This week the National Association of Scholars released a report critical of the ways US History is taught at the University of Texas at Austin and at Texas A & M. The authors of the report, entitled, “Recasting History: Are Race, Class, and Gender Dominating American History?” claimed to have studied all sections of lower-division US History courses taught at the two universities in all 2010. They concluded that:

“all too often the course readings gave strong emphasis to race, class, or gender (RCG) social history, an emphasis so strong that it diminished the attention given to other subjects in American history (such as military, diplomatic, religious, intellectual history). The result is that these institutions frequently offered students a less-than-comprehensive picture of U.S. history.”

In other words, the stated goal of the NAS is to ensure that introductory, required courses in US History are broader and more comprehensive. But the study was so poorly researched and its conclusions are so flawed, that one is forced to ask whether the goal was simply to attack the teaching of histories that include race, class, and gender.

As Editor of Not Even Past and of our sister site, 15 Minute History for K-12 teachers and students, one of my main concerns is to balance the kinds of history we offer to the public, so I am automatically interested in a study that examines such an important set of university courses. As the report points out, since 1971, students at public universities in Texas are required to take two courses in US History. The purpose of the requirement was always political and contemporary: to produce citizens who have at least a rudimentary knowledge of the history of the country where they live and vote. (Whether required university courses can do that is a debate for another day.)

It is tempting to dismiss the report as just another conservative critique of the liberal academy. For decades, politically conservative sectors of the public have been calling for us to offer a less critical view of US History and a focus on what they see as the positive elements of our past. They often claim, as the NAS report does (p. 49), that teaching about race, class, and gender has politicized the teaching of history, while teaching more political, economic, intellectual, and military history would depoliticize it. In these assessments, social and cultural history are depicted as either trivial or as left-leaning, while political, military and intellectual history are seen as important and politically neutral. The NAS report attempts to mask that critique by claiming to call for all-inclusive courses:

“A depoliticized history would provide a comprehensive interpretation of American history that does not shortchange students by denying them exposure to intellectual, political, religious, diplomatic, military, and economic historical themes.”

But this call for a “broad” approach — which is favored by people on all sides of the issues — follows from the conclusion that:

“The root of the problem is that colleges and universities have drifted from their main mission. They and particular programs within them, increasingly think of themselves as responsible for reforming American society and curing it of prejudice and bigotry. When universities and university programs consider it necessary to atone for, and help erase, oppressions of the past; one way in which they do so is by depicting history as primarily a struggle of the downtrodden against rooted injustice.”

As a university professor, I consider it a primary part of my job to teach students to read carefully, to learn to understand multiple sides of any historical issue, and to draw conclusions based on the documents they read, rather than on the assumptions they bring to class. The NAS report fails to do all of those things. If a student turned in this study to a college level course, I suspect they would be asked, at the very least, to rethink the questions they are asking and to do more research.

The methods used to study the US History courses are deeply flawed. The problems with the methodology are most apparent at the very beginning and the very end. The statement quoted above, that “colleges and universities…think of themselves as responsible for reforming American society,” is not a conclusion drawn from study of courses taught, but an assumption that the authors brought to the project. There is nothing in any of the syllabi or assignments that this study examines that leads to that conclusion. We teach students to ask open-ended questions so they don’t end up simply finding evidence to prove what they believed all along. The question “Are race, class, and gender dominating American History?” is designed to be answered “yes.” (A better question would be: “what role do race, class, and gender play in teaching US History?”) The authors, not surprisingly, “found” only evidence that supported their assumptions. The most important kinds of evidence in doing any research are the documents that challenge our assumptions, because that evidence forces all of us to think harder about whatever we study and to defend our ideas more persuasively.

The assumptions underlying the study are themselves problematic. There is no history that is politically neutral. Anyone who pays any attention to the decisions of the Supreme Court or any debate in Congress must realize that the Constitution itself is a political document that can be interpreted in multiple, conflicting ways. Teaching the important political, intellectual, and economic documents of our history, which we all do already, adds to the politicization of History teaching, if those documents are read carefully and discussed openly.

More important, the authors of this study relied on superficial and misleading evidence about what goes on the classroom. As others have now pointed out, the absence of the Declaration of Independence or the Gettysburg Address from the syllabus does not mean that those documents are not being discussed in the classroom. And as UT History Professor Jeremi Suri said in his response to the report, one cannot teach political or military or economic history in any meaningful way without teaching race, class, and gender.

One of the most important lessons we can teach students about history is to examine any subject in its full context. Every document, whether the Bill of Rights or a personal letter from a soldier to her mother, has to be understood in context. But the authors of the NAS study didn’t visit a single classroom or interview a single professor. They didn’t open themselves up to finding any evidence that challenged the assumptions with which they began. The purpose of research is not necessarily to change one’s mind about a subject, but to learn more about it, to see the past in a more complex way, with more possibilities for interpretation and outcome. When we do research that confirms what we already knew, or leaves us with another simplistic either/or picture of the world, we haven’t learned anything at all.

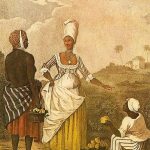

If we look at the issues raised in the NAS report in historical context, we learn that the teaching of race, class, and gender in history today is a corrective to the way history was written and taught before the Second World War. No one liked history that’s “all names and dates,” especially when all those names represented the people with power. When historians began studying racial minorities, women, workers, and people at the bottom of other hierarchies, they discovered a much richer story. They discovered that we can’t understand the US Civil War if we don’t know anything about slavery, and we can’t understand slavery if we don’t study the life experiences of slaves as well as slave owners—men and women both. We can’t understand economic and technological progress if we only study the people who benefited from change and we can’t understand military or diplomatic history if we only study generals, diplomats, and presidents.

Most important of all is that the NAS report fails to recognize that we already teach the introductory surveys they are asking for: broad studies of US History that include the major political, economic, and military developments as well as the intersection of the powerful people who make policy and the lives of ordinary people. History is a complicated, messy experience that produces triumphs and tragedies, large and small.

There are always ways we can improve what and how we teach. Instead of this familiar debate about political vs social history, I wish we were talking about how we can activate student learning in the classroom like Mills Kelly does here or William Turkel does here, or how we can use smart, focused internet projects to engage students with online activities they already enjoy, as The Pew Internet Project reports here. But mostly, I wish NAS had sent their researchers here to our classrooms, where our professors are winning teaching awards for using innovative techniques, or our offices and hallways and meeting rooms where we talk to each other every semester about teaching.

The National Association of Scholars claims to want broader, more inclusive courses in US History, but since we are already teaching broadly and including the topics they ask for, and since their report seems designed to prove the opposite, one can’t help but suspect that the real goal of this report is to swing the pendulum all the way back to a study of history that erases the discussion of class, gender, and race, from the curriculum. We are not going there.

The NAS Report:

Recasting History: Are Race, Class, and Gender Dominating American History?

Responses:

Jeremi Suri, What Kind of History Should We Teach?

Joseph Adelman, The Value of Studying Politics in Context

University of Texas at Austin Statement on National Association of Scholars Report

Responses posted on the NAS website

Texas Tribune article on the NAS report

Another excellent response by blogger Historiann, “A Dumb and Dishonest View of American History Education in Texas.”