From the editors: In 2021, Not Even Past launched a new collaboration with LLILAS Benson. Journey into the Archive: History from the Benson Latin American Collection celebrates the Benson’s centennial and highlights the center’s world-class holdings.

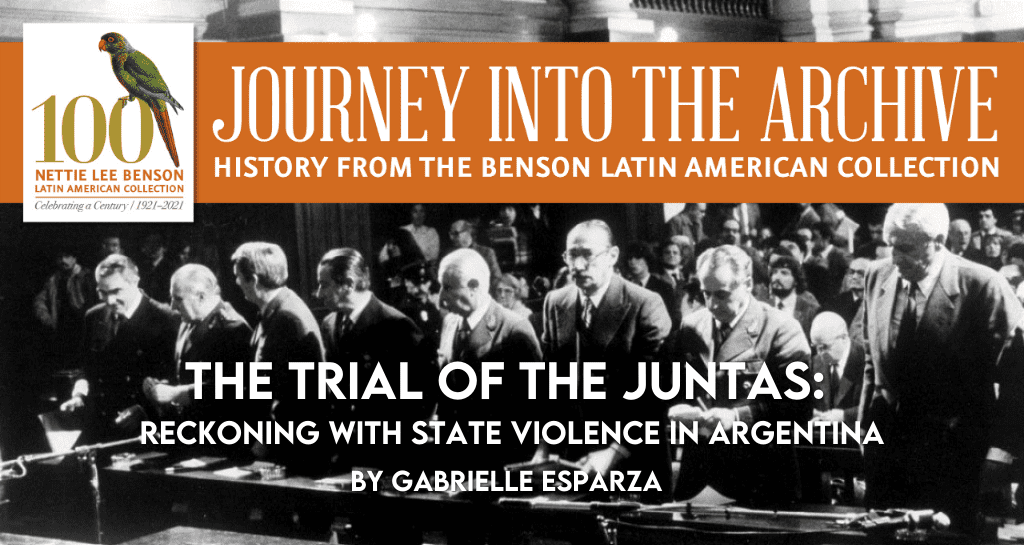

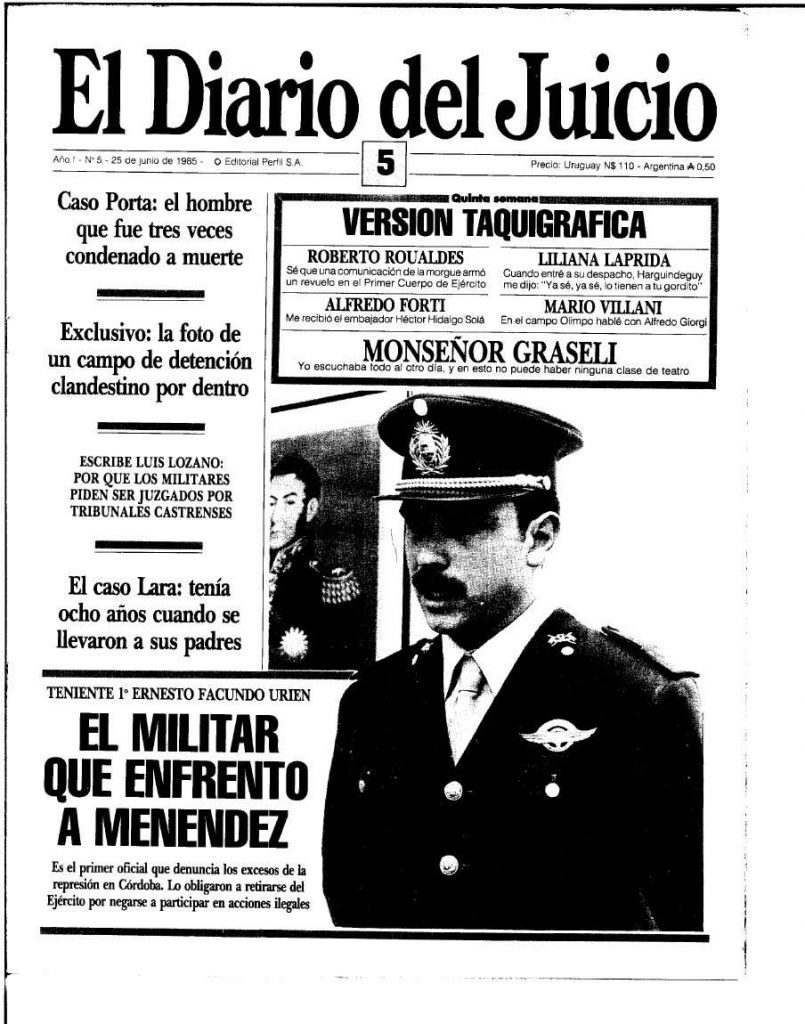

In April 1985, the historic trial of the military juntas that had ruled Argentina from 1976 to 1982 began in Buenos Aires. Nine members of three previous military juntas faced charges ranging from the falsification of public documents to homicide. Over the following eight months, the trial of the juntas captured national attention. Although not televised or aired by radio, the trial was open to the public and received detailed coverage in El Diario del Juicio, a weekly publication that documented the proceedings and included witness transcripts. The accessibility and publication of the facts surrounding the prosecution helped convert the trial into a national event, which served not only to punish the guilty but also to help create a shared understanding of the past.

At the Benson Latin American Collection, case transcripts of testimonies given by 828 witnesses at the 1985 trial occupy 10 boxes and more than 7,000 pages. The Actas Mecanografiadas document gross human rights violations and present damning evidence against senior military commanders, including former heads-of-state. Some feared that political or social changes would place the trial transcripts in jeopardy. As a safeguard against destruction and to ensure long-term preservation of these records, Argentine officials made efforts to deliver copies of trial transcripts and recordings to foreign archives.

Witnesses recounted dramatic details of torture and abuse, and their testimony served as Federal Prosecutor Julio Strassera’s most powerful tool during the trial of the juntas. Hundreds of similar accounts helped the prosecution establish a pattern of repressive state-sponsored violence. After leaving power in 1983, the armed forces had maintained that any unjust or innocent deaths were the result of errors or excesses committed by individual officers. Strassera’s case selection sought to disprove this defense by demonstrating that a sustained pattern of abduction, torture, and murder occurred countrywide. Documenting similarities across numerous military commands, Strassera argued that former leaders had established an apparatus of state terror and could not attribute the violence to a few renegade officers.

Witness testimony helped establish the facts of the 709 cases and detailed a systematic pattern of repressive practices, but the prosecution needed to prove a legal basis for punishment of the ex-leaders. Members of the three juntas did not directly engage in or supervise the described atrocities. However, they had issued the instructions calling for the annihilation of subversion. In the context of state-sanctioned violence, Strassera reasoned that the ex-leaders were indirect authors of the crimes committed because they exercised complete control of the repressive apparatus and over their direct agents or subordinates who engaged in the actual violence.[1]

The prosecution sought to demonstrate that the generals held responsibility for the actions of their subordinates due to the structure and culture of the armed forces. Within the military, the top brass could remove and replace anyone for noncompliance. Thus, the individual was interchangeable, and the crime would likely occur with or without that person’s participation. Furthermore, the armed forces encouraged total confidence in one’s superiors. Retired Navy Officer Adolfo Scilingo, who would gain fame in the 1990s as the first man to break the military’s pact of silence, explained, “In the navy, there’s no such thing as orders that aren’t legal.”[2] Scilingo’s account detailed a military institution that expected blind obedience and discouraged individual assessment of an order’s legitimacy.

The testimony of military officers during the trial helped the prosecution establish the unique context in which human rights violations occurred. First Lieutenant Ernesto Facundo Urien detailed how the hierarchical structure of the armed forces encouraged compliance because those who expressed differing opinions risked their career.[3] During his testimony, Urien recalled various incidents that led him to doubt the military’s methods in the so-called “war on subversion.” Superiors had ordered Urien to dress as a civilian, with his military arms, and patrol public spaces. He also provided security during transfers of personnel and prisoners to La Perla military installation, which served as a clandestine detention center during the dictatorship. At La Perla, Urien witnessed a detainee, “hooded, hands and feet bound.”[4] Urien questioned these tactics, but superiors defended their actions within the context of a civil war. Ultimately, Urien was forced into retirement in 1980 for “not sharing the philosophies that the institution upheld.”[5]

Fear of repercussions for speaking out extended beyond professional concerns. “The climate that existed was don’t risk frank opinions,” testified Captain Félix Roberto Bussico, “There inside, life had no value . . . regardless of the life involved.”[6] An officer could refuse to comply with orders, but the repressive apparatus bred fear of retaliation and limited subordinates’ decision-making capacity. Bussico’s testimony and those of other military officers demonstrated that a minority of lower-ranking officers did not devise the violent tactics of the preceding years. Instead, orders for torture and disappearance derived from the highest ranks and bred a culture of indiscriminate violence.

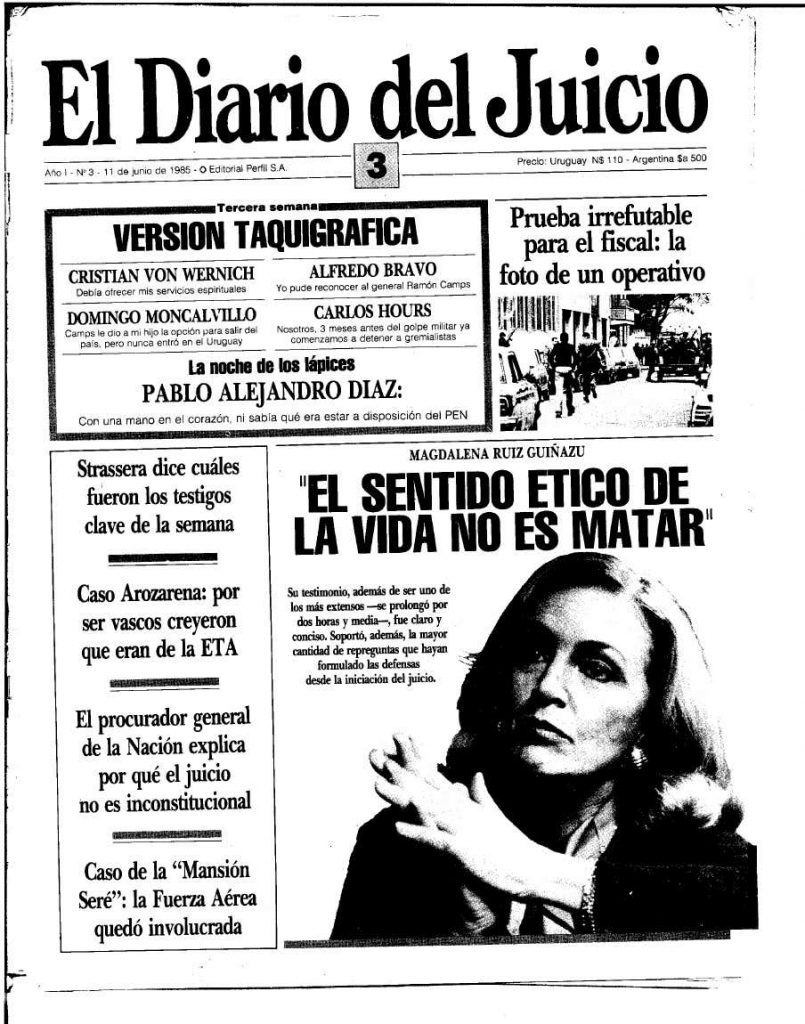

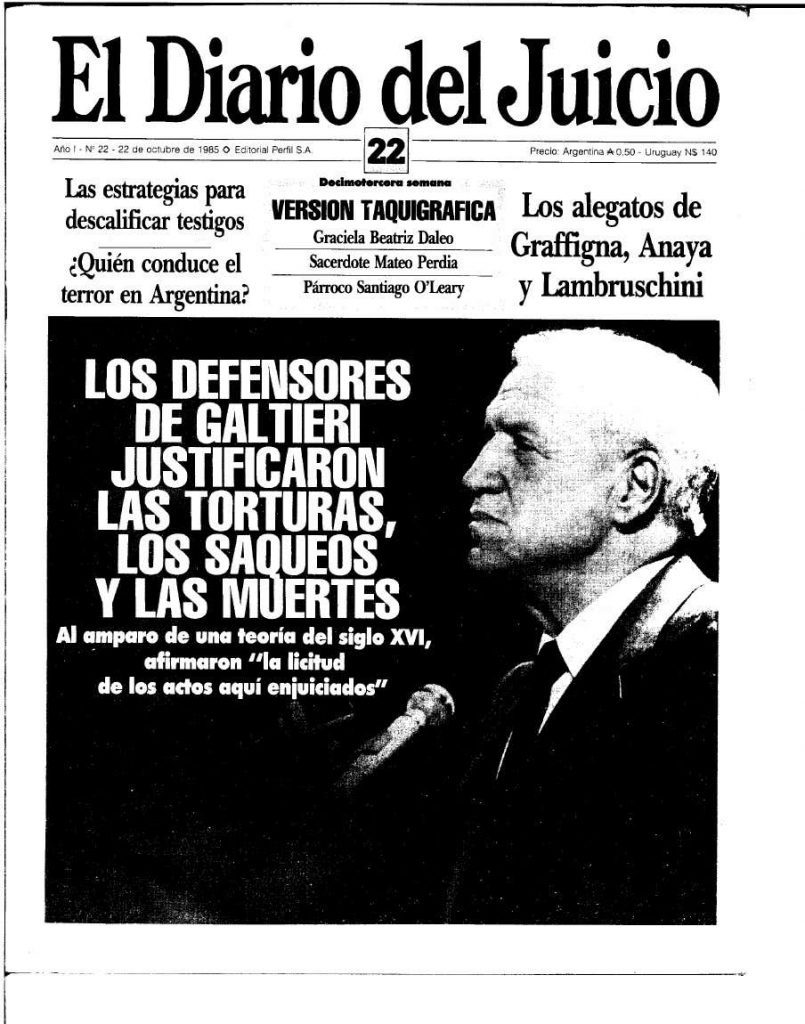

As evidence mounted against the military leaders on trial, the defense sought to justify the armed forces’ violent methods in the context of a brutal civil war. The accused believed that the trial punished them for acts of service to the nation. “He who saves the nation does not break any law,” asserted the defense counsel for Lami Dozo, air force general and member of the third junta.[7] The defendants understood their actions within the context of an ideological war, so they believed defeating subversion justified their methods and absolved them of criminal responsibility. Following this reasoning, the defense frequently resorted to attacks on the witness’s or alleged victim’s character. This strategy often backfired. After an aggressive line of questioning, Magdalena Ruiz Guiñazú, a journalist and member of the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons, replied with her own question. “Is it lawful,” she asked, “to torture, kill, and make people disappear?”[8] Guiñazú’s retort highlighted the criminality of the defendants’ actions regardless of the victims’ alleged political affiliations or actions.

Issuing its final verdict in December 1985, the Federal Court of Appeals rejected the defense’s arguments. The chamber responded that the defendants’ actions were abusive. “There was no intensification of originally adequate means but rather illicit instruments,” explained the judges.[9] They held that “combat should never escape the framework of the law.”[10] The sentencing further clarified that the military juntas had access to legal measures to combat so-called subversives. According to the members of the Federal Court of Appeals, the dictatorship could have declared emergency zones, dictated public warnings, made summary judgements, and even applied death sentences.[11] The former leaders had not employed these methods.

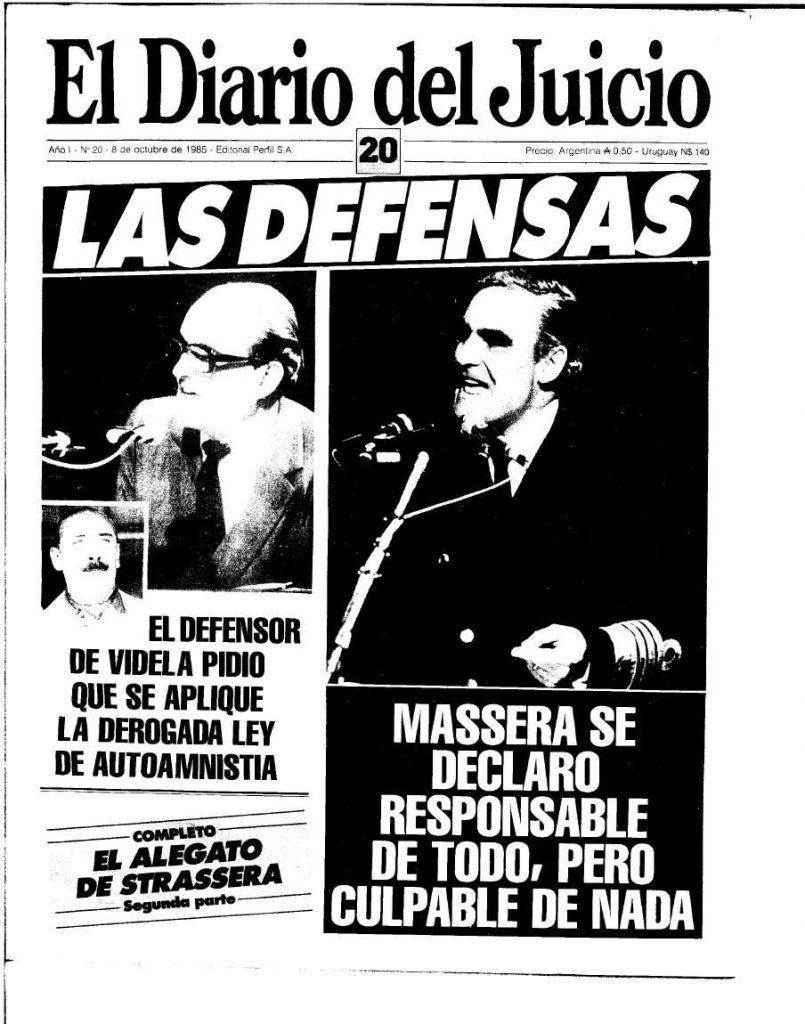

In its entirety, the judgement filled 868 pages. The judges sentenced General Jorge Videla and Admiral Eduardo Massera to life in prison; General Roberto Viola to seventeen years in prison; Admiral Armando Lambrushini to eight years in prison; and Brigadier General Osvaldo Agosti to four and one-half years in prison. The sentencing also stripped them of their military status. Those acquitted were the second junta’s Brigadier General Omar Graffigna, and the three leaders of the third junta, General Leopoldo Galtieri, Admiral Jorge Anaya, and Brigadier General Lami Dozo.[12] Members of the second and third juntas generally received lower sentences because more than eighty percent of the kidnappings occurred during the first two years of the dictatorship.[13]

The verdict generated conflicting reactions from the public. Particularly for those who had suffered personally, the sentencing seemed far too lenient. Emilio Mignone, who became a prominent human rights activist after his daughter disappeared in 1976, maintained that “the sentencing [did] not satisfy the expectations of a democratic society.”[14] Others claimed the trial was nothing more than a political show. However, the trial had respected legal codes and due process. Strict adherence to the law during the trial of the military generals showed the power of democratic processes to condemn illegal acts, even when done by former leaders. This was an important act in a country prone to military intervention and the first step in establishing greater civilian control over the armed forces.

The trial and resulting records document gross violations of human rights. Official estimates place the number of disappeared between 10,000 and 30,000, among them more than 500 babies and children. Witness testimony and evidence helped prove that these disappearances occurred as part of an apparatus of state-sanctioned terror. More importantly, the testimony also demonstrated that the military commanders had orchestrated the violence and deserved punishment. This was clear even to those sectors of Argentine society that had supported the dictatorship. The trial, which occurred within the framework of democratic laws and institutions, publicly and officially condemned the military dictatorship.

Today, the transcripts housed in the Benson Latin American Collection serve as an archive of Argentina’s early efforts to reckon with its legacy of state-sponsored violence. More than thirty years later, such efforts continue in the form of new and ongoing trials for human rights abuses committed during the dictatorship. The trials, and the crimes they describe, are shocking. But, as disturbing as the details are, we are fortunate to have access to such a collection. The Actas Mecanografiadas bear witness to a difficult history and reveal Argentine society’s judgment of its recent past.

[1] Carlos Santiago Nino, Radical Evil on Trial, (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996), 85.

[2] Horacio Verbitsky, Confessions of an Argentine Dirty Warrior: A Firsthand Account of Atrocity, (New York: The New Press, 2005), 27.

[3] Ernesto Facundo Urien, Box 6, Actas Mecanografiadas, Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas Libraries, the University of Texas at Austin.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] “No creí que en la Armada pasara eso,” El Diario del Juicio, July 23, 1985.

[7] Nino, Radical Evil on Trial, 86.

[8] Magdalena Ruiz Guiñazú, Box 4, Folder 53, Actas Mecanografiadas, Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas Libraries, the University of Texas at Austin.

[9] “Introducción al dispositivo,” El diario del Juicio, January 28, 1986.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Secretaria de Derechos Humanos de Argentina. Comisión Nacional sobre la Desaparición de Personas, Nunca más: informe de la Comisión Nacional sobre la Desaparición de Personas (Buenos Aires: Eudeba, 2009), 302.

[14] “Habla Emilio Fermin Mignone, Titular del CELS,” El Diario del Juicio, January 14, 1986.