by Janine Jones

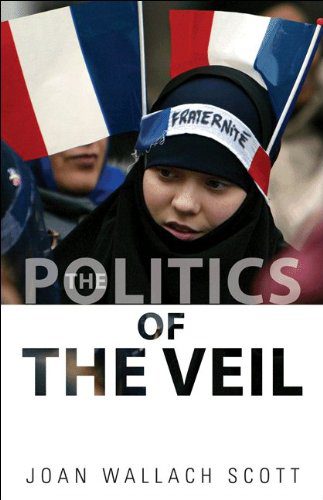

Joan Wallach Scott introduces The Politics of the Veil, about the 2004 headscarf debates in France, with a telling sentence: “This is not a book about French Muslims; it is about the dominant French view of them.” Writing in highly accessible prose, Scott examines the political firestorm surrounding the official French ban on headscarves for girls under the age of eighteen in public schools. She challenges the government’s assertion that headscarves represent chauvinism, sexism, repressive patriarchy, and “anti-modernism” and that they are therefore antithetical to the egalitarian ideals of the French republic. In reality, Scott contends, the headscarf ban typifies the roiling undercurrents of anti-Muslim racism endemic to contemporary French society.

Scott explains that the headscarf ban was justified by appeals to the French republican ideal of secularism. In the French legal system, unlike the American or British, differences of religion (as well as race, sex, etc.) are formally unacknowledged. Instead of being given legal protections based on differences, all are considered first and foremost French citizens, with the underlying ideal that French nationality comes before any other marker of identity. Secularity is designed to protect French citizens from any claims of institutionalized religion (in contrast to the American and British systems, which protect religion from the interference of government). Because of this, “[N]o official statistics are kept on the ethnicities or religions of the population. If differences are not documented, they do not exist from a legal point of view, and so they do not have to be tolerated, let alone celebrated.”

Scott explains that the headscarf ban was justified by appeals to the French republican ideal of secularism. In the French legal system, unlike the American or British, differences of religion (as well as race, sex, etc.) are formally unacknowledged. Instead of being given legal protections based on differences, all are considered first and foremost French citizens, with the underlying ideal that French nationality comes before any other marker of identity. Secularity is designed to protect French citizens from any claims of institutionalized religion (in contrast to the American and British systems, which protect religion from the interference of government). Because of this, “[N]o official statistics are kept on the ethnicities or religions of the population. If differences are not documented, they do not exist from a legal point of view, and so they do not have to be tolerated, let alone celebrated.”

Scott notes that very few girls – a tiny minority – were wearing headscarves to school. There was not a sudden influx of veiled immigrant girls filling French schools. In addition, several of the girls who were involved in setting off the debates had voluntarily adopted the headscarf. These young women had not been pressured into hijab by their fathers, brothers, imams, or local community, but instead had selected to wear the headscarf as an individual choice. Their use of religious garb as a form of pious expression was both fully autonomous and entirely personal. Finally, these girls were wearing a form of hijab that only covers the hair and neck; they were not wearing niqab, the burqa, or other forms of the veil that obscure the face and render the wearer difficult to identify.

The reasons for outrage over the sartorial choices of such a small subset of the population can be traced to French colonial history, Scott contends. Explaining the internal contradictions inherent in the French mission civilisatrice, Scott argues that the assimilationist goals of the French colonizing mission – essentially an attempt to “Frenchify” the colonized – were fundamentally unattainable because the colonized peoples were perceived as un-civilizable. Formal policies of racial and ethnic segregation and discrimination accompanied the French colonial venture in Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco, further distancing the colonizers from the people they were seeking to “civilize.” Nowhere, Scott argues, was this discursive colonial project of “Othering” more evident than in the French treatment of Muslim North African women. Muslim women were figured in a binary opposition as either oppressed, harem-bound victims or the exotic, hyper-sexed prostitutes. Historically, then, the headscarf has long served as a symbol of alterity within France. Contemporary France, dealing with an influx of mostly poor North African immigrants – who are officially citizens – from the former colonies fares little better, as the ban on headscarves, rather than “liberating” young women, perpetuates racist and sexist stereotypes of the Muslims within its midst.

The reasons for outrage over the sartorial choices of such a small subset of the population can be traced to French colonial history, Scott contends. Explaining the internal contradictions inherent in the French mission civilisatrice, Scott argues that the assimilationist goals of the French colonizing mission – essentially an attempt to “Frenchify” the colonized – were fundamentally unattainable because the colonized peoples were perceived as un-civilizable. Formal policies of racial and ethnic segregation and discrimination accompanied the French colonial venture in Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco, further distancing the colonizers from the people they were seeking to “civilize.” Nowhere, Scott argues, was this discursive colonial project of “Othering” more evident than in the French treatment of Muslim North African women. Muslim women were figured in a binary opposition as either oppressed, harem-bound victims or the exotic, hyper-sexed prostitutes. Historically, then, the headscarf has long served as a symbol of alterity within France. Contemporary France, dealing with an influx of mostly poor North African immigrants – who are officially citizens – from the former colonies fares little better, as the ban on headscarves, rather than “liberating” young women, perpetuates racist and sexist stereotypes of the Muslims within its midst.