From the editors: We are delighted to republish this moving profile of Alberto Torres Fuster (1872-1922) by Emilio Zamora. Dr Zamora was recently awarded the Roy Rosenzweig Distinguished Service Award from the Organization of American Historians. See our profile of Dr Zamora’s remarkable career here.

We remember the departed for many reasons, but we mostly wish to revisit the memory of persons who left deep impressions among us. We may also want to commemorate the achievements and values of public figures that have given much to our communities. The Museums and Cultural Programs Division (MCP) of the Austin Parks and Recreation Department reminded us recently that we also invoke such memories as researchers seeking to better understand and appreciate the past.

I was fortunate that Ms. Laura Esparza, manager of the MCP, asked me to participate in such a memorialization on October 9 and 10, 2020 entitled, “All Together Here: A Community Symposium for Discovery and Remembrance.” The online forum convened 40 scholars, community activists and city staff to bring attention to recent archeological work at Oakwood Cemetery and to pay our respects to the many who have come before us. I participated in Panel 7, “Many Histories, One Burial Ground,” moderated by Gregg Farrar, with my colleagues Dr. Daina Berry from the University of Texas and Dr. Theodore Francis II of Huston-Tillotson University as fellow presenters.

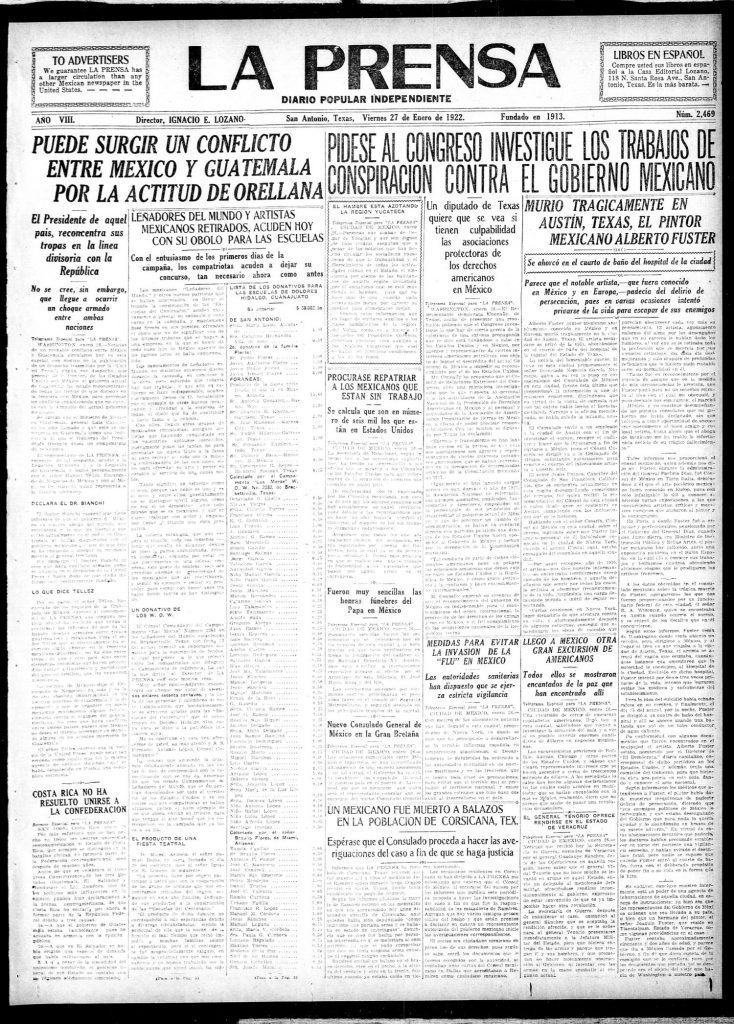

Since I wanted to bring attention to the Mexican community, I searched the Spanish-language newspapers for burials at Oakwood during the turn of the century. I had no special purpose in mind other than to find a significant case that would help me contemplate funerary practices among Mexicans in Austin at the time. I found one in the San Antonio daily of La Prensa on the passing of a 50-year-old Mexican National named Alberto Torres Fuster (1872-1922). He was not from Austin but died in an Austin hospital while on his way from New York to Mexico.

Fuster was born in Tlacotalpán, Veracruz. By the age of sixteen, he had completed studies in painting at Mexico City’s prestigious Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes and obtained a government stipend to study art in France and Italy. Fuster distinguished himself as an artist of the modernist school and secured special recognition at the 1900 Paris Exposition. While in Italy, he also served as a Mexican consulate official for fourteen years. Fuster returned to teach and paint in Mexico City during the early 1900s. He received government support to study and paint in New York beginning around 1919.

Despite his major achievements, Fuster was not well. Although there are no clear records on the cause of his illness, an official explanation was that he had lost trust in the goodness of humanity and became distraught over his haunting anxieties. Sadly, while on his way to Mexico, Fuster attempted suicide at the Austin train station. Someone rushed him to a local hospital and, although the staff kept a constant watch over him, Fuster hanged himself on January 31, 1922. Within days, Mexican government officials made funeral arrangements through the General Consulate Office from San Antonio. At least 250 Austinites, including Mexican government officials, socially prominent Mexicans representing organizations from throughout Texas, and local residents who wished to pay their respects laid Fuster to rest at the Oakwood Cemetery Annex.

We can only imagine what members of the largely working-class Mexican community must have thought as they contemplated why such an accomplished and respected person would decide to end his life. Then as now, understanding such a personal act of finality may be impossible. Fuster’s passing, however, may have especially bedeviled the poorer Mexican observers. They lived with pains associated with the denials and indignities of racial segregation and other forms of discrimination. Their trauma must have seemed just as unbearable, but many of them persevered somehow.

This is not to minimize mental illness, but rather to ask instead why the largely poor Mexicans, as well as African Americans, did not succumb in greater numbers to self-destructive impulses. Their sense of responsibility to family and community may have allowed their demons to pass through them; much like soldiers in combat who have transcended the horror of war by imagining their return to the love and safety of home. It is sad to consider that no such psychological relief helped Fuster, evidenced in the deep sense of anguish and suffering that led to his death in a faraway place from his home in Mexico.

To continue with our use of the sociological imagination that C. Wright Mills suggested long ago, the outpouring of condolences offer other cultural scripts, or views, of the Mexican community of Austin in the early 1900s.

An unnamed Baptist Church held religious services prior to the burial, indicating that Mexicans also embraced the promise of salvation through faith as Protestants in a small community of mostly Catholics. The participation of Mexican government officials and organizations of mostly Mexicans Nationals as well as the overwhelming use of Spanish underscored cultural diversity and an attachment to Mexico and things Mexican. This does not mean that the Austin Mexican community was mostly Mexico-born. Most, if not all Mexican communities in Texas were U.S.-born at this time. Personal choice and the isolation that came with segregation, on the other hand, explains their pan-Mexican identity.

After the burial, the congregation gathered at the hall of a benevolent organization, La Sociedad Union y Beneficencia Mexicana, located at 707 Colorado Street, in an area west of the Freeway that they no longer inhabit because the city council ordered their segregation (along with African Americans) to the east side of the city in 1928.

Representatives of La Cruz Azul Mexicana, a statewide organization akin to the Red Cross, and the Comisión Honorífica Mexicana, another statewide organization affiliated with the Mexican consulate offices, also participated in the ceremonies. Lauro Izaguirre, the head of the Mexican consulate in San Antonio, gave the eulogy at the cemetery and led a vigil at the hall. He spoke about Fuster’s “imposing” personality and his “exquisite” art exhibited in Europe, Mexico, and the United States.

María Hernández, a major Mexican leader representing La Cruz Azul and the Comisiónes Honoríficas from Texas, introduced Izaguirre. She was followed by officers and members of other organizations, including Pedro E. Gonzalez, the president of the of the Sociedad, and Aureliano García, J. G. Perales, T. G. Ortiz, Sritas Adela y Olivia Garcia Refugio de la Cruz and Sras Juana de Galván and Bartola García. Years later, the Mexican community from Austin gave Fuster another send-off when the Mexican government exhumed his remains and reburied them at El Panteón Tepeyac in Mexico City.

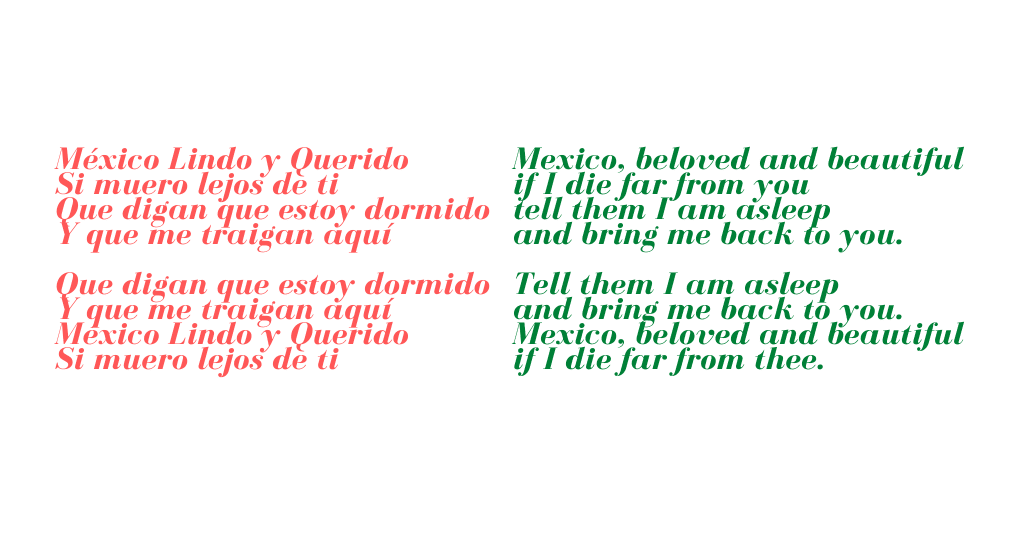

Fuster’s return fulfilled the longing for home expressed in México Lindo y Querido, the sentimental song that became the unofficial anthem of Mexico coincidentally composed by Jesús Monge Ramirez in 1921.

Fuster is now a memory, recovered from a largely dismissed and forgotten Mexican past. His passing also provides us a small window through which we may remember a life whose status and accomplishments accentuate the reduced standing of a growing working-class community of approximately 4,000 Mexicans that similarly lived and died in the 1920s. Despite these differences, the great equalizer that death is, brought him to rest at Oakwood, reminding us all of life’s vicissitudes.

Alberto Fuster, QPD.

This profile was first published here.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.