Encouraged by the conference theme, “We Shall March Forward Together,” over 100 affiliated Texas school districts and four-hundred people registered for the 23rd annual meeting of the Mexican American School Boards Association (MASBA) in San Antonio that took place on September 9-12, 2021. Hundreds more enjoyed the collegial fellowship and a robust program of vendor exhibitions, a Board of Directors meeting, school visits, keynote presentations, panel speakers, and discussions, a Mariachi demonstration and performances, 9-11 observances, a dance, scholarship announcement, recognitions and awards ceremonies. Coming out in bold, yet cautious, defiance of COVID-inspired fears that inhibit gatherings in the midst of a pandemic, MASBA has travelled a long and often challenging road since 1970 when Dr. José Cárdenas, the intrepid educator, school administrator, and founder of the Intercultural Development Research Association (IDRA), proposed the idea of such an organization and became a founding member of MASBA, along with Blandina “Bambi” Cardenas (Austin), José Angel Gutiérrez (Dallas), Rubén Hinojosa (McAllen), Gus García (Austin), Chris Escamilla (San Antonio), Amancio Chapa (La Joya), and Ciro Rodriguez (San Antonio).

At the time of its founding, Mexican American youth attended some of the poorest and most segregated schools in the state and, partly as a consequence, registered strikingly low attainment levels, high retention and dropout rates and few prospects for advancement into colleges and universities. They also had few adults in positions of influence that could speak on their behalf. Around 400, or 4 percent of school board members in the 1,400 Texas school districts, were Mexican Americans. Encouraged by the Mexican American social movement for dignity and equal rights, including numerous student walkouts demanding an end to discrimination and a more relevant and effective learning environment, a growing number of Mexican Americans began to vie for positions in local school boards. Successful redistricting and school desegregation suits by the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, also encouraged Mexican American participation in improving the educational experience of their youth. The Justice Department also entered the picture by filing a suit against Texas that generated several desegregation cases involving Mexican Americans as an ethnic group and language minority.

More than fifty-five years after the founding of MASBA, Mexican American youth have made significant improvements in their educational standing. Their educational position relative to other groups, however, remains relatively unchanged in 2020. This includes the persistent problems of attending some of the most poorly funded schools and registering some of the highest dropout rates and lower graduation percentages, as well as relatively lower college enrollment figures and college completion rates. These problems are magnified by the high growth rate of the Mexican American school age population and their inability to close the educational attainment gap with their higher achieving peers from other groups. Although they constitute more than 50% of the public school population, they only make up less than 37% of students enrolled in higher education institutions. The attainment deficit, relative to other groups, has mostly remained unchanged in the last ten years and may continue into the foreseeable future.

The current state of Mexican American education—improved group standing alongside a poorer record of achievement relative to Anglo youth—speaks to the continued need for an active and effective MASBA and explains the resolve of its membership and leadership to continue advocating for much needed change. Judging from the stirring keynote speeches, inspirational performances, engaging presentations and the animated response from the membership in attendance, the generational hope that an educated and self-conscious youth can lead Mexican American communities into a better future endures as a historical motivation in MASBA. My observations on the conference activities focus on the events that I attended and observed.

Mariachi performances were a highlight of the conference. This should not surprise anyone who knows that MASBA was instrumental in convincing the University Interscholastic League to incorporate the Mexican musical form and ensemble of the Mariachi into its statewide program of student recognition. High school mariachi groups—the Mariachi Espuelas de Plata from North Side, Fort Worth ISD, and the Mariachi Diamantes Estelares of Judson ISD—regaled the audience during the Friday and Saturday morning breakfasts. Dr. Richard A. Carranza, the former superintendent of Houston ISD and the New York City Schools Chancellor—as well as a Mariachi music performer himself—later led a performance and demonstration of mariachi music with the accompaniment of the famous Mariachi Campanas de America, the pride of San Antonio. They featured the various instruments in the ensemble and the different kinds of music that Mariachis perform during the Saturday lunch. Dr. Carranza and the Mariachi concluded their special event with a presentation and serenading of Dr. Angela Valenzuela, upon her recipient of the coveted Campana Award for public service.

Louis Q. Reyes, a past President, former Executive Director, and now Ambassador of MASBA received the grand Golden Molcajete Award, a recognition of exemplary service to the organization. Though not accorded the fanfare given to the Campana Award recipient, his acknowledgment was equally significant.

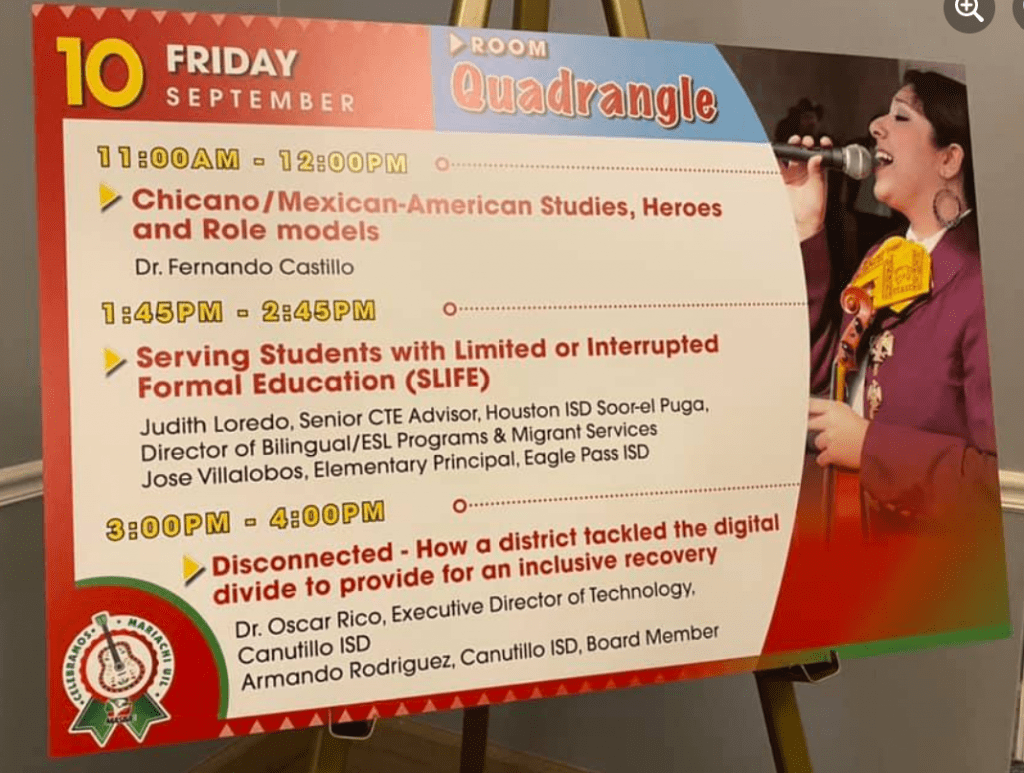

The heart of the conference, twenty-three panels—provided conference participants with opportunities to hear presentations and participate in conversations on current issues of importance. The themes and topics were as follows with the number of panels listed in brackets: Ethnic Studies (6), Educational Programs (4), Professional Development for Teachers and Board Members (4), Advocacy (1), Critical Race Theory (1), Energy Conservation in the Schools (1), Equity (1), Health Concerns (1), Legislation (1), School Taxes (1), School Infrastructure Issues (1), and The Digital Divide (1).

MASBA conference planners most probably gave preference to Ethnic Studies because the organization has long supported expanding the state’s curriculum to include the history and culture of under-represented groups, particularly Mexican Americans. The large number of groups involved in sponsoring teacher development workshops, curriculum writing projects, and Ethnic Studies advocacy efforts before the State Board of Education and the Texas Legislature may have also submitted the largest number of panel proposals. The recent attention that the Texas Legislature gave to a failed Ethnic Studies bill (House Bill 1504), as well as to the controversial Senate Bill 3 passed during the second special session of the Texas State Legislature that discourages the teaching of race and that the governor signed into law, may also explain the focus on Ethnic Studies.

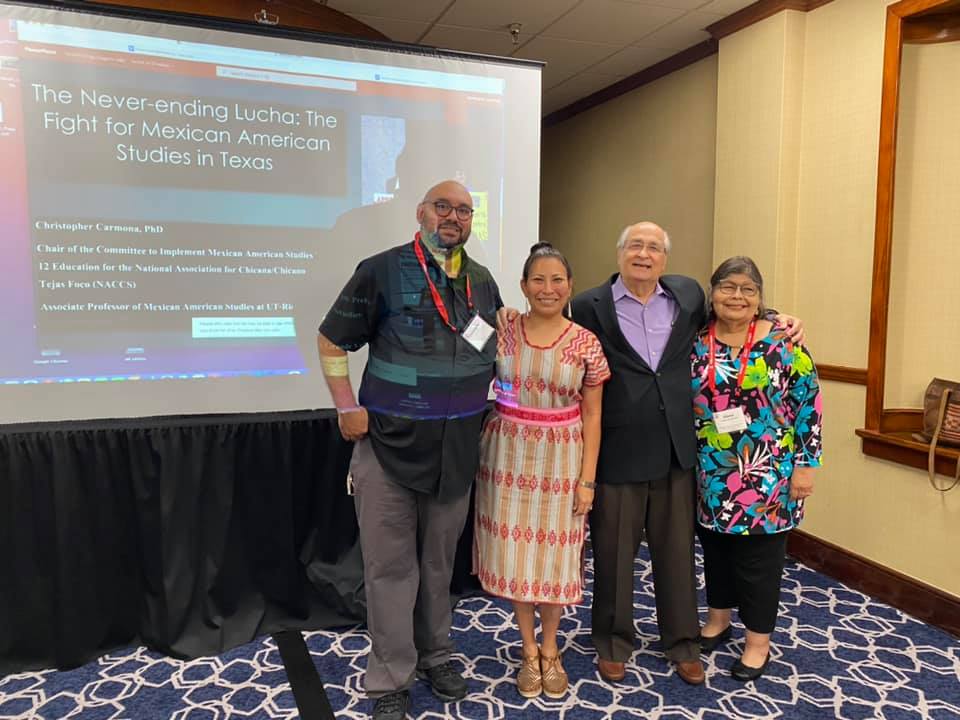

One session on Ethnic Studies stood out in particular. Representatives of the IDRA, the Teachers’ Academy from the University of Texas at San Antonio and an officer of the Pre K-12 Committee of the NACCS Tejas Foco (or chapter affiliate of the National Association for Chicana and Chicano Studies) described their work in a statewide campaign of well over 30 collaborating organizations and institutions. Their purpose is to expand the curriculum and prepare teachers to teach Ethnic Studies, including Mexican American Studies, and to justify these research-based initiatives as successful models for academic success for youth of all racial and ethnic groups, albeit especially for Mexican American public school students in Texas whose numbers represent over half of the state’s K-12 demographic.

One of the best-attended sessions addressed the difficulties that school districts are facing amid accusations that their teachers are advancing a pernicious form of teaching that blames Anglos for racial inequality and singles out Anglo children for something akin to the racial sins of their fathers. According to the presenters, conspiracy theorists as well as the publicity surrounding Senate Bill 3 have reportedly influenced parents and other members of the community to disrupt school board meetings with unfounded accusations of teaching Critical Race Theory. Teachers, administrators and staff have also reportedly received death threats.

The session, titled “CRT Defined,” included representatives of the Fort Worth, Crowley, and Ysleta school districts. They described their difficulties, explained their origins, and offered a novel way for school officials to respond. Adhering to the debating principle that whomever controls the rules of engagement wins the dispute, they proposed that the discourse over race (e.g., Critical Race Theory) should incorporate the notion of equity in the entire school environment, including the notion of equitable learning opportunities for all students, not just Anglos. Specifically, they turned the issue of discriminating against white children in the curriculum on its head and maintained that this, too, is an equity issue about which all should be concerned. Attending sessions like these illuminate the kind of wisdom and knowledge that comes from our leadership, underscoring the importance of organizations like MASBA to create spaces where grassroots struggles may acquire strength and visibility while reinforcing values and motivating civic action.

The conference participants heard four major keynote addresses. The talented David “Olmeca” Barragán, a Hip-Hop performer and Instructor with the Interdisciplinary Gender and Ethnic Studies Department at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, gave the opening keynote talk titled, “Browning of America.” His uplifting message called on Latino people to assume confidence and pride in themselves and in a bright future that awaits us. We should be able to speak openly and with the knowledge that we have much to offer the world. His self-affirming statement in the poetic form of Spoken Word invoked and modelled the confident voice with which we should always speak.

The second keynote presentation was delivered by Dr. José Angel Gutiérrez, a founder of the Mexican American Youth Organization and the Raza Unida Party and Professor Emeritus from the University of Texas at Arlington. In the first part of his talk, he examined Mexican American history with the use of key publications. His message was that we have a vast historical and literary tradition and that we should strive to become sufficiently literate to advance our social movement for dignity and equal rights. Dr. Gutiérrez followed by exhorting us to action, frequently asking what are you going to do in light of continuing problems that Mexican Americans are facing. He pointed to the dismal education gap that the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board promised to fill but failed. They have now devised a new plan that will most probably also fail. We cannot depend on conventional institutions to solve our problems, he suggested, we need to take action on our own behalves.

Dr. Angela Valenzuela, Professor in the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy at the University of Texas at Austin titled her keynote address “Unmasking the Attack on Critical Race Theory as an Agenda to Deprive Our Access to the Inconvenient Truths of History.” Her principal argument was that the opposition to Ethnic Studies, Mexican American Studies in particular, does not have the moral or the philosophical wherewithal to deny us our historical destiny as an emancipated people. They depend on false conspiratorial arguments and outright misinterpretations of classroom learning to argue that we cannot be trusted to teach the youth, that we use race as a weapon to promote disdain against Anglos and blame their children for racial inequality. Fortunately, she expressed, we have both the First and the Fourteenth amendments to the Constitution and have learned from history the values of mutual respect, understanding and fairness towards all people. Through song and speech, her lyrical narration braided several strands of the political, intellectual, and spiritual in the context of a solemn Saturday-morning acknowledgement of lives lost on the morning of September 11, 2001.

April Hernández Castillo, an actress, writer and motivational speaker, shared the difficult experiences she encountered her life in a talk entitled “Your Voice, Your Choice.” She persevered despite self-destructive influences, an abusive relationship and thoughts of suicide, as if to say that we can and must persevere in life and that we must discover from within ourselves the resilient and self-protective spirit that can help us do this. Her life of near-tragic proportions invoked the idea that minoritized groups like us also face difficulties but we too can discover the resilient force within ourselves. Hernández Castillo was believable with her lovely persona of confident grace and honesty.

MASBA’s advocacy declaration, which appears prominently in conference materials as its self-defining statement, may be the most appropriate way to close as it best reflects the organization’s compassion and care for the education and general well-being of youth, especially Mexican American students:

Closing the Gaps

MASBA advocates for programs and practices that more quickly close the achievement gap for all Texas students, especially for the Hispanic students and English Language learners in our Texas public schools.

MASBA stands against all programs and practices that perpetuate and/or widen gaps in student performance.

Ensuring High-Quality Curriculum

MASBA advocates for high-quality curriculum for Texas public school students, particularly with respect to issues of equity, diversity and inclusion. MASBA supports ethnic studies for all students and high quality dual-language programs that promote bilingualism and biliteracy

MASBA stands against all curricula that do not reflect equity, diversity and inclusion, or that negatively portray the history or contributions of the diverse cultures represented by our students.

Solidarity

MASBA stands in solidarity with the students of our Texas public schools—particularly with our Hispanic students and English Language Learners—with their families, and with all persons who support them in achieving their dreams.

MASBA advocates for comprehensive immigration reform, for equitable treatment of all students irrespective of their immigration status and for all students who were brought to the United States as children and who have been educated in our public schools.

MASBA stands against racial profiling, discrimination based on immigration status, and all attempts to unfairly target persons based on race or appearance, and against all actions that instill fear and create instability in the lives of our students.

Diversity and Inclusion

MASBA advocates for racial justice and for policies and practices that help to ensure that the faculty, staff members, administrators and trustees of our public schools reflect the diversity and demographics of the students in our public schools.

MASBA stands against all attempts to inhibit equity, diversity or inclusion, and against all attempts that hinder a person from realizing his/her highest potential

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.