Joint Editor’s note: Like so many cities, Austin is in a process of rapid transformation. To better understand this moment and its consequences for the city’s residents, we can draw on insights from other places and periods. This review is the first in a new series called The State of the City. The series, which is a collaboration between Urbānitūs and Not Even Past, aims to share insights from the latest research as well as classic books that explore the varied lives of cities and the connection between urban development and globalization.

Paris – Capital of Modernity, by David Harvey, 2006, 230 pp, Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group

The rule of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte was bracketed by two violent revolutions in the French capital: the Revolution of 1848 and the Paris Commune of 1871. Elected as president in 1848, he staged a coup three years later and, like his famous uncle, anointed himself emperor of the “Second Empire.” Bonaparte amassed an enormous amount of political and financial power, which he proceeded to unleash onto the city of Paris, transforming the physical landscape and Parisians’ experiences of time, space, neighborhood, and identity.

Beginning with the double-entendre in its title, Marxist historical geographer David Harvey’s Paris, Capital of Modernity emphasizes both the role that capitalism played in thrusting Paris into modernity and the fact that the radical re-envisioning and restructuring of the City of Light heralded urban transformations around the globe over the next century.

Paris, Capital of Modernity self-consciously positions itself as a counterpoint to Karl Marx’s famous class analysis of the 1851 coup, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. Marx, writing in 1852, focused on the political and class machinations that ultimately led to the betrayal of French laborers by the bourgeoisie. Harvey takes the analysis a step farther. He argues that 1851 demarcated two fundamentally different visions for the city: one bourgeois, founded on the rights of individuals but even more on rights of private property; the other, a socialist vision that aimed to alleviate the dire poverty and dismal working and living conditions of the laboring classes.

The economic crisis of 1846-1847 that precipitated the revolution had resulted in over-accumulations of both capital and labor. The coup of 1851 resulted in a concentration of power in the executive. Conditions were therefore ripe for the new prefect, Baron Georges Haussmann, to embark on a massive public works program. How, Harvey asks, did capital and finance, labor, municipal politics, community identity, and the compression of space and time act upon each other during the Second Empire and lead toward the bloodshed of the 1871 Commune?

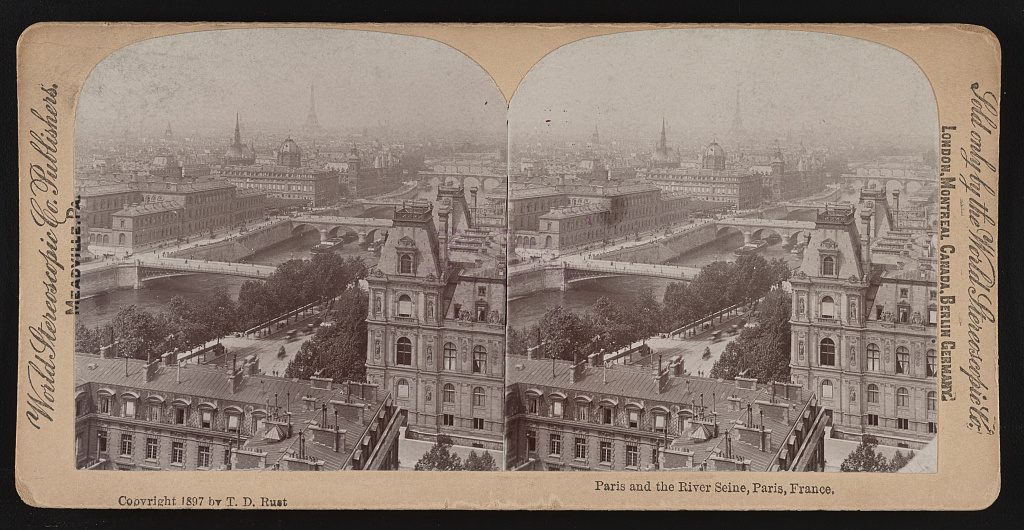

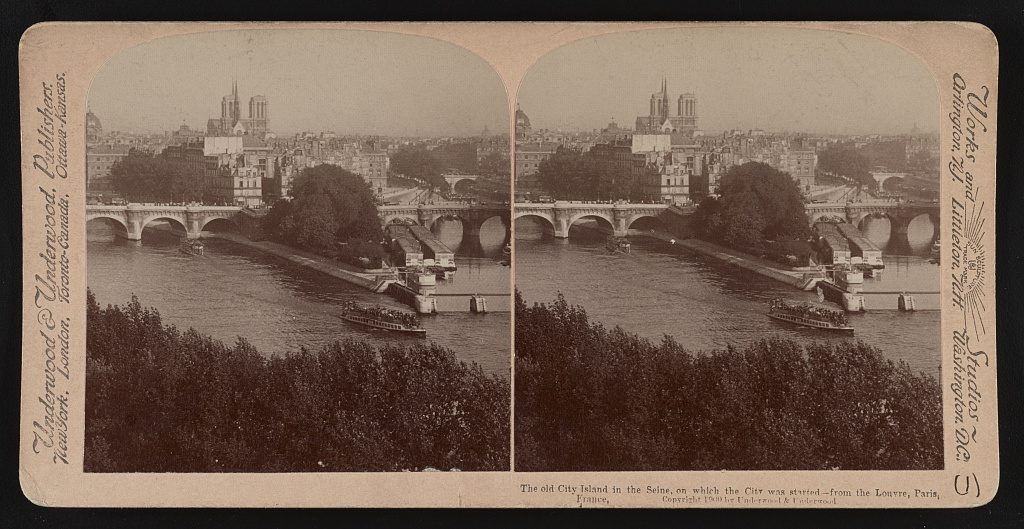

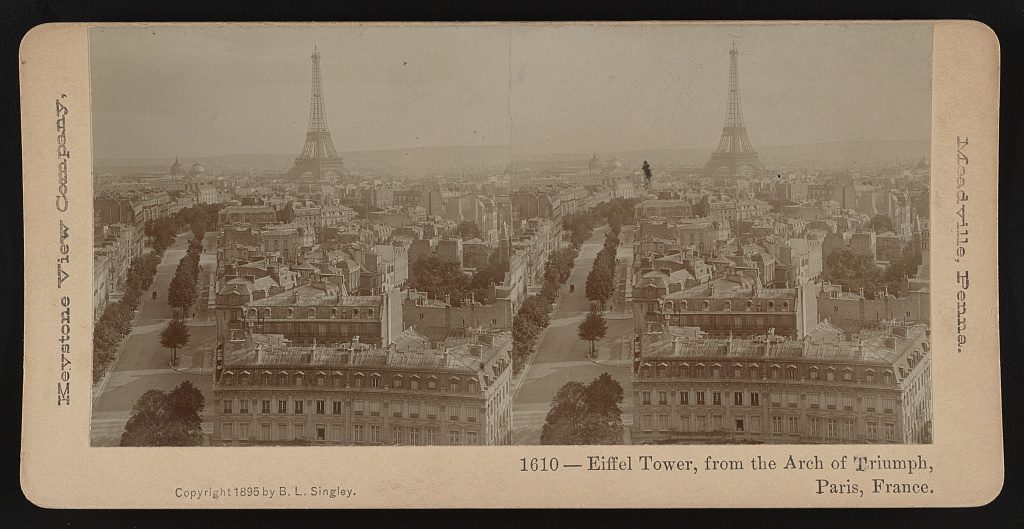

With the use of dubious but effective financing mechanisms, Haussmann procured the capital to purchase both the necessary political power and construction labor for his projects. He bulldozed many of the city’s narrow medieval streets and replaced them with the grands boulevards, parks, and vistas that we know today. Haussmann’s projects pushed money throughout the city and pulled labor into it from the provinces. The construction of railroads, public transportation, and communication systems accelerated the flow of people and information and drastically shrank the amount of time it took to travel around and into Paris, creating a new geography of experience and imagination.

Capitalism and social mobility transformed the landscapes inhabited by the upper classes, providing the space for sidewalk cafés and large, showy department stores—an explicitly consumerist and “extroverted urbanism.” Meanwhile, workers migrated into the metropolis in huge numbers. However, foreshadowing the spatial homogenization of American cities (including Austin!) sixty years later, the poor were displaced to the periphery in a push-pull cycle. As industrial land use was moved from the center, the workers followed. At the same time, they were pushed out by the demolition of their neighborhoods and the astronomical rise in rents. Whereas before they shared buildings with the higher-income bourgeois, they were increasingly socially segregated and fragmented. Before 1848 Paris had been fairly heterogeneous; after Haussmman’s reconstruction, it was increasingly polarized into wealthy western and poor, more radical eastern neighborhoods, such as Belleville.

This reinforced a new dynamic in local politics. Haussmann and Bonaparte refused to allow Paris to have a municipal government and devolved responsibilities to the city districts, or arrondissements. As a result, Parisians across the city developed an anger toward the national government and increasingly identified with their neighborhoods as a site of belonging.

France’s catastrophic loss during the 1870 Franco-Prussian War ended Bonaparte’s reign and the Second Empire. The national government fled to the small city of Tours, and a radical, socialist, and locally sourced Parisian government stepped into the power vacuum and assumed control over the city. This commune lasted for exactly two months and became the model for Marx’s concept of a “dictatorship by the proletariat.”

Harvey’s analysis leads almost too neatly and inevitably to the violence during the Commune and the bloodshed that followed when the national government and army recaptured the city and massacred the communards. While the number of victims, ranging from seven to thirty-five thousand, continues to be fiercely debated (Harvey claims thirty thousand), what is clear is that the vast majority were from the working classes and their supporters. The bourgeois horror of public disorder—particularly, any that threatened their property—amplified by the increased social polarization, resulted in a racialized ideology directed at workers that went beyond the pathologizing of previous decades and permitted the degree and speed of violence against them, including against women.

Both The Eighteenth Brumaire and Paris, Capital of Modernity conclude in their final pages with the toppling of the imperial column in the Place Vendôme and the statue of Napoléon Bonaparte (dressed as Julius Caesar) on its top. In Marx’s 1852 book, this act of symbolic violence against a capitalist empire was a prophetic vision of an event Marx could only imagine, while Harvey recounts the actual toppling of the column twelve days before the Commune collapsed. “Between the prediction and the event,” Harvey declares, “lay eighteen years of ‘ferocious farce.’” Three years after the bloodshed and conflagration, the column was re-erected along with the nation’s colonial ambitions, but the burned-out shell of the Tuileries palace, France’s last royal residence, was torn down. The disparate fate of these monuments embodies the unresolved contradictions left in the wake of the Second Empire at the dawn of the Third Republic.

Isabelle S. Headrick is a PhD candidate in history at the University of Texas at Austin. She works on the global modern education movement and its interaction with Iranian, Jewish, global French, and family histories. Specifically, her research focuses on a family of French-educated, Jewish school directors who lived in Iran for seventy years (1908-1978) and worked during that time for the Alliance Israélite Universelle, a transnational Jewish educational organization. Her article, “A Family in Iran: Women Teachers, Minority Integration, and Family Networks in the Jewish Schools of the Alliance Israélite Universelle in Iran, 1900–1950,” was published in October 2019 in The Journal of the Middle East and Africa. Her work has been supported by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute and the Schusterman Center for Jewish Studies and Center for European Studies at UT-Austin. Prior to entering the history program, Isabelle worked for fifteen years as an affordable housing non-profit director and developer in Austin with organizations that serve people with disabilities, people experiencing homelessness, seniors, and families with children.

For more articles from Urbānitūs see here. This review was first published in February 2020 on Not Even Past and is reprinted here with new illustrations.