By Brian Levack

Magna Carta has often been hailed as a statement of fundamental law, the basis of the English constitution, a defense of individual liberty, the establishment of the rule of law, and even the foundation of English democracy. Actually, it was none of these.

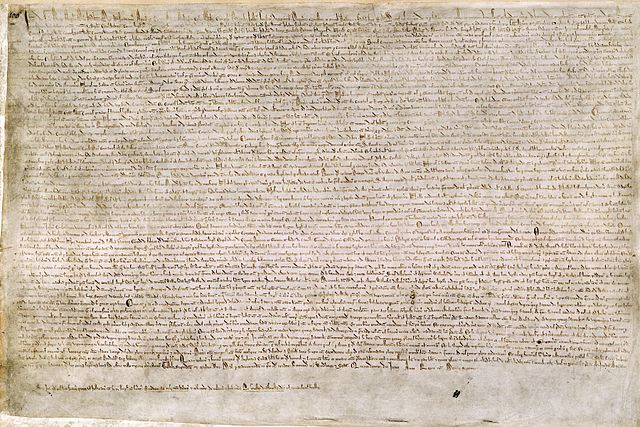

One of four known surviving 1215 exemplars of Magna Carta. This document is held at the British Library and is identified as British Library Cotton MS Augustus II.106.

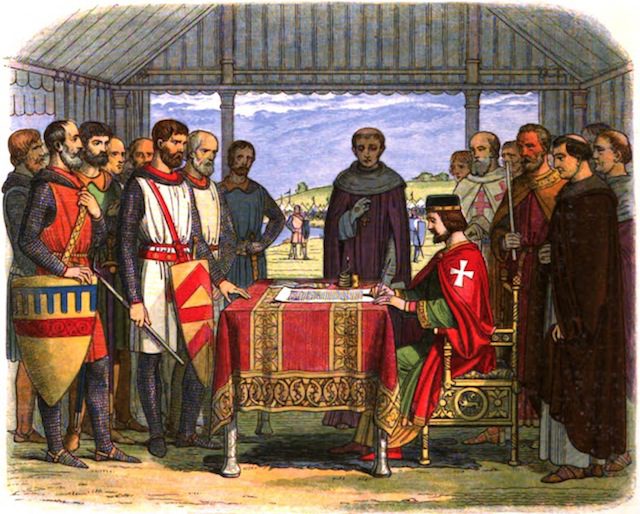

It is true that the Great Charter, which was signed 800 years ago in June 1215 by 24 rebel barons and the Lord Mayor of London and witnessed by 12 bishops and 20 abbots, did succeed in obtaining King John’s recognition of a long list of liberties of the nobility, the towns, and the clergy. But it is important to understand that liberties — note the plural form — in medieval England were considered specific exemptions from royal control rather than the exercise of individual political, social and economic freedom, which nineteenth-century liberals sought to promote and protect. The preface to Magna Carta also proclaimed the freedom of the English Church, but that was the freedom of the clergy to conduct its own business, such as holding elections without royal interference. It did not establish the institutional independence of the Church from the state or change the traditional legal arrangement by which the clergy held their land in the king’s name.

King John on a stag hunt. King John of England, 1167-1216. Illuminated manuscript, De Rege Johanne, 1300-1400

Magna Carta also defended the common law rights of landowners, but those specific property rights should not be confused with the inalienable rights proclaimed in the American Declaration of Independence or the French Declaration of the Rights of Man of 1789. Nor did the limitations on royal power enumerated in this charter establish the rule of law. That constitutional principle was not fully realized in England until the seventeenth century at the earliest.

Finally, this document, which guaranteed specific legal rights of the landed class, had nothing to do with the introduction of democracy, which was not achieved in England until parliament granted the vote to all adult males in 1918 and to women in 1928.

Magna Carta and the subsequent parliamentary statutes confirming it were the product of negotiation and compromise between the nobility and the clergy on the one hand and the monarchy on the other. The first draft of the document, which is now lost, demanded more concessions from King John than the final version signed at Runnymede on June 15. Magna Carta was in fact a peace treaty, drafted by the archbishop of Canterbury, that attempted—unsuccessfully in the end—to resolve a growing conflict between a faction of the English nobility and a financially strapped king—a conflict that erupted in the First Baron’s War of 1215 after Magna Carta was signed and continued throughout the following three centuries. Although Magna Carta was confirmed by Parliament at least 32 times, it was also ignored for long periods, and it was not always treated with the reverence that it commands today in England and The United States. During the Tudor period, when royal power was significantly enhanced and the crown managed finally to suppress the independent power of the great magnates of the kingdom, Magna Carta was hardly ever mentioned. In the early sixteenth century there was even a temporary revival of the reputation of King John, the antagonist of the barons and the clergy at Runnymede, both for the king’s efforts to strengthen royal power and for his attack on the English Church, over which the Tudors acquired control at the time of the Reformation. In the 19th and 20th centuries almost all of the 63 clauses of Magna Carta were repealed, a striking testament to its irrelevance to modern constitutional law.

And yet Magna Carta, viewed as a constitutional icon and statement of individual liberty, has persisted to the present day. The document is still treated with a reverence similar to that of our own Constitution, and hundreds of people visit Runnymede every year, where a monument was constructed in 1957 by none other than the American Bar Foundation. In this 800th anniversary year all four surviving copies of the charter are on display at the British Library.

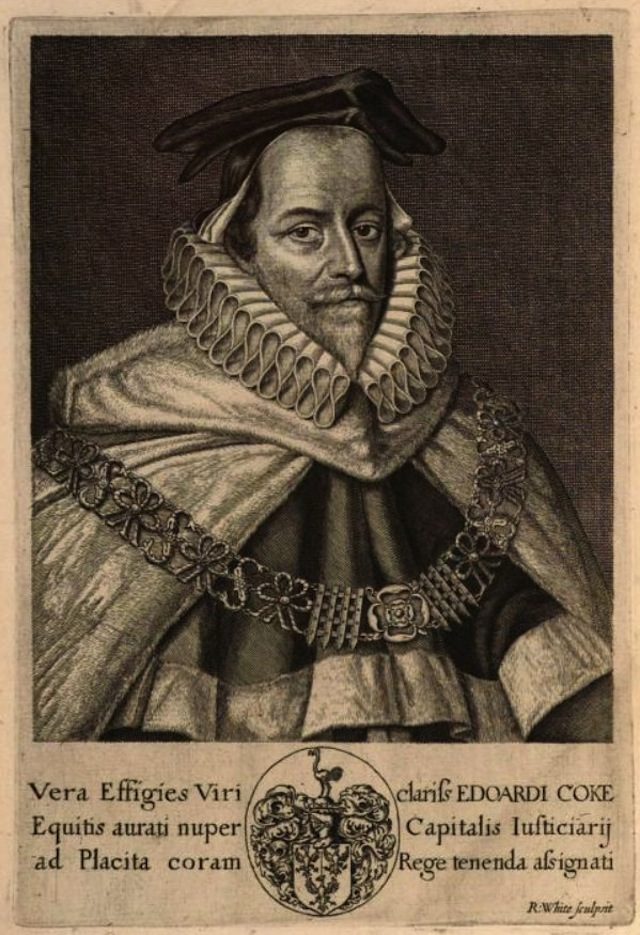

So how did this quintessentially medieval document acquire its iconic status as the foundation of the English constitution and a statement of what we call fundamental law? The key figure in this documentary make-over was Sir Edward Coke, the greatest English jurist of the seventeenth century, and the occasion was the Parliament of 1628, more than 400 years after Magna Carta was signed.

At that time Coke and his allies in the House of Commons attempted to place limits on Charles I’s use of the royal prerogative (the power the king exercises by himself) by passing the Petition of Right, which declared that English subjects could not be denied certain rights at the common law. During the war with Spain in the first three years of Charles’s reign (1625-28), the king had forced some of his wealthier subjects to lend him money with no guarantee of repayment, imprisoned men without showing cause (for refusing to lend the money), quartered soldiers in English towns without compensating those who housed them, and declared martial law in the parts of England where the army was stationed. During the debate on the Petition of Right, Coke argued that the king could not violate these rights under any circumstances, even in a time of war, because the king was under the law rather than above or outside it. In order to buttress this claim, Coke and his fellow MPs, supported by a group of antiquarians who rummaged through the records of parliament stored in the House of Lords, constructed the myth of the ancient constitution, which they claimed had originated in the misty Anglo-Saxon past and took precedence over the subsequent growth of royal power. According to Coke, the clearest written expression of this mythical ancient constitution was Magna Carta, which he transformed from a remedy of the specific grievances of wealthy landowners into a guarantee of the property rights and personal liberty of all freeborn English subjects. Coke could not have been clearer in this anachronistic historical exposition. According to Magna Carta he said, ”every free subject of this realm hath a fundamental property in his goods and a fundamental liberty of his person.”

Now, there is good reason to celebrate Coke’s achievement in this regard. His reinterpretation of Magna Carta made a significant contribution to the acceptance of such hallowed constitutional principles as the rule of law, due process, and the claim, first made by John Adams in 1779, that we are a government of laws, not of men. In the conflict leading up to the American Revolution, colonists invoked the authority of Magna Carta to support their concept of “liberty” and independence from Great Britain, casting George III in the role of a the tyrannical King John. But as we recognize Coke’s achievement in this regard, we should also recognize that this brilliant jurist was not a very good historian. Not only did he invent an ancient constitution that had never existed, but he practiced what we now call Whig history—taking a document or an event (in this case Magna Carta) out of its proper historical context and making it out to be more modern than in fact it really was.

All images via Wikipedia.