by Ellen Mcamis

Freedom at Midnight paints a sweeping picture of the tumultuous year of India’s independence from Great Britain in 1947. The narrative style of the book immerses readers in the visual landscape of the falling Raj and allows them to step into the minds of the great actors of this time. This sort of narrative history also contains drawbacks that limit our understanding of this important moment.

The book compresses the story to a tight one-year time frame. This allows Collins and Lapierre to focus on the state-level negotiations on India’s independence. It begins with Louis Mountbatten’s installation as the Last Viceroy of India, and closely follows the negotiations between Mountbatten, Whitehall, Jawaharlal Nehru, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, and Mohandas Gandhi as they make the decision to partition India. It then continues with the chaos and bloodshed of the split, until ending with Gandhi’s assassination in 1948. This narrative is undeniably fascinating, however, it also places an almost exclusive emphasis on the “great men” of history. They are represented here as isolated personages who hold the fate of the Indian people in their hands. The people themselves are often lost in this depiction, appearing as faceless masses helplessly reacting to political machinations.

The book compresses the story to a tight one-year time frame. This allows Collins and Lapierre to focus on the state-level negotiations on India’s independence. It begins with Louis Mountbatten’s installation as the Last Viceroy of India, and closely follows the negotiations between Mountbatten, Whitehall, Jawaharlal Nehru, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, and Mohandas Gandhi as they make the decision to partition India. It then continues with the chaos and bloodshed of the split, until ending with Gandhi’s assassination in 1948. This narrative is undeniably fascinating, however, it also places an almost exclusive emphasis on the “great men” of history. They are represented here as isolated personages who hold the fate of the Indian people in their hands. The people themselves are often lost in this depiction, appearing as faceless masses helplessly reacting to political machinations.

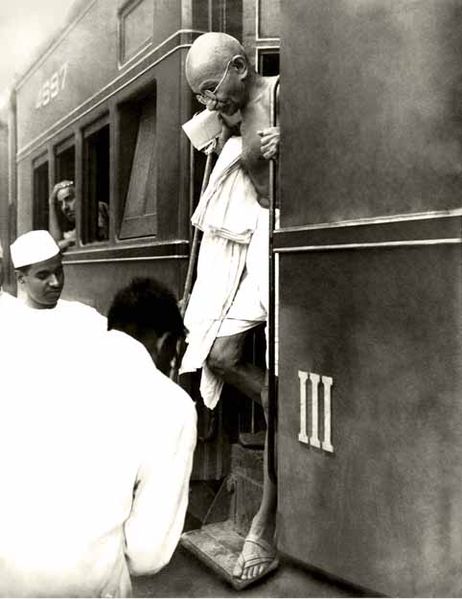

Mahatma Gandhi (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Mahatma Gandhi (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Despite this focus on the agency of the great men, the primary mechanism which forces history forward in the book is destiny or fate. In this account, the British were “a race that God had destined” to rule the Indians, and therefore “naturally acquired” India. Faced with the prospect of division, Mountbatten must “save India” from itself. This device frees Mountbatten and the British from the charge of poorly handling or rushing independence. Instead, they are depicted as contending with historical inevitabilities far more powerful than themselves.

While a current reader does not expect a highly sympathetic and nuanced portrait of India from a book written three years before Edward Said’s Orientalism, and the rise of post-colonial studies, as a narrative with insight into the rush of daily life on the cusp of independence, it remains an enjoyable and exciting read.

Sundar Vadlamudi’s review of “Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and his Struggle with India.”

Amber Abbas’ review of “Prejudice and Pride: School Histories of the Freedom Struggle in India and Pakistan.”

Jack Loveridge’s reviews of “Wavell: the Viceroy’s Journal,”“Jawaharlal Nehru: A Biography,”“The Decline, Fall, and Revival of the British Empire,” and “The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan.”

Voices of India’s Partition, Part V: Interview with Professor Mohammad Amin

Voices of India’s Partition, Part IV: Interview with Professor Masood ul Hasan

Voices of India’s Partition, Part III: Interview with Professor Irfan Habib

Voices of India’s Partition, Part II: Interview with Mr. S.M. Mehdi

Voices of India’s Partition, Part I: Interview with Mrs. Zahra Haider