by Amber Abbas

Professor Mohammad Amin is a distinguished professor of History who spent his entire career in St. Stephen’s College, one of the founding colleges of Delhi University.

During his years at Aligarh, he was trained by Professor Mohammad Habib (Father of Professor Emeritus Irfan Habib). He remarked that Aligarh was known for its liberal History Department, which “later turned completely red.” His own priorities were in writing narrative histories of the medieval period. He described his own position as a skeptic, “History is not neat and tidy. If you find that you have an answer, I am very skeptical about it. How can there be a rational explanation for the irrational acts of irrational people?”

In this interview, Professor Amin reflects on his experiences at Aligarh during late 1940s, when the Muslim League was dominant and “Aligarh really was bristling with the movement for Pakistan.” Students were being dispatched into the hinterlands to spread League propaganda in 1945 and 1946 as India prepared for elections. Aligarh was considered so important as a center of Muslim opinion-making that, he tells me, if a meeting was taking place in the Union (the seat of student government), stores would close in towns and villages nearby as the community awaited news of Aligarh’s pronouncements on the important issues of the day. This centricity to Muslim opinion was key in placing Aligarh at the heart of the Pakistan movement. Amin, like narrator Masood ul Hasan, describes an atmosphere of youthful enthusiasm in which students were caught up in the political excitement of the time.

During the partition, however, as Amin’s story reveals, Aligarh became a site of suspicion; Muslims were targeted as potential traitors to the state, and Aligarh was especially vulnerable because many students had been active in calling for independent Muslim statehood. Amin mentions that as he returned to Aligarh in late summer 1947, he had been advised to carry a book with the name of a Hindu inscribed inside, so as to distract attention from his own Muslim identity. Trains, as he reminds me, were sites of massacre during the communal unrest that accompanied partition and on both sides of the border trains pulled into stations full of dead bodies. His return to Aligarh in 1947 was tense, but uneventful.

In remembering this, Amin moves directly to the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi. He connects Gandhi’s assassination to the atmosphere at Aligarh by describing it as particularly “telling.” On the day of the assassination, Amin was headed into the city—the predominantly Hindu city of Aligarh separated from the precincts of the Aligarh University by a railway line and a bridge. By the time they reached the city, now a few kilometers distant from their university and its protective walls, people shouted at them to “Go back!” Though they simultaneously heard that Gandhi’s assassin had been a Hindu, the students felt the threat of violence in the city, and those around them sternly directed them to return to the right side of the tracks.

Amin remembers how important Gandhi had been in preserving a tenuous peace in Eastern India during the chaos of 1947. Having gone on a fast to the death, he refused to break it until leaders of the three major faiths of the region: Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs came together to make a joint pledge to stop the fighting. In the moments after Gandhi’s death, Amin and his friends reaped the benefit of his magnanimity- they returned safely to their school- but they knew, as did those around them, that the situation remained tense enough to go either way.

LISTEN TO THE ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW HERE

READ THE ORAL HISTORY TRANSCRIPT HERE

Photo credits:

Amber Abbas, untitled portrait of Professor Mohammad Amin

Author’s own via Not Even Past

Jama Masjid, “AMU-Aligarh,” Decemer 23, 2009

Author’s own via Flickr Creative Commons

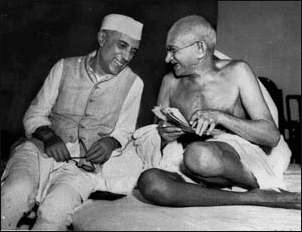

Unknown author, Untitled Portrait of Mohandas Gandhi and Jawharlal Nehru, July 6, 1946

AP Photo/Max Desfor via Flickr Creative Commons

You may also like:

Voices of India’s Partition, Part IV: Interview with Professor Masood ul Hasan

Voices of India’s Partition, Part III: Interview with Professor Irfan Habib

Voices of India’s Partition, Part II: Interview with Mr. S.M. Mehdi

Voices of India’s Partition, Part I: Interview with Mrs. Zahra Haider