Earth has warmed by over one degree Celsius since the pre-industrial period, and computer models suggest that human emissions could lead to another two degrees Celsius of warming by the end of the twenty-first century. The combination of the speed, eventual magnitude, global impact, and human origin of present-day warming has no parallel in Earth’s history. Yet natural forces have long transformed the climates in which human populations struggled to survive. For over a century, “climate historians” have attempted to uncover how populations responded to those changes.

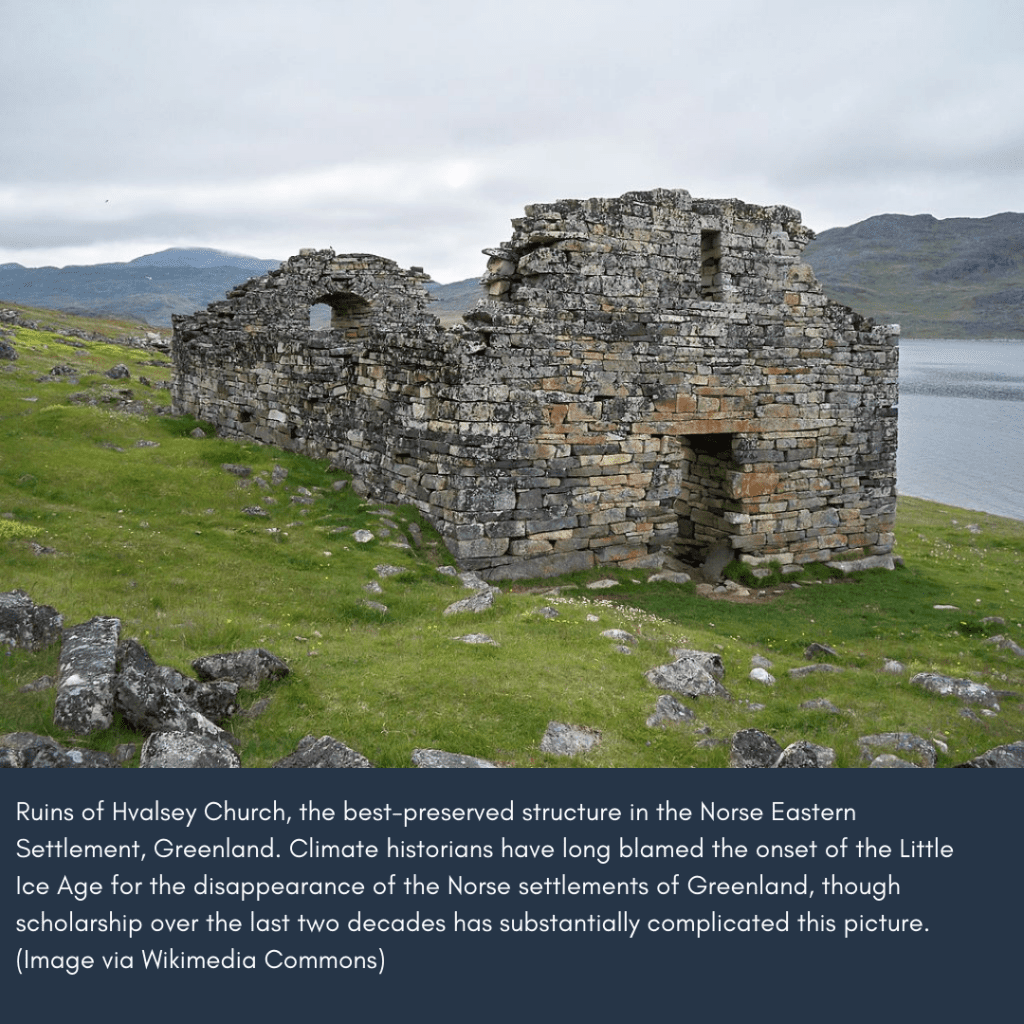

Climate history as a field has been dominated by studies that use statistical or qualitative methods to link these harvest failures to food shortages, famines, outbreaks of epidemic disease, and conflict within or between societies. Some of the most influential books and articles written by climate historians conclude that sustained periods of cooling or drying caused some of history’s best-known civilizations to “collapse” – to rapidly lose political organization, socioeconomic complexity, and ultimately population.

Other studies assert that even many civilizations that escaped collapse during periods of cooling or drying still endured sustained subsistence crises that culminated in political transformation. In some accounts, crises could undermine entire continents, in the fourteenth or seventeenth centuries, for instance, when tens of millions perished. In all this scholarship, the worst-affected civilizations were those with subsistence strategies, hydraulic infrastructure, military or demographic pressures, and inefficient or unpopular governments that left them vulnerable to environmental disruption.

Many climate historians study the past not only to enrich historical scholarship, but also to learn lessons that may inform efforts to plan for the future. Indeed, climate history now informs some of the direst predictions for humanity’s future, including the common assumption that present-day civilizations would disintegrate if global heating exceeds dangerous thresholds.

Yet in recent decades, archaeologists have uncovered striking evidence that hunter-gatherer communities and early agricultural settlements endured and exploited climatic shocks similar in magnitude – if not in origin – to those anticipated in some of the most alarming projections of future warming. A new generation of climate historians has also criticized the methods and assumptions common to most accounts of crisis and collapse in complex civilizations, particularly those of the Common Era.

Studies now reveal that even populations – especially Indigenous populations – once used as examples in narratives of climate-driven crisis in fact found ingenious ways to respond to new environmental realities. The traditional focus on societal catastrophe by climate historians today seems less like a reflection of past reality, and more like a distortion caused by selection biases that privilege periods of agricultural disruption in agrarian empires.

Climate historians therefore increasingly explore the resilience of past communities and societies to climate changes and anomalies. That term – “resilience” – today has many definitions and many critics, who argue for example that it can either hide the socially constructed power dynamics most responsible for vulnerability, or privilege macro-scales of social analysis where profound disruption rarely occurs.

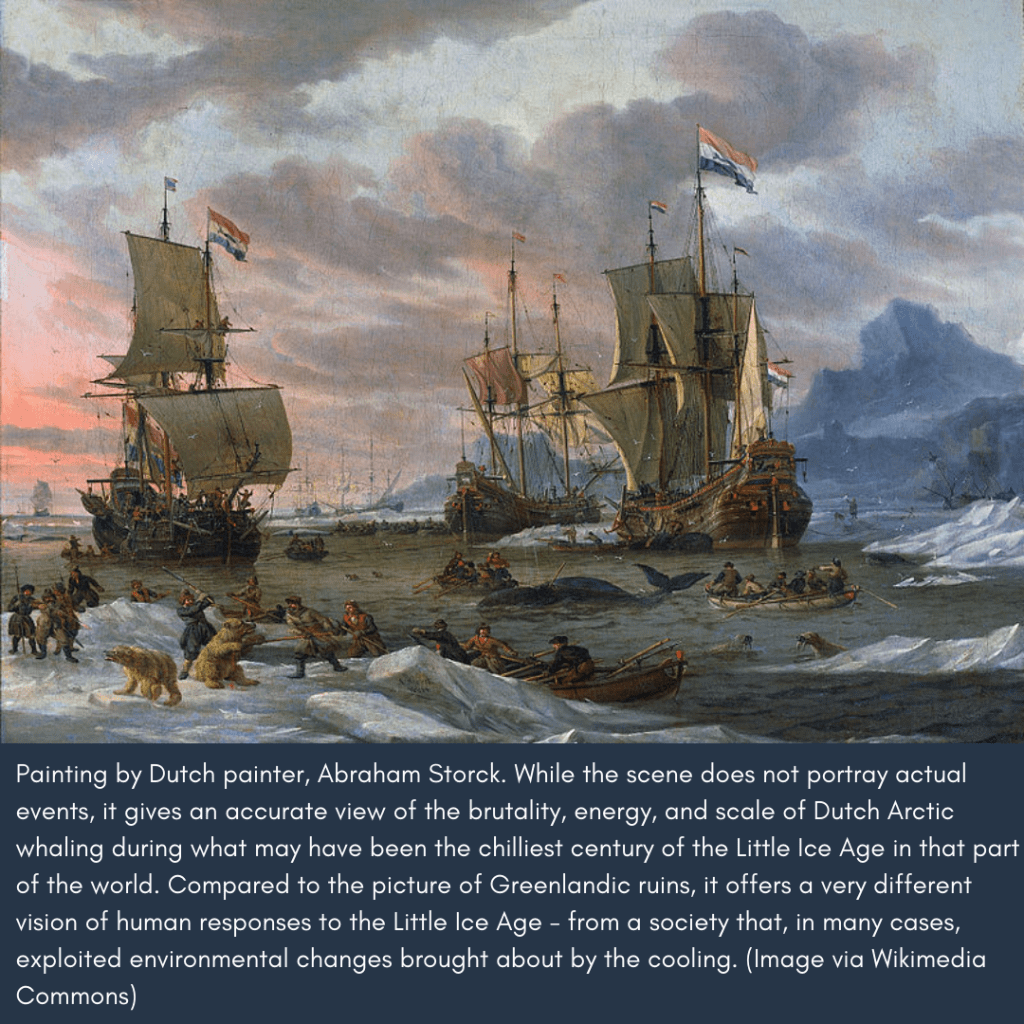

Yet a broad definition of resilience that emphasizes power dynamics and distinguishes between change across different scales in time and space is providing a powerful tool for climate historians. Resilience encourages us to cast our gaze away from the agrarian empires and abstract associations between human and climatic histories that have long dominated climate history. It compels historians to, for example, explore social responses to climate changes on local scales, to uncover ingenious responses to shifting environmental circumstances, and to explain how resilience for some came at a cost to others.

Resilience, in short, is helping us craft more complete accounts of the past – and, just maybe, helping us learn valuable lessons for the future.

Dagomar Degroot is an Associate Professor of History at Georgetown University and an environmental historian who bridges the humanities and sciences to explore how societies have thrived – or suffered – in the face of dramatic changes in the natural world.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.