by Janine Jones

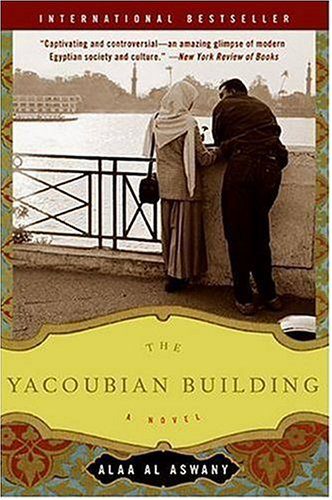

Alaa al-Aswany’s novel The Yacoubian Building (2002, Arabic عمارة يعقوبيان) tells the story of a group of people loosely bound together by dint of living in the same crumbling building – a real place – in downtown Cairo. The son of a doorman; an older man with an endless fascination for women; the secret second wife of a  wealthy and corrupt businessman; and a lonely newspaper editor looking for lasting love, are each connected to the building, either because they rent office space there, or have an apartment there, or visit someone who lives there. A scathing indictment of governmental corruption and a critique of the class-based limitations of contemporary Egyptian society, Yacoubian Building is nevertheless a piquant and entertaining read.

wealthy and corrupt businessman; and a lonely newspaper editor looking for lasting love, are each connected to the building, either because they rent office space there, or have an apartment there, or visit someone who lives there. A scathing indictment of governmental corruption and a critique of the class-based limitations of contemporary Egyptian society, Yacoubian Building is nevertheless a piquant and entertaining read.

The Yacoubian Building gained notoriety in Egypt for being one of the first novels to break the homosexual taboo by featuring an openly gay character. The half-French, half-Egyptian editor of the fictional (French) newspaper Le Caire, Hatim Rasheed is portrayed sympathetically. Although other characters talk about him disparagingly he has nevertheless managed to gain the respect – or, at least, the quiet tolerance – of most of his neighbors and associates. Rasheed’s least sympathetic moment is not one related to his sexuality, but to his sense of class entitlement. He is deeply in love with a poor married Nubian man, Abduh, whom he has been supporting financially and with whom he has been having an affair. When Abduh’s child dies a sudden death, he is convinced that God is punishing him for engaging in forbidden sexual acts, and breaks off the affair. Rasheed, who wants a long-term committed relationship and has no interest in cruising the gay bars, seeks out Abduh and hopes to lure him back, promising him job security if they can only have one more night together. Abduh, deeply in debt and still racked with guilt, consents to one night in the hope of getting back on his feet. When Abduh gets up to leave, a drunken Rasheed demands that he stay, threatening and raving as though Abduh is nothing more than a servant whom Rasheed is entitled to command: “You’re just a bare-foot, ignorant Sa’idi. I picked you up from the street, I cleaned you up, I made you a human being.” While Rasheed’s ugly rant may be interpreted as the distraught sputtering of a heartbroken, inebriated man, the broader notion of entitlement and the economic and sexual exploitation of the poor by wealthy men is is clear here and throughout al-Aswany’s book.

One of the least sympathetic characters among these upper–class men is Hagg Azzam, a nouveau riche entrepreneur and budding politician who has accumulated vast drug wealth under the cover of more respectable, legal business dealings. Corpulent, seedy, selfish and malicious, Azzam typifies the corrupt businessman, justifying all manner of morally dubious behaviors under the veneer of Islamic sanction, denying seemingly even to himself the fact that his own pocketbook provides the necessary suasion with the religious leaders he consults for guidance about right conduct. He is allowed to take a second wife under Islam and to stipulate certain provisions about her behavior in the marriage contract, so he deliberately chooses a poor young widow, Souad, setting her up in an apartment in the Yacoubian building and then treating her little better than a call-girl. Azzam forbids her to see her beloved only son in Alexandria and demands that she not have any more children. When she does get pregnant and wants to keep the baby over his strident objections, he uses his wealth and means to forcibly drug and kidnap her, aborting their baby and divorcing her while she is unconscious. After repudiating her, any regrets he feels are related to sex and sex alone:

“He consoled himself with the thought that his marriage to her, while providing him with wonderful times, hadn’t cost him a great deal. He also thought that his experience with her might be replicable. Beautiful poor women were in good supply and wedlock was holy, not something anyone could be reproached for.”

The Yacoubian Building, No. 34 Talaat Harb, Cairo, Egypt

The Yacoubian Building, No. 34 Talaat Harb, Cairo, Egypt

Nevertheless, despite Azzam’s ruthlessness and apparent lack of conscience, even he can be played by men who are more powerful. In one scene he goes to protest being asked to donate 25% of the proceeds of a business scheme to the powers-that-be, only to be required to sit and wait to talk to the “Big Man,” a disembodied voice piped in from the ether. This critique of the construction of modern Egyptian masculinity around power, intrigue, corruption, and manipulation, continues throughout al-Aswany’s novel.

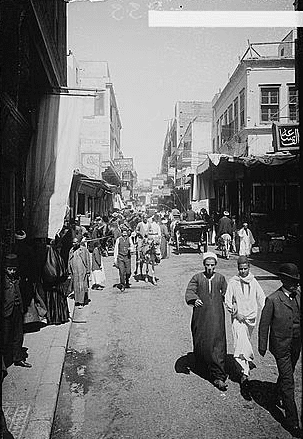

Egyptians on the streets of Cairo in 1920. (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Egyptians on the streets of Cairo in 1920. (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Azzam’s complicated approach to Islam, moreover, reflects al-Aswany’s diverse and nuanced characterization of Egyptian men and their religious sentiments. Although nearly all of the characters in The Yacoubian Building are Muslim, each interprets and understands Islam differently. For example, although it would be difficult to read this text as supportive of radical Islam, al-Aswany paints a sympathetic portrait of Taha el Shazli’s journey into radicalization, as a consequence of social and especially governmentally-imposed emasculation. Despite Taha’s considerable intellectual gifts and willingness to work hard, he is thwarted at every turn, unable to land a decent job because of his lack of connections and the stigma of having been born to a working-class father. His relationship with his first love falls apart as she too falls on hard economic times. Because Taha is unable to marry and provide for Busayna and thereby protect her from the leering, sleazy overtures of her employers, she gradually succumbs to a precarious balancing act of giving sexual favors (as long as they don’t compromise her all-important status as – technically – a virgin) in exchange for job security and increased monetary compensation. Selling herself in such a way, however, embitters Busayna. Though she never tells Taha what economic circumstances have forced her into, she grows cool and distant from him, finally breaking up with him in an almost glib manner in the street. In a sad irony, his increasing religiosity parallels her increasing descent into moral compromise, both a result of economic inequality. Having lost his love and any possibility of a real job, Taha finds meaning in Islam, actively protesting the corruption of the government and advocating for change. He finally finds the dignity and self-respect that broader Egyptian society had robbed him of in his Islamic organization:

“Those who knew Taha el Shazli in the past might have difficulty in recognizing him now. He has changed totally, as though he had swapped his former self for another, new one. It isn’t just a matter of Islamic dress that he has adopted in place of his Western clothes, nor of his beard, which he has let grow and which gives him a dignified and impressive appearance greater than his real age….All these are changes in appearance. Inside, however, he has been possessed by a new, powerful, bounding spirit. He has taken to walking, sitting, and speaking to people in the [Yacoubian] building in a new way. Gone forever are the old cringing humility and meekness before the residents. Now he faces them with self-confidence. He no longer cares a hoot for what they think, and he won’t put up with the least reproach or slight from them.”

No longer obsequious and servile, Taha feels confidence in himself as a man. Any ambivalence he may have felt about his Muslim associations is crushed when he is jailed, tortured, interrogated, blindfolded, and raped repeatedly by jeering police. His sense of alienation and emasculation complete, Taha turns wholly to the anti-nationalist teachings of Gama’a Islamiyya. Even marrying a beautiful Muslim widow (who manages to be sensual, sexy, and modest at the same time) doesn’t deter Taha from his goal of revenge through a martyrdom operation on those of the police establishment who violated him. Al-Aswany’s message is clear: lack of economic opportunity and government violence and corruption are leading to the religious radicalization of young Egyptian men.

(Image courtesy of Gigi Ibrahim/Flickr Creative Commons)

(Image courtesy of Gigi Ibrahim/Flickr Creative Commons)

(Image courtesy of Hossam el-Hamalawy/Flickr Creative Commons)

(Image courtesy of Hossam el-Hamalawy/Flickr Creative Commons)

This last is all the more interesting, relevant, and timely, given the brutal murder of 28-year-old Egyptian student Khaled Said by Egyptian police in front of his home in 2010, and the subsequent Facebook page and protest campaign, called “We are all Khaled Said” (كلنا خالد سعيد ). The viciousness and injustice of the murder served to galvanize public opinion, and was an important catalyst for the uprising, eventually evolving into the still-unfolding Egyptian Revolution.

You may also like:

Yoav di-Capua’s FEATURE piece on his recent book, Gatekeepers of the Arab Past.

Yoav di-Capua’s blog post about political and social conditions in Egypt eight months after Mubarak’s ouster in February 2011.

Lior Sternfeld’s review of Erez Manela’s The Wilsonian Moment.