“How low do you have to stoop in this country to be President?”

Forty years on, that question still haunts the pages of Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72 like the ghost of Boss Tweed. First appearing as a series of articles in Rolling Stone Magazine, Thompson’s coverage of the 1972 presidential election shines light on the darker side of the democratic process. Thompson, author of Hell’s Angels and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, has the right kind of eyes to see the corruption, the lunacy, and the sheer depravity of choosing a chief executive in modern America. In his landmark work of Gonzo journalism, Thompson chronicles the Democratic Party’s struggle to mount a viable challenge to Richard Nixon as the Vietnam War raged on with no end in sight.

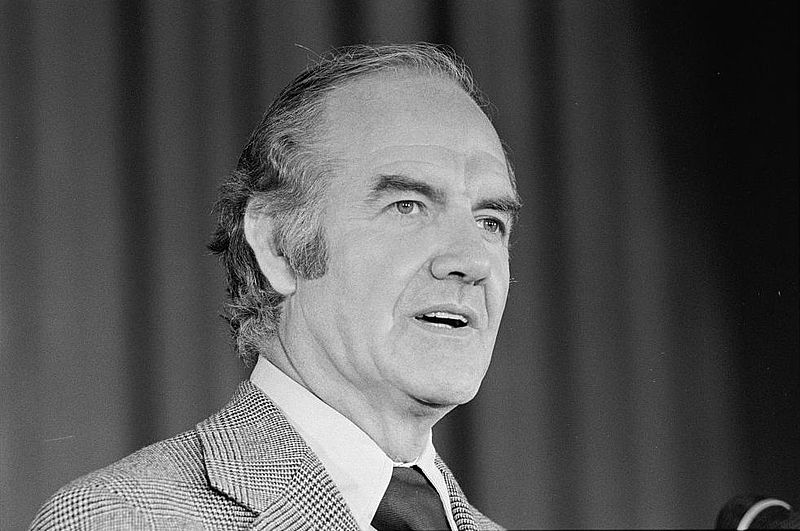

Thompson powerfully sets the stage for the 1972 Democratic primary contest – a party divided, old coalitions fragmenting, and the chaos of the 1968 election looming over the process. For the first time, the Democrats would choose their nominee exclusively through state primaries rather than a combination of elections and back-room deals. The list of candidates – including Sen. Ed Muskie of Maine, Sen. Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota, Sen. Henry “Scoop” Jackson of Washington, and Gov. George Wallace of Alabama – proved familiar but uninspiring. In the midst of this drab battle for the soul of the Democratic Party, Thompson spots an honest man in a pack of party hacks: Sen. George McGovern of South Dakota.

McGovern, who died last weekend at the age of 90, emerged in 1972 as the Democratic Party’s unlikely presidential nominee. As a rare liberal spokesman from a conservative state, McGovern championed the anti-war movement in the U.S.

Senate. McGovern, a former history professor and decorated World War II bomber pilot, passionately protested the Vietnam War on the Senate floor, lamenting: “I am sick and tired of old men dreaming up wars for young men to die in.” McGovern’s fledgling campaign picked up steam through the primaries of 1972, and Hunter S. Thompson went along for the ride.

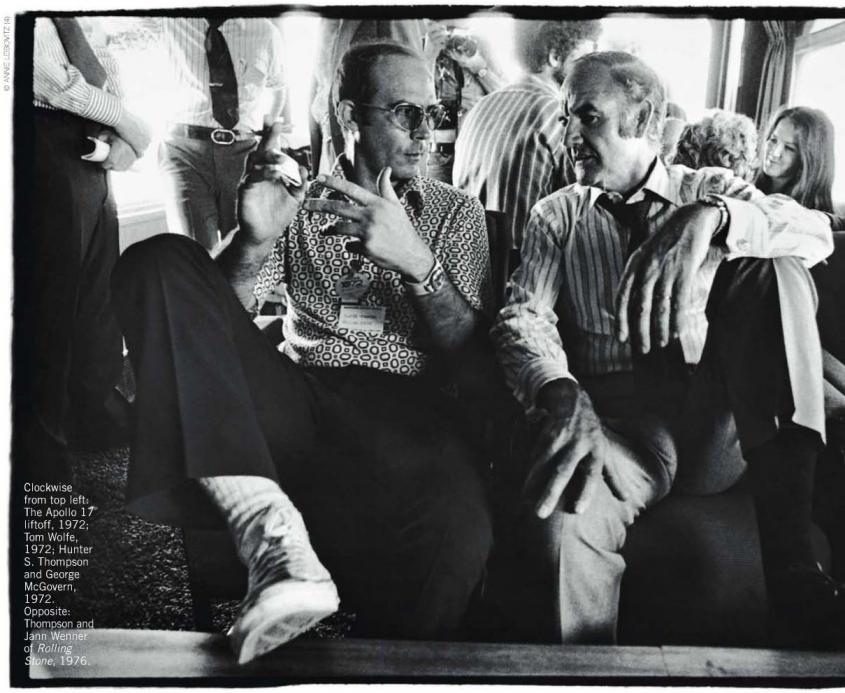

Hunter S. Thompson (left) and Sen. George McGovern on the campaign trail, 1972. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

As a sort of embedded journalist with the McGovern campaign, Thompson shunned the idea of impartial reporting. Objective journalism, he argued, is a “pompous contradiction in terms.” After all, selecting sources and choosing verbs are subjective activities. Besides, Thompson reasoned, artificial objectivity blinded most journalists to the dishonesty of politicians like Richard Nixon, his main antagonist. By this reasoning, Thompson publicly declared his support for McGovern early in the primaries.

At times, Thompson’s irreverent style (which he termed “Gonzo journalism”) also blurs the line between fiction and reality. On the campaign trail, he reported that a rumor was circulating that frontrunner Ed Muskie had been treated with a powerful psychoactive drug called Ibogaine. His report was true. There was indeed a rumor, but Thompson had started it himself. Similarly, Thompson sets his sights on derailing Hubert Humphrey’s nomination bid. Over the course of a brutal series of primary battles between Humphrey and McGovern, Thompson tells of suspected election fraud and attempts to circumvent the newly-instated primary system by the “old ward heeler” from Minnesota.

From the primaries to the convention, Thompson’s colorful prose proves both gripping and darkly humorous. The unprecedented access he gained to McGovern campaign staffers and Democratic Party chiefs enabled him to document every day of the historic contest in graphic detail. Thompson does not simply regurgitate press releases and the transcripts of pool interviews. He vividly relates the feel of life on the campaign trail – the blind euphoria, the hopeless despair, the money, the loneliness, the alcohol, and all. Thompson’s clarity and wit have firmly established Fear and Loathing as a celebrated work of political journalism and its author as an icon of American literature.

But what of the hero? What of George McGovern?

McGovern lost every state in the Union, save for Massachusetts and the District of Columbia. Nixon’s landslide victory represented the first time a Republican carried every Southern state and delivered the incumbent a then-record 520 electoral votes. Thompson rattles with contempt in his reflections on the Nixon landslide but maintains enough composure to analyze the reasons for McGovern’s devastating loss. First, the ugly primary fights with Humphrey left the liberal McGovern labeled as the candidate of “Amnesty, Acid, and Abortion.” Second, the fractured Democratic establishment never fully united behind its nominee.

Perhaps most significantly, McGovern’s running mate, Sen. Tom Eagleton of Missouri, was revealed to have undergone electroconvulsive therapy for depression. After waffling for days, McGovern asked Eagleton to step down to be replaced by former Peace Corps director Sargent Shriver. Through these debacles, Thompson portrays McGovern as an honest man making foolish mistakes. These political errors undermined public confidence in McGovern’s judgment and reinforced his image as “too liberal” for the country.

While the American public rejected McGovern in 1972, Thompson viewed him as the last best hope for America. As he writes: “The tragedy of all this is that George McGovern, for all his mistakes […] is one of the few men who’ve run for President of the United States in this century who really understands what a fantastic monument to all the best instincts of the human race this country might have been.”

In light of the social upheaval of the 1960s and the persistent trauma of war in Vietnam, McGovern’s grassroots campaign provided a powerful contrast to the heavy-handed and often secretive Nixon Administration. Indeed, as Thompson tracked McGovern’s campaign for Rolling Stone, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein diligently investigated the June 17, 1972, Watergate burglary in the pages of the Washington Post. To avoid a probable impeachment, Nixon resigned the presidency just over two years later. As Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72 brilliantly reveals, George McGovern inspired many with a vision of an honest and humane government intent on building peace at home and abroad. It is a vision that has been eroding ever since.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.