by Kyle Smith

Amilcar Shabazz has authored an intriguing account of the fight against Jim Crow segregation in higher education in Texas. First he reviews the struggle of the descendants of African slaves to obtain the right to higher education in Texas from the time of Reconstruction to the 1940s. Then he provides a compelling and detailed description of the battle waged by national and state civil rights organizations to end the accepted system of segregation that denied blacks admission to colleges and universities in the southern United States. He argues that it was not primarily the collective action of the organizations or the government that brought about integration:

Crow segregation in higher education in Texas. First he reviews the struggle of the descendants of African slaves to obtain the right to higher education in Texas from the time of Reconstruction to the 1940s. Then he provides a compelling and detailed description of the battle waged by national and state civil rights organizations to end the accepted system of segregation that denied blacks admission to colleges and universities in the southern United States. He argues that it was not primarily the collective action of the organizations or the government that brought about integration:

“That triumph must be found in the self-determined struggle of blacks themselves… It was the brave example of black students, who, from 1949 to 1965, stepped onto white campuses in the face of white resistance that ranged from passive, to massive and legal, to illegal mob violence. These students played the decisive part in winning the hearts and minds of large numbers of blacks of all social classes and, eventually, of many white liberals to integration as the only way to ensure racial equality and justice.”

Shabazz does a masterful job compiling original sources, including the NAACP Papers now housed in the Library of Congress, state and federal government documents, personal correspondence, personal interviews, and decisions of the Courts that heard the desegregation cases of the 1950s. The author expertly weaves this data into a moving and enlightening narrative of the era and what he calls the “University Movement.” Shabazz chronicles this “Movement’s” early ideological and financial struggles, and its victories and losses in the struggle against racism and discrimination in higher education on Texas.

Shabazz provides his readers a compelling picture of the efforts of the ex-slaves and their descendants to achieve the benefits of the freedom granted by the Emancipation Proclamation and the Thirteenth through Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution. With as much urgency as slave owners fought to keep their slaves uneducated and illiterate to maintain power over them, blacks sought to obtain the education they realized held the key to equality and independence. From the outset, the Reconstruction governments set up schools and provided for higher education of the freed blacks. But by the end of Reconstruction, new state legislatures throughout the south had reversed the legislation that had given rights to blacks, including funding for higher education. Supported by the 1896 Supreme Court Ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson, the Texas Legislature established the separate and woefully unequal education system that existed for the next three-quarters of century. This provided blacks one institution of higher education, the Texas A&M branch called Prairie View. It was not until the Supreme Court’s ruling in Sweatt v. Painter that the state was forced to make an attempt to at least look like they were attempting to provide equal access to higher education for black Texans. Sweatt v. Painter made it illegal for the state to maintain separate and unequal institutions of higher education. Between 1949 and 1952 at major universities like the University of Texas and at private denominational colleges like Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary, the walls of segregation were torn down as blacks gained a new era of opportunity and equality in higher education.

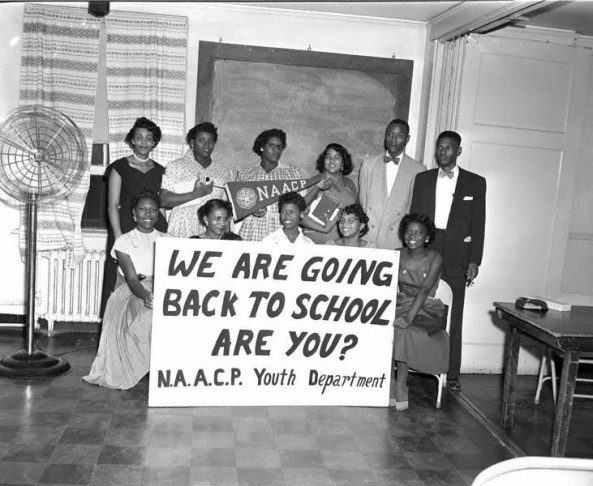

Members of the Texas NAACP Youth Department (Image courtesy of the UT Center for American History)

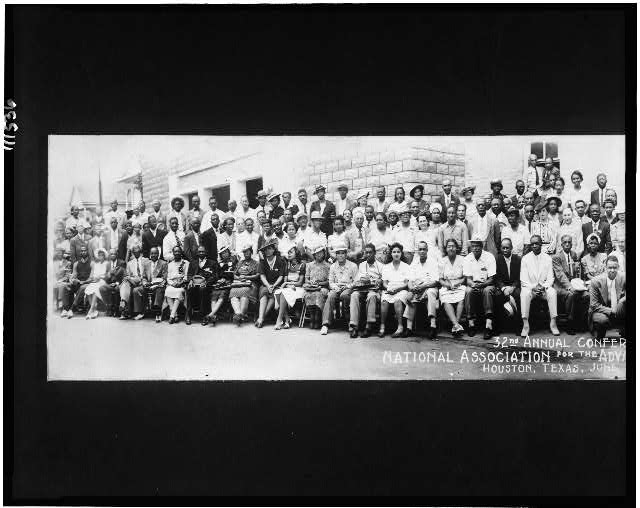

Attendees of the NAACP’s annual conference, Houston, Texas, June 24-28, 1941 (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Shabazz emphasizes the role played by the individual students who dared to lead the fight by followed. Heman Sweat is undoubtedly the most famous, as the first African American admitted to the UT School of Law, and because of the lawsuit bearing his name. Not so well known, but just as important to the fight to integrate Texas higher education was Herman Barnett, the first black student to integrate the University of Texas Medical School. John Chase has the distinction of being the first student admitted to graduate school for architecture at UT. Hattie Briscoe was the first black woman admitted to St. Mary’s University Law School in San Antonio. Shabazz conveys their amazing courage and the reasons their their contributions are well worth preserving. Any student of U.S. history and especially anyone interested in twentieth century African American history will enjoy this highly readable and enlightening volume.

All images used under Fair Use Guidelines