Open a news website these days and there’s likely to be a story about violence in the Middle East. There’s a good chance that the article will refer to extremist Islamists, possibly even mentioning the rising tide of anti-Western sentiment in the Middle East more broadly. Among academics, pundits, and politicians there is no shortage of opinion on why this state of affairs exists. Explanations often attribute anti-Westernism (and more specifically, anti-Americanism) to a “clash of civilizations,” drawing on the assumption that Middle Easterners (and, more specifically, Arabs) refuse to accept a secular, peaceful, democratic global order. All too often, the history of the Arab-American relationship is subject to misunderstanding and misuse by both Arabs and Americans seeking to forward a particular political agenda.

Missing from the conversation is a critical examination of the decisions and forces that contributed to our current situation. The question of “Why?” has become a minefield of polemic, even for historians—what we need instead is to ask “How?” How did suicide bombings and invasions become the norm? How did refugee camps and political assassinations become routine? How did we get here?

Ussama Makdisi seeks to answer this question by using American and Arab voices to tell a nuanced story of events in the past century. He recounts a tale of mutual disenchantment, of reciprocal misunderstandings and an increasing—though not inevitable—opacity. He punctuates this broad narrative with moments often evoked in histories of the relationship: British colonialism, American support of Israel, the 1967 war, the oil embargo, etc. However, Makdisi is careful to dissect these events, delving into their complexity and texture. Moreover, he draws into his narrative less visible moments, giving new weight to often overlooked incidents, such as President Eisenhower’s intervention in Lebanon in 1958, which many Arabs saw as an infringement on Lebanese sovereignty to protect American interests. Unlike many other histories of America’s relationship to the Middle East, Makdisi reinforces the contingency of historical outcomes, underlining the missed opportunities and moments of apparent engagement that might have led to different paths.

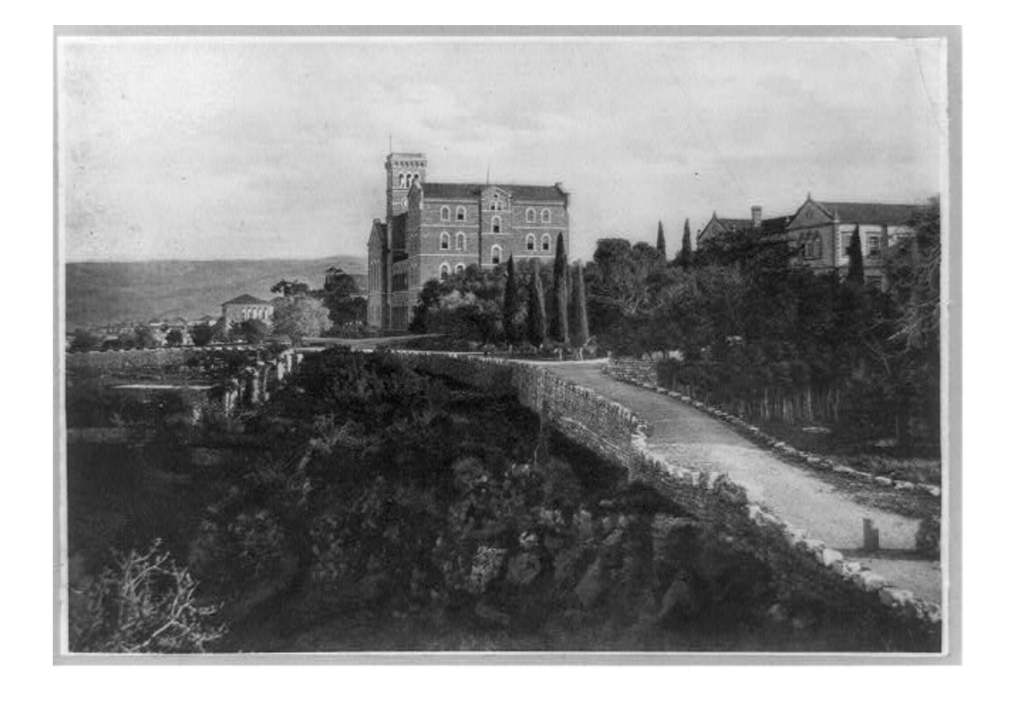

Makidisi’s story begins not at the dawn of Islam or during the crusades as many “clash of civilizations” narratives do, but rather with the arrival of evangelical missionaries in the Holy Land in the late 19th century. Though these men and women arrived in the Protestant spirit of conversion, they quickly found the Bible had lost some value as a reliable travel guide over the course of nearly 1,000 years. An ethnically and religiously heterogeneous region for millennia, the Levant was not a stable foothold from which the missionaries could launch their latter-day spiritual crusade. Makdisi skillfully tracks how, instead of leaving, most missionaries took the surprise in stride and the mission of conversion evolved into a mission of education with the establishment of institutions like the American University of Beirut based on Western educational ideas. Never losing the hope of long-term conversion, missionaries in the region adapted their fantasies to the realities of the region and encouraged a community of understanding and respect. Arab intellectuals saw in American ideals of democracy a parallel to their own struggle for freedom from the imperial yoke of Britain and France; the second generation of Western missionaries who grew up in the Middle East had a more nuanced appreciation for the diversity and dynamism that characterized the region. Not until the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century did this begin to fray. The failure of Wilsonian principles of self-determination at the 1919 Paris Peace coupled with Western concern about massacres of Armenians in Turkey were the first significant breaches in the relationship.

Another important watershed moment for Makdisi occurs in 1948 with the declaration of the state of Israel, which was and remains the foundational event for much of the 20th and 21st century turmoil in the Middle East. Today, many Americans take support for Israel for granted as a natural state of affairs. Makdisi skillfully disassembles this assessment, describing President Truman’s decision to recognize Israel shortly after its creation as hotly contested by many prominent members of the Truman administration, including Secretary of State George Marshall and US diplomat par excellence George Kennan. These men and their supporters were reluctant to undermine America’s strategic relationship with Arab states and skeptical of the long-term benefits of an alliance with Israel. But, as Makdisi points out, even recognition of Israel was not initially antithetical to accord between Arabs and Americans: American support for Israel made Arabs suspicious of American interests, but not fundamentally hostile to American values of democracy and capitalism.

Makdisi’s book whips through the last half of the 20th century, chronicling a series of moments in which entrenched incomprehensibility and bureaucratic inertia underpin an atmosphere of escalating rhetoric, and, eventually, violence. For Makdisi, this is a story as much about anti-Arabism in America as it is about anti-Americanism in the Middle East. He notes the acerbic racial stereotypes that proliferated in American popular culture during the 1970s. A cursory glance at political cartoons about the oil embargo or airplane hijackings provides cringe-worthy proof of casual xenophobia directed toward Middle Easterners. Here is where the narrative enters into all-too familiar grounds. As rhetoric on both sides has become more extremist, violent incidents have increased in scale and frequency. Terrorists and occupying armies are part of the same violence, Makdisi argues, and represent not the cause of Arab-American antipathy but its symptoms.

The book ends on a hopeful, if inconclusive note. Faith Misplaced does not answer the question of whether there is a place for the U.S. in a peaceful Middle East, nor does Makdisi offer concrete ideas about what solutions might look like. Yet, to his credit, he avoids the pessimism that plagues many scholars of the region. Politics, argues Makdisi, led us to our current circumstances, and politics—presumably with a more nuanced understanding of recent history—holds hope for the future.

Ussama Makdisi, Faith Misplaced: The Broken Promise of U.S.-Arab Relations (New York: PublicAffairs, 2010)

You may also like:

Lior Stanfield’s review of The Israeli Republic, by Jalal Al-e Ahmad (2014)

Kristin Tassin on Contending Visions of the Middle East: The History and Politics of Orientalism, by Zachary Lockman (2004)

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.