Cora Lijek (Clea DuVall) insists that the Iranians in the waiting room be allowed to leave first. “They’ll get in serious trouble if they’re caught applying for U.S. visas,” she explains, but the comment is lost among the turbulence of the moment and never revisited. That Iran is a bad place to be an American is reiterated repeatedly, but never quite explained.

Millions of Iranians fled the country during the revolution when they realized that what they initially took to the streets for—replacing the authoritarian rule of the Shah with a government that better represented them—would fail to bear fruit.

While it could be argued that this is not the story Argo set out to tell—and, indeed the story that Argo does tell is well spun—the film has missed an opportunity to remind its viewers that the story of Iran’s revolution is a tragic tale with many victims besides the American hostages. It misses the opportunity to humanize the Iranian people as they slowly come to realize that they have deposed one dictator for another, and that this continues to be the state of affairs in that country.

Given the current state of Iranian-western relations, dehumanizing Iranians and ignoring the complexities of Iranian society and history only furthers misunderstanding.

You might also like:

An article by Tony Mendez entitled, “A Classic Case of Deception: How the CIA Went Hollywood” describing his recollections of the operation.

Photo Credits:

US embassy employee Barry Rosen after being taken hostage in 1979 (Image courtesy of Wikipedia)

Film still of Ben Affleck portraying CIA agent Tony Mendez

Ruhollah Khomeini returning to Iran, February 1, 1979 (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Anti-Shah protestors demonstrating in Tehran, December 27, 1978 (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Images used under Fair Use Guidelines: See Wikipedia:Non-free content.