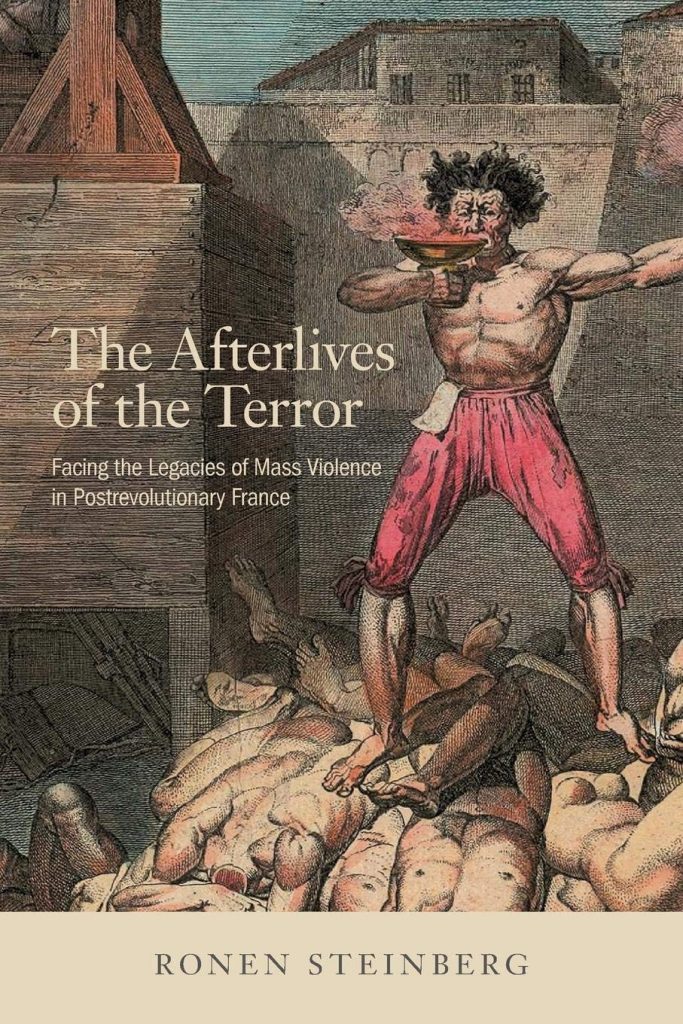

The Afterlives of the Terror: Facing the Legacies of Mass Violence in Postrevolutionary France. By Ronen Steinberg. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2019. 240 pp. $19.95.

Between 1793 and 1794, the Jacobin Club, a leftist political organization led by Maximilien Robespierre held political power in France. Via this medium, the Jacobins, as they came to be known, enforced a radical understanding of the revolutionary values of the French Revolution through mass violence. This episode is known simply as “the Terror”. In 1794 the Jacobins were forced out office in an episode called the “Thermidorian Reaction”, after which everything seemed to show what the Terror was a thing of the past. In The Afterlives of Terror. Facing the Legacies of Mass Violence in Postrevolutionary France, Ronen Steinberg challenges this assumption and argues that this episode stretched beyond the years of its occurrence in the form of debates and practices aimed towards overcoming this modern form of national trauma.

Did the Terror really pass if public opinion and popular practices were engaged in discussing and overcoming the Terror itself? Informing his argument with contemporary theorization of violence developed mainly by Holocaust studies, Steinberg applies the contemporary categories of “trauma” and “transitional justice” to this episode and analyzes the social practices that aimed to make sense and reconcile violence with the new social life that sprung from it. Examining them through these concepts, he shows how the need to overcome collective trauma was as prevalent then as it is now. Steinberg thus presents the Terror as a historic episode that extended well beyond its material events as it invaded the discursive realms of memory and time. In studying this invasion, he shows how pervasive the recent past continued to be even after the events themselves had passed, making an argument for continuity in historical temporality.

Steinberg’s book engages with this inquiry through five case studies which function as the structural division of the book. Chapter 1 studies the semiotic crisis debated through public opinion on the events of the Revolution. It focuses on the inability of the existent language to refer to the new events and thus introduces the invention of new concepts, such as “terrorism” and “the Terror” itself. Chapter 2 analyzes the trials held as part of the Thermidorian Reaction to public officials who were in charge of enforcing mass violence during the Terror. In order to do so, he applies the concept of “transitional justice,” which sheds light over how revolutionaries dealt with their recent past. Chapter 3 engages with les biens des condamnés, petition records mostly done by women claiming for restitution of property as victims of the Terror, exemplifying what Steinberg sees as a desire to reestablish the past prior to the onset of violence. Chapter 4 studies the mass graves as material remains of the violence and the way in which people, family, and society reconfigured their lost ones and in turn their lives through their exhumations and searching parties. And finally, Chapter 5 analyzes the Phantasmagoria theatrical spectacle as a representation of the ghostly past that haunted the present of revolutionary France. By engaging with these case studies, the readers will both learn of the events of the Terror and the Thermidorian reaction whilst finding themselves surprised to see how much these debates actually mirror ours when facing the repercussions of violence. Since the author frames his historical research using contemporary concepts that present-day societies apply to violent episodes on a mass scale, the discussion on conceptual innovation, official trials, restitution, mass graves, and commemoration, all practices that are currently being performed around the globe, rings closer to home than what the reader may originally expect from this publication.

A final note. If the readers were to be convinced by this recommendation and decided to engage with the book, they need not be concerned about what may seem at first sight as an anachronistic application of contemporary concepts to an episode so far away in history. On the contrary, the application of these categories’ sheds light on the malleability of historical time and of historical studies in general. Steinberg’s writing is strong and clear and paints an accurate picture of one of the most contested and studied events of the French Revolution. Overall, The Afterlives of Terror comes across as a highly stimulating read as well as a refreshing contribution both to this historiography of French revolutionary studies and to our present-day anxieties on mass violence and trauma. Readers can be certain that this book will both challenge and expand their knowledge of this episode while also keeping them fully engaged.