Lit by fiery amber torchlight, rows of samurai stand shoulder to shoulder as their lord, Yoshii Toranaga, strides toward his stage. The English-born foreigner John Blackthorne, blue-eyed and bewildered, listens through a translator as Toranaga announces that, in return for saving his life, Blackthorne will be granted land, servants, kimonos, and two swords. He is now a samurai, his translator says, and there is a sense that this moment has changed the course of his life.

This scene in the 1980 television miniseries Shōgun captivated millions of American viewers, who accounted for one-third of all households when it aired.[1] Based on James Clavell’s 1975 novel of the same name, the miniseries sparked renewed interest in the novel and nurtured a growing Orientalist fascination in the West, to the point that many articles on the cultural phenomenon credit it with popularizing sushi for Americans. Its protagonist, Blackthorne, was inspired by a real English sailor named William Adams, whose life in seventeenth-century Japan became the seed for one of history’s most persistent cross-cultural narratives. Yet the William Adams of record—a navigator, merchant, and retainer of Shogun Tokugawa—has been largely eclipsed by the samurai Adams of mythmaking. It then begs the question: who was the real man behind the myth?

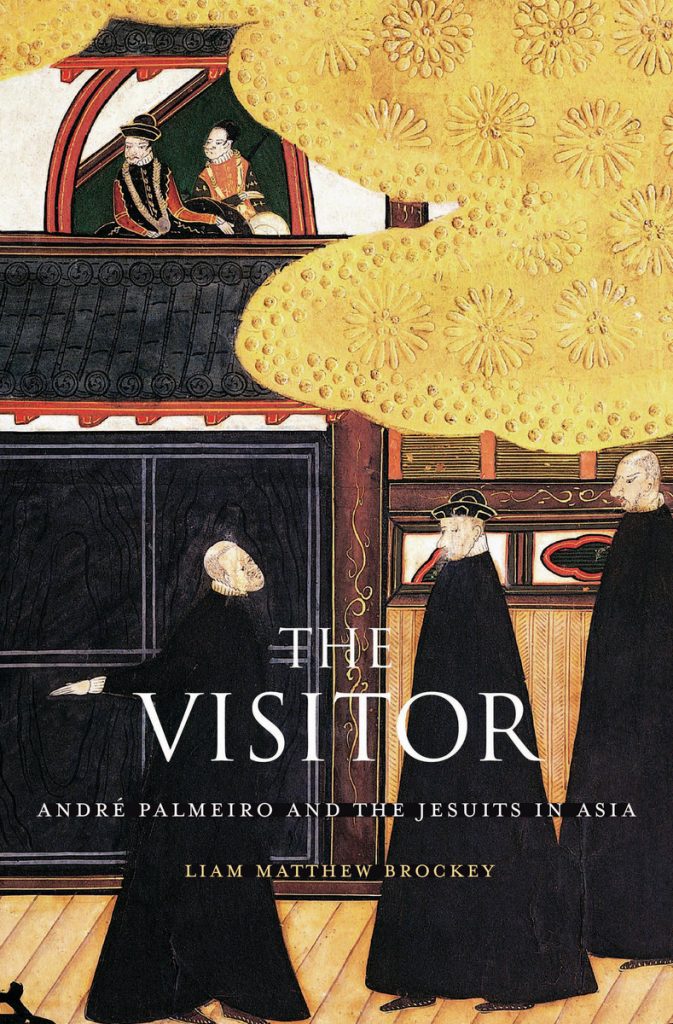

Born in Gillingham, England, Adams began as an apprentice shipwright and later joined the Royal Navy during the Anglo-Spanish War. Employed by a Dutch trading fleet as pilot-major, Adams set sail from Rotterdam in 1598, bound for Asia in hopes of buying spices and other foreign goods. The journey was disastrous. Only one of the five ships survived the grueling two-year voyage, reaching Japan in 1600 with only a handful of starving sailors still able to walk.

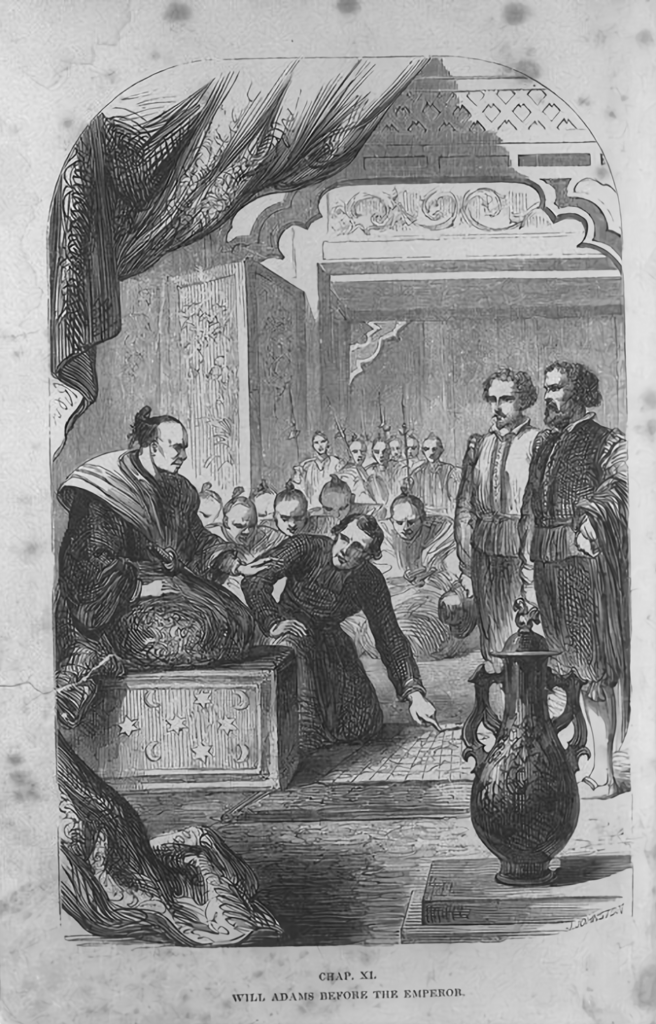

William Adams before Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Adams’s arrival in Japan could easily have ended in execution. The Portuguese Jesuits had already been active in Japan for fifty years, having established a Catholic Christian and European trade monopoly on the island chain.[2] The Portuguese had exclusive trading rights between Japan and the rest of Asia, giving them significant power and influence. But Tokugawa Ieyasu, then a powerful warlord on the cusp of becoming shogun, summoned Adams for questioning. Through an interpreter, Adams explained European affairs and maritime trade, information that likely broadened Ieyasu’s understanding of Western politics and offered him greater insight into the Jesuit influence as well as European rivalries.

After Ieyasu’s victory at the Battle of Sekigahara later that year, he summoned Adams again and asked him to build a Western-style ship. The Englishman succeeded, and Ieyasu rewarded him with land, servants, and an annual stipend, which made Adams a hatamoto, a direct retainer of the shogun. “The emperor had given me a living,” Adams wrote in his letters, “as in England a lordship.”[3] In keeping with his status, Adams may have owned several katana and wakizashi, which are mentioned in his will. He married a Japanese woman, fathered two children, and remained in Japan until he died in 1620.[4]

While Adams accomplished much more than just shipbuilding during his time in Japan, these are little discussed in retellings. Instead, he would take on an entirely new life. William Dalton’s Will Adams, The First Englishman in Japan, published in 1861, is regarded as the first fictionalized biography of the sailor. Written from the perspective of one of Adams’s shipmates, the story transforms him into an archetype of British virtue: a noble, Christian gentleman who wins Japan’s admiration through personal honor and trade. Dalton’s version of Adams embodied the ideals of Victorian mercantilism and national pride more than historical fact.

In 1872, journalist James Walters claimed to have discovered Adams’s tomb in Japan, which sparked renewed interest in his story. Though the grave was known to the local Japanese, Walters’s publication sent waves through Great Britain, bringing awareness to their lost countryman whose homeland had largely forgotten him. As historian Derek Massarella notes, after Walters’s article in The Far East Journal was published, the myth of William Adams truly “took wing.” At a time when Britain sought to frame its imperial history as one of exploration and enlightenment, Adams became a convenient symbol: the brave, lone Englishman forging peaceful relations with an exotic ally.

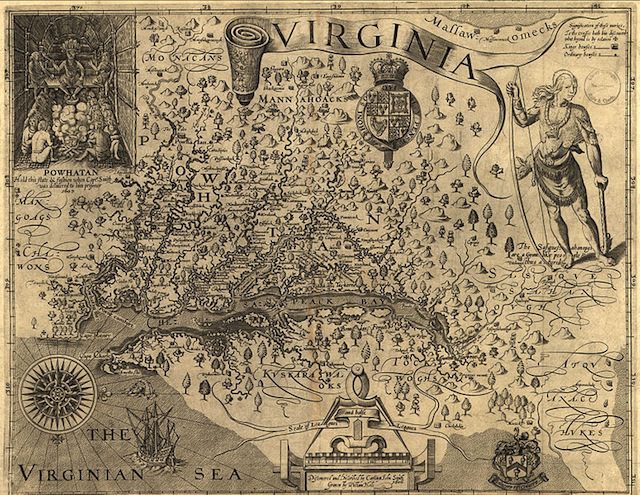

Map of Japan with William Adams who visits the Shogun in 1707. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Arthur Diósy’s 1904 essay “In Memory of Will Adams: The First Englishman in Japan” continued to build on this concept. Writing amid the newly formed Anti-Russian Anglo-Japanese Alliance, Diósy cast Adams as a bridge between two island nations bound by “mutual respect, sympathy, and interest.” He claimed that Adams adopted Japanese dress and “wore two swords,” a detail not mentioned before, but one that would profoundly shape later retellings. With Diósy, the image of Adams as a samurai began to solidify as a reflection of British admiration for Japan’s rise as a modern imperial power, especially considering the two countries’ alliance during the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War that same year.

The myth reached new heights in 1975, when novelist James Clavell published Shōgun. Clavell, a British Royal Artillery veteran, was captured by Japanese forces during the Second World War and was held captive in Changi, Singapore. His experience as a prisoner of war in a place where only 1 in 15 prisoners survived greatly influenced the rest of Clavell’s life and career.[5] Those incredibly challenging years did not harden into resentment for Clavell but instead became the inspiration and fascination that drove much of his writing. Clavell’s epic novel, based loosely on Adams’s story, recast Adams as John Blackthorne, a rough-edged, adventurous, and spiritually reborn figure in Japan. This version diverged significantly from earlier portrayals: John Blackthorne is gritty and tough, but also charming and adaptive, not afraid to get his hands dirty. His loyalty to the shogun, his romance with his translator, and his adoption of Japanese customs all dramatized the allure of cultural transformation. This version of Adams proved to be one of the most enduring. In an article for the New York Times, writer Webster Schott described Clavell’s novel as “so enveloping that you forget who and where you are.”[6]

The spectacle of a Western man mastering samurai ways captivated audiences with the 1980 television adaptation and cemented Adams’s new identity in the public consciousness. In the decades since, Adams’s myth has grown in digital form. The Encyclopedia Britannica wrote its first digital entry on Adams in 1998, and Wikipedia first mentions him in 2003, titling his life “From seaman to samurai.” YouTube videos and historical explainers perpetuate this image, often referencing Clavell’s novel more than Adams’s own letters. The story’s latest revival came with FX’s 2024 Shōgun series, which reached nine million streams in a month and introduced Blackthorne to a new generation.[7] Even with a more nuanced portrayal, the myth remains: William Adams, the Englishman who became a samurai.

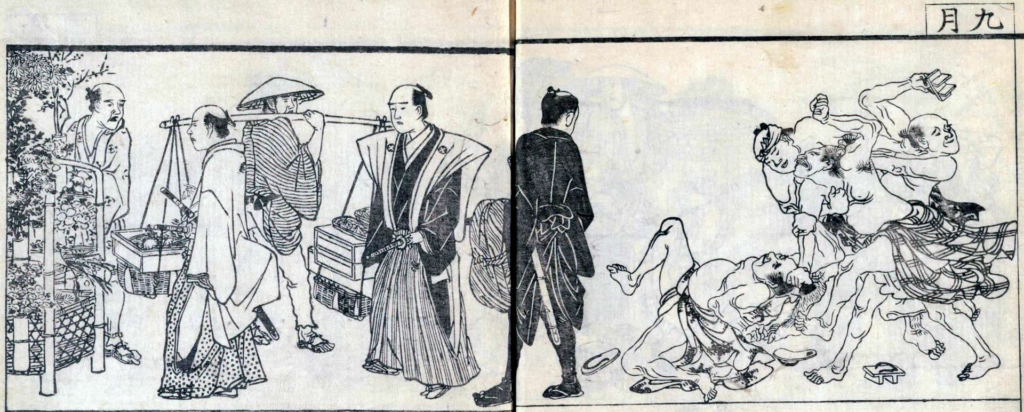

Samurai in the Edo period walking through town. Source: Wikimedia Commons

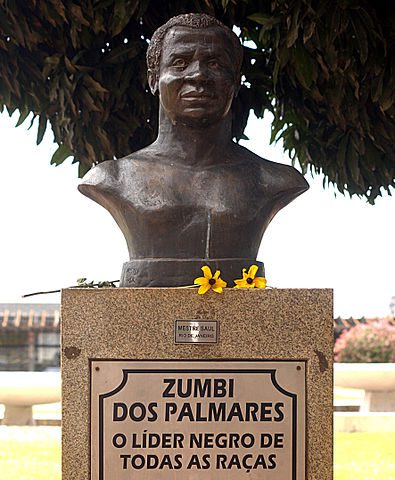

The irony, of course, is that Adams was a samurai in title only. By 1600, samurai were increasingly bureaucrats rather than sword-wielding knights. In his article “Death, Honor, and Loyalty: The Bushidō Ideal,” Cameron Hurst credits this image to the efforts of Nitobe Inazō, who created the concept of Bushidō, the samurai “code of conduct,” through his novel of the same name. The irony? Nitobe was isolated spatially, culturally, religiously, and linguistically from Meiji Japan, with a limited and highly selective understanding of Japanese history and literature. If one tries to trace the historical origins of bushido before Nitobe’s 1899 classic, anything that remotely resembled Nitobe’s “version” was often out of touch with the broader spectrum of Confucianist thought, which most of the samurai class had adhered to for centuries.[8] Given the reality of the two hundred years of peace following shogun Tokugawa’s reign, it would have been far less likely to be in a situation where seppuku would be necessary or even appropriate, despite Nitobe’s claims. In the words of Hurst, “What is the role of the warrior in an age of peace?”[9] William Adams, while definitively a samurai in title, was nothing like the samurai with which popular consciousness is familiar, making his historiographical journey particularly ironic. The days of serving a powerful warlord through prowess on the battlefield had long passed by the time Adams arrived in Japan.[10] In a time when samurai were beginning to turn toward bureaucratic government service, the idea of Adams being a sword-toting, battle-hardened samurai becomes even more fantastical.

The persistence of Adams’s myth reveals more about the cultures that retold his story than about the man himself. In the nineteenth century, he represented British trade and empire. By the early twentieth century, he had become a symbol of friendship between East and West. In the postwar world, he became a vessel for Western fascination with Japanese discipline and mystique. Each reinvention reflected changing desires for connection, heroism, and cultural adaptation.

For a man who spent his life navigating between worlds, perhaps it’s fitting that William Adams remains suspended between fact and fiction. Adams stands independently of even his own writings. The myth has eclipsed the Adams of the original letters. Now, Adams, the samurai, is the most prevalent mythologized version of the real historical figure and is likely to remain so.

Josefine Lin is a recent graduate of the University of Texas at Austin, having written her capstone on the study of public memory and popular history. As a history major and Philosophy of Law minor, she participated in the Normandy Scholar Program in May of 2024. Her research interests include material culture, anthropology, and the Second World War.

[1] Cobb, “Despite ‘Shōgun’ Success, TV Is Falling Out of Love with the Miniseries,” TheWrap. https://www.thewrap.com/shogun-history-and-future-of-miniseries/

[2] Frederik Cryns, “In the Service of the Shogun,” 37

[3] Cryns, 125

[4] Cryns, 214

[5] Grimes, “James Clavell, Best-Selling Storyteller of Far Eastern Epics, Is Dead at 69,” The New York Times.

[6] Webster Schott, “Shōgun: From James Clavell with tea and blood,” The New York Times, June 22, 1975. https://nyti.ms/4lT2ZIU

[7] Otterson, “’Shogun’ Hits 9 Million Views and Beats ‘the Bear’ Season 2 as FX’s Biggest Hulu Premiere,” Variety.

[8] Hurst, “Death, Honor, and Loyalty: The Bushidō Ideal,” 512

[9] Hurst, 521

[10] Michael Wert, Samurai: A Concise History, 78

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

![Description des Indes Occidentales [Description of the West Indies]. Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas. Amsterdam: M. Colin, 1622. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)](http://notevenpast.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/tordes.jpg)