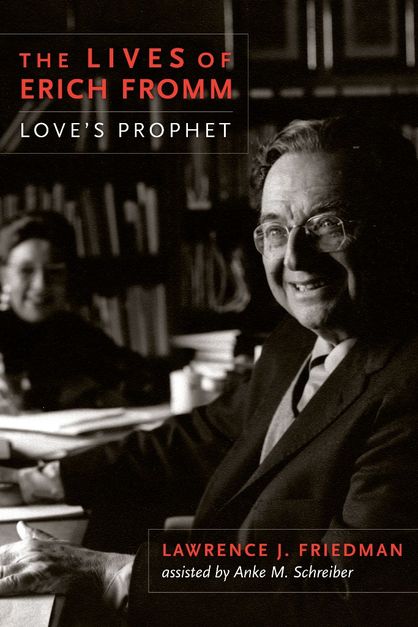

Perhaps one day some whimsical people with money will get together and honor books for their subtitles. Lawrence Friedman’s new biography of Erich Fromm, subtitled “Love’s Prophet,” wins for getting the total picture; for, in just two words, capturing a whole life. But it couldn’t have been a difficult choice.

Erich Fromm was a German-American psychotherapist and ethicist, most noted within the academy for his groundbreaking synthesis of Marxism and Freudianism. After emigrating from Germany in 1934, Fromm became a robust public intellectual, a voice for love and freedom who spoke in words a schoolchild could read. Fromm’s message was brief: love — and don’t wait — or perish. Mike Wallace’s interview with Fromm perfectly captures his otherworldly charm, his preference for the elegance of plain truth over reasoned facts, his will to enjoy, his deep concern for humanity, his long view of history. This footage makes me nostalgic for the time when playful intellectuals visiting us from some mystical other world would come on TV.

Fromm’s ecstatic prophetic pose alienated many academics.and few young scholars today are familiar with or even interested in Fromm’s arguments about freedom, fascism, capitalism or love. And yet, there was something about Fromm’s style that seemed to catch; few thinkers achieved Fromm’s global popularity.

Fromm’s ecstatic prophetic pose alienated many academics.and few young scholars today are familiar with or even interested in Fromm’s arguments about freedom, fascism, capitalism or love. And yet, there was something about Fromm’s style that seemed to catch; few thinkers achieved Fromm’s global popularity.

In Friedman’s telling, Fromm wasted no time becoming Fromm. The biography opens with an adolescent Fromm’s coming-to-terms with his neurotic, overbearing father.. Rather than moving far from his home in Frankfurt to become a rabbi, as he wished, Fromm remained close to his family by attending the nearby University of Heidelberg. There he studied economics under Alfred Weber, Max Weber’s brother. Fromm’s dissertation explored “the function of Jewish law in maintaining social cohesion and continuity in the three Diaspora communities – the Karaites, the Reform Jews, and the Hasidim.” Much of his ethics would follow from these roots in humanistic Judaism. Although Weber believed Fromm’s work qualified him for a promising career as a scholar, Fromm’s father wasn’t so sure. He showed up in Heidelberg on the day of his son’s defense to tell the faculty committee that, because Erich was not prepared and would fail, he was going to kill himself.

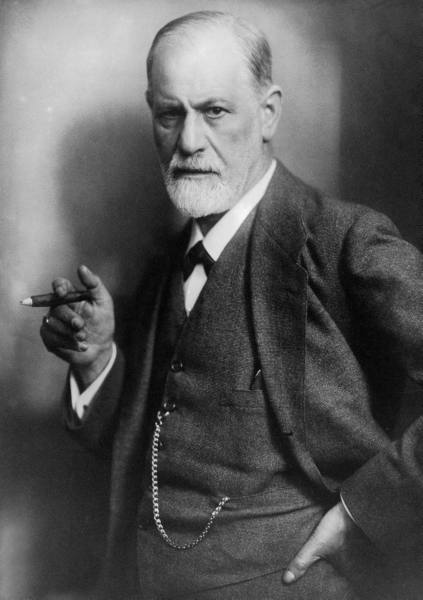

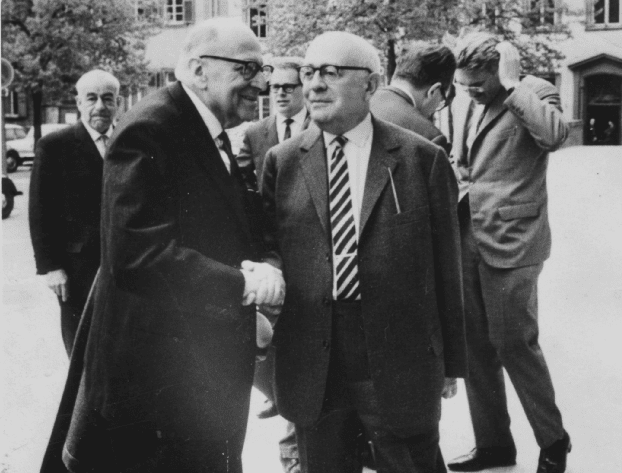

Fromm’s affair with Frieda Reichmann, a much older Frankfurt psychoanalyst who introduced him to the new discipline and thereafter become his first of three wives, offered the emotional exit he needed from his oppressive family. Fromm spent his twenties invigorated by psychoanalytic training, and even then, he showed signs of departing from Freudian orthodoxy. Around 1929, Max Horkheimer of the Frankfurt School for Social Research hired Fromm to bring in the new psychology that had been blossoming in Vienna and Berlin. For whatever reason, Fromm’s estrangement from the Frankfurt School casts a large shadow over the magnitude of his involvement, first in grounding the Institute’s particular “Freudo-Marxism,” and secondly in ensuring its future. Many scholars and activists today, historians included, have become so accustomed to thinking about culture in fluid social psychological terms similar to those Fromm pioneered that they forget the great chasm that once existed between Orthodox Marxism and Freudian analysis. Fromm worked to forge a dialectical link between “social structure” and “instinctual need,” where structures (e.g. forms of work organization, distributions of wealth, broad cultural practices) modified libidinous impulses that in turn cement or challenge (“explode”) those structures. Fromm proved that psychoanalysis could provide Marxism with a better understanding of subjectivity and he “postulated that the entire interaction between changing instincts and changing social forms took place most conspicuously within the family, the primary mediating agency between the individual psyche and broad social structures.” At Frankfurt, Fromm accomplished what was then a radical philosophical feat.

When Hitler came to power, Fromm was offered a position on Columbia’s sociology faculty. Fromm successfully lobbied Columbia for the Frankfort Institute’s use of University facilities in Morningside Heights, ensuring the future of an intellectual tradition he would not long remain part of. Fromm’s intellectual conflict with some of the Frankfurt School crew (notably Adorno and Marcuse), at least on the surface, revolved around his departure from the notion, popularized by Freud, that sexual libido, in its repression by the reality principle, was the material basis of the unconscious and of mental illness. In America, Fromm cultivated friendships with analysts who shared his rejection of Freud’s libido theory of mind. Through his friendships with Karen Horney, Harry Stack Sullivan, and Margaret Mead, who all emphasized culture and intersubjectivity over the economic and the psychosexual, Fromm’s thought flourished. Rather than seeking to occupy a position of authority or submission vis-a-vis his contemporaries, Fromm wove his own ideas out of the “interpenetrative,” fraternal exchanges with his rather intelligent and pioneering friends. In other words, the generative mode of his life’s work corresponded gracefully to its content.

Fromm’s psychotherapeutic career occupies in my opinion too small a portion of Friedman’s book, though we can forgive the biographer this fault since access to that deeply private history is no doubt heavily restricted. What we do know is that Fromm was a lay analyst, which created problems for him in an increasingly institutionalized, medical and behavioralist psychological field. Fromm innovated his technique away from what believed were Freud’s alienating and paternalist approaches; hence his rejection of the couch. The way Friedman describes it, Fromm viewed therapy as a “dance” between friends, and his sessions recall a piece by the performance artist Marina Abramovic, “The Artist is Present,” in which two interlocutors stare at each other, taking the other in, silently and fully, affirming their shared experience and desires.

On the question of politics, Friedman argues that Fromm must be remembered as an enthusiastic Marxist. Fromm called himself a socialist humanist, but if his commitment to Freudianism was often contested, so were his Marxist credentials. The fuss was understandable: Fromm confounded ideologues, especially with such seemingly innocuous ideals – love, self-discovery, freedom. When Herbert Marcuse published Eros and Civilization, in 1955, with its rabid critique of Neo-Freudianism, Fromm’s split with Frankfurt returned to haunt him. Marcuse’s apparent victory in what became a highly publicized feud in the American magazine Dissent seemed to seal Fromm’s rejection by Marxist scholars and the New Left: by Marcuse’s rhetorical tricks, Fromm’s post-Freudianism came, oddly, to signify his post-Marxism. What Marcuse saw in Fromm’s good tidings – his evangelical message of love (formalized a year after Eros in The Art of Loving – in my opinion Fromm’s most beautiful book) – was the happy acceptance of bourgeois alienation, a “sunny-side up” accommodation to capitalism akin to the opium of religion and capitalist morality. Yet, despite his deep spiritualism,or because of it, Fromm vigorously criticized American religious life, which he believed combined the worst of authoritarian and consumerist moral delinquency. America’s God appeared to Fromm as, in his words, the “remote General Director of the Universe, Inc.” If wit is cunning simplicity, Fromm’s flew over Marcuse’s head. Friedman’s verdict of what Fromm actually believed should be definitive: “Society had to be changed, to be sure, but the reader [of Fromm] should not await the demise of capitalist structures and values before seeking to master the art of loving.” Fromm’s revolution was impatient, so impatient that it transformed into what we call ethics — an under-acknowledged aspect of Fromm’s Marxism, a bedfellow, perhaps, to Walter Benjamin’s cry that “the state of exception is now.”

In 1961, Fromm’s cousin Heinz Brandt, a radical social democrat who survived the Death March, was kidnapped in West Berlin by Stasi operatives. Just as Fromm had worked tirelessly to assist a large network of Jewish friends, relatives, and colleagues escape Germany before and after Kristallnacht, Fromm now entered into a game of international arm wrestling that involved Bertrand Russell and Khrushchev. His cousin was released by the GDR, no doubt in part due to Fromm’s skillful manipulation. On these occasions, Fromm personally displayed the courage in the face of state brutality he so cherished in his writings.

Friedman’s biography leaves little wanting. I highly recommend it, especially as a readable primer in Critical Theory. Excepting his mild tendency to repeat himself, Friedman has produced what will surely remain the best intellectual biography of Fromm . Sadly, however, if we happily accept Fromm’s ordainment as prophet, this designation must remain strictly a stylistic observation. One sociologist recently penned an article on Fromm called “How to Become a Forgotten Intellectual.” Although Fromm’s books sold extremely well throughout the postwar years and over the globe, he failed to develop a mass following appropriate for a prophet. Here’s to hoping Friedman’s book reignites at least some interest in a man who failed at every turn to be uninteresting.

Photo Credits:

Sigmund Freud, 1922 (Image courtesy of LIFE Photo Archive)

The central figures of the “Frankfurt” school: Max Horkheimer (front left), Theodor Adorno (front right), and Jürgen Habermas (in the background, right), 1964, Heidelberg (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

A plaque memorializing Fromm, Bayerischer Platz, Berlin (Image courtesy of Axel Mauruszat/Wikimedia Commons)

Images used under Fair Use Guidelines