By Blake Scott

Our eyes travel from the sea’s surface to a palm-tree shore. A female voice can be heard. “I am Cuba,” she tells us. “Once Christopher Columbus landed here. He wrote in his diary: ‘This is the most beautiful land ever seen by human eyes.’ Thank you, Señor Columbus.”

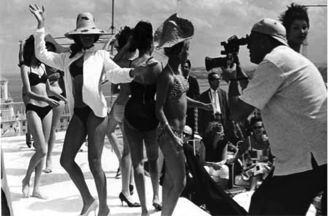

An extravagant party on the rooftop of a Havana hotel. It’s the late 1950s; hedonistic tourism is booming in the City. A band plays loud. Drinks. Laughter. Our line of vision moves from the hotel’s rooftop to a crowd of tourists below, where we see a woman and follow her into the pool. Underwater.

Three male tourists from the U.S. sit at a table in one of Havana’s decadent clubs. They order drinks:

“Another daiquiri.”

“Give me a scotch, make it a double.”

“Vodka dragon.”

The waiter asks, “something on the side maybe?”

One of the men lowers his dark sunglasses. “I’ll take that tasty morsel.” And his friend, “And I’ll take that dish.” The men embrace as two beautiful yet sad-faced women walk over from the bar to their table. “Nothing is indecent in Cuba if you’ve got enough dough,” he tells his friend.

These deeply metaphorical scenes open the first of four episodes that make up the 1964 film, Soy Cuba (I am Cuba). Hailed today a classic for its inventive cinematography, I am Cuba was virtually forgotten for three decades. After a week in theaters in Cuba and the Soviet Union, the film went into the archives: one copy in Moscow and another in Havana. This essay reviews I am Cuba’s production and revival.

The Art of Cold War

The exchange of weapons, sugar, and communist dogma has traditionally dominated U.S. understandings of the Soviet-Cuban alliance. I am Cuba represents another aspect to this relationship. During the Cold War, Cuba was much more than a strategic island 90 miles from the U.S. border. For idealists in the Soviet Union, the Cuban Revolution offered hope for progressive socialism. The young bearded revolutionaries in the Sierra Maestra Mountains reenergized intellectuals who were tired of the old guard politics in their own country. Soviet poet and co-writer of I am Cuba, Yevgeny Yevtushenko, says he was “childishly happy” when the Cuban Revolution triumphed. He remembers, fondly, Russian parents naming their sons “Fidel.”

During this early moment of optimism, the Soviet Union sent a film commission to meet representatives from the newly formed Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC). The rebels founded ICAIC just three months after entering Havana. Film and art were to become key components in Cuba’s effort to create a new revolutionary culture. The Institute’s first director, Alfredo Guevara, explains that during the Soviet commission’s visit, “They proposed to make a movie… about its solidarity and friendship with Cuba, expressing how they sympathized with the Cuban Revolution.” ICAIC and the Soviet Union’s Mosfilm Studios agreed to collaborate on a film about the island’s dramatic transition from corrupt republic to revolutionary state.

The Soviet commission recommended Mikhail Kalatozov to direct the project. At the time, Kalatozov was one of the most famous filmmakers in the Soviet Union. His film, The Cranes are Flying, won the Palme d’Or at the 1958 Cannes Film Festival. He was one of the few Soviet directors whose work had been widely viewed by audiences in the West. For the Cuban project, Kalatozov invited Sergey Urusevsky, his cinematographer from The Cranes are Flying and also The Letter Never Sent (1959), to be Director of Photography. Young Soviet poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko and Cuban author Enrique Pineda Barnet were selected to write the script. I am Cuba was the first film produced by this Soviet-Cuban partnership. During production on the island the film crew received the full support of the Cuban revolutionary government. When Kalatozov needed 5,000 extras for a battle scene – to offer just one example – 5,000 Cuban soldiers were mobilized to play the part.

The Cuban Revolution had sparked hope, but also tension with the U.S. In 1961, the CIA sponsored an invasion at the Bay of Pigs. The following year, President Kennedy ordered a naval blockade after U-2 surveillance planes discovered nuclear missile sites. It was the closest the U.S. and the Soviet Union ever came to nuclear war. Cuba was right in the middle of it and so was the film crew of I am Cuba. The production team had become part of the Cold War. Kalatozov announced to the press: “I’ll make a movie in Cuba that will be my answer, and that of the whole Soviet people, against the naval blockade, this cruel aggression of American imperialism!”

The resulting film is an epic poem; a surreal critique of realities suffered before and confronted during the revolution. Kalatozov and his team sought to capture events as they unfolded, from social injustice to glorious revolt. Produced over a fourteen-month period, from 1962 to 1964, the film embodies the creativity, the militant optimism, and also the naiveté of the era. It is both Cold War history and revolutionary art.

Storyline and Reception

After the opening vignette of Havana’s immoral tourist scene, the film transitions to the story of a poor farmer. He works his entire life in the fields. He is old and tired, but the rich Cuban soil provides. He is happy enough, until a greedy landowner arrives with two armed guards and informs him that the land has been sold to United Fruit. “Now you’ll be able to rest,” the owner tells him. The landowner is a vendepatria elite (someone who sells out his country to foreign interests). The farmer is dispossessed and heartbroken. At the end of the episode, the female narrator asks, “Who will answer for this blood?”

The third and fourth parts of I am Cuba move away from the forms of capitalist exploitation (hedonist tourist parties and land-grabbing) to revolutionary mobilization.

Students and young people organize against the dictatorship and U.S. imperialism. When U.S. sailors chase a frightened woman, Gloria, a young student stands up against their belligerence. Other acts of defiance follow. The once passive student becomes a martyr, and more students take to the streets.

In the final part of the film, the nonviolent hands of a peasant turn to revolutionary action. He is left with no choice but to join Fidel and the revolutionaries in the Sierra Maestra. They charge heroically into battle. “To die for your motherland is to live.”

Kalatozov and Urusevsky thought they had made a classic, but the audience didn’t agree. The film premiered simultaneously in Moscow and Santiago de Cuba, and then disappeared. Brazilian filmmaker Vicente Ferraz offers some possible answers for this short theatrical run in his 2005 documentary I am Cuba, the Siberian Mammoth. Ferraz interviewed crewmembers about their experiences making the film. They explained, in short, that the Cuban audience “felt insulted.” The characters seemed to react mechanically to structural circumstances, like pawns in a revolutionary chess game.

Sergio Corrieri, who played a student-revolutionary in the film, recalled people saying, “This really isn’t our reality. This character doesn’t exist, it isn’t Cuban . . . it was the Cuban reality seen through a Slavic prism.”

The film’s poetic tone and surreal mood, conveyed by highly mobile camera movement, connected poorly with Cubans who faced dangerous realities. In the middle of food shortages, and with U.S. military planes flying overhead, the Russians presented them with an unrealistic film. Enrique Pineda Barnet, Cuban co-writer, remembered the premiere with regret. “It was terrible. The first thing that bothered me was that voice, that text: ‘I am Cuba.’” The true story of the revolution, in the minds of many Cubans, had been subordinated to the cinematographic ambitions of the Soviet filmmakers.

The film was also unfavorably received in the Soviet Union, but for different reasons. The U.S. presence in Cuba was considered too glamorous for Soviet sensibilities. Pre-revolutionary Cuba looked like too much fun. Meanwhile, in the U.S., the film was never allowed to reach an audience because of its communist ties. I am Cuba was boxed-in by the polemics of the Cold War.

Revival

Only with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War, some thirty years later, did I am Cuba reemerge. It was U.S. filmmakers, ironically, who first came to love and promote the Soviet-Cuban production, which so bitingly critiqued U.S. culture. The film’s path from obscurity to classic is not entirely clear. But, in brief, social status and money pushed the film into public light. Directors Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola saw I am Cuba and became the film’s biggest supporters. Distribution rights were acquired from Mosfilm Studios, and in 1995 the film was formally released in the U.S.

Scorsese and Coppola, along with other filmmakers, admired I am Cuba for the very reason it was initially discarded: the radical form and cinematic style, which seemed to overshadow its revolutionary content. Contemporary film critics have praised I am Cuba as a masterpiece in cinematography. In several key scenes, the camera travels vertically from ground level, or from a rooftop, to another space of events (below or above), and then moves horizontally through windows and interior rooms, all in a single take. “There is a shot near the beginning of I Am Cuba,” explains Roger Ebert, “that is one of the most astonishing I have ever seen.” Every image is like a piece of art inside a larger work.

With this post-Cold War revival, the film’s original “flaws” are still acknowledged, but the value system is inverted. The script is still considered weak – “propaganda” – but that is now seen as acceptable because the cinematography is so beautiful. But is the quality of I am Cuba’s story really so secondary to its style? Does the film not capture aspects of truth despite, or even because of, its surreal presentation? Sometimes the “imaginary,” as writer André Breton once put it, can be the most “real.” While it’s true that the film offers subjective and often exoticized representations of reality, there is still something real in them. I am Cuba’s content cannot be dismissed as mere propaganda. The film is a window, among other things, into Cuba’s revolt, Cold War militancy, and also Soviet views of the American tropics.

For those of us interested in the relationship between history and cinema, I am Cuba’s plot and its story of production merit further analysis. How might the film change, for example, our understandings of the tenuous relationship between Cuba, the Soviet Union and the U.S.? Why was the film rejected so abruptly in the mid-1960s, and beloved so quickly in the 1990s? Narrow visions of acceptable revolutionary art? Capitalist society’s infatuation with the cultural ruins of communism? I am Cuba has as much to say about history as it does about film technique.

In the current moment of state-promoted luxury tourism, I am Cuba may also help us understand the complicated relationship between the Cuban Revolution’s past and present. Most Cubans living on the island have never seen I am Cuba. The film’s depiction of pre-revolutionary tourism, however, looks a lot like the bar and club scene of Havana today.

To learn more about the film I am Cuba, and the historical context in which it was produced:

• I am Cuba, The Siberian Mammoth. A documentary by Vicente Ferraz about the making of I am Cuba. Ferraz returns to Havana after the film’s revival to interview cast and crew about their experiences on set. The interviews are fascinating. A must see. Here’s the trailer.

• Week-end in Havana. An exotic, carefree view of pre-revolutionary Cuba by U.S. filmmaker Walter Lang. To watch this film alongside I am Cuba is to see Havana from two dramatically different viewpoints. Here’s the trailer.

• History Will Absolve Me. Fidel Castro’s powerful speech against the Batista dictatorship in 1953. The speech outlines the justifications for the July 26th Movement. It marks the beginning of a long drawn-out rebellion.

• On Becoming Cuban: Identity, Nationality, and Culture. Professor Louis A. Pérez Jr.’s book highlights the historical relationship between Cuba and United States. He meticulously explains the cross-cultural context that directly led up to the Cuban Revolution.

• The Cuban Revolution: Origins, Course, and Legacy. Professor Marifeli Pérez-Stable’s book provides an in depth analysis of the socio-economic causes and effects of the Cuban Revolution.

More films about life in Cuba’s revolution:

• Memories of Underdevelopment. The story of Sergio, a bourgeois writer who decides to stay in revolutionary Havana, even though his wife and friends flee to Miami.

• Lucía. The film traces the lives of three Cuban women, each named Lucía from three different historical periods: the Cuban war of independence (with Spain), the 1930’s, and the 1960’s.

• Strawberry and Chocolate. The story of a complicated friendship between a young communist student and a gay artist in 1979 Havana. The film offers a powerful critique of authoritarianism and homophobia in the revolution.

• Suite Havana. In this documentary, we follow the lives of ten Cubans as they go about their daily routine. The film has no dialogue, using only sound and image.

Photo Credits:

Scenes from the film I am Cuba

Images used under Fair Use Guidelines