Both detailed environmental and medical histories of the Antebellum South are rare. Works that combine the two even more so. In The Health of the Country: How American Settlers Understood Themselves and Their Land, Conevery Bolton Valencius does just that. She argues that 19th-century American settlers saw an important relationship between the “health” of the landscape they were settling and that of their own bodies. She asserts that most histories of Western expansion have overlooked this dimension of the Antebellum settler mentality, and in doing so have not accurately represented the thoughts and practices of the time.

White settlers in the Antebellum South saw the human body and the natural environment as connected, having similar “balances,” and undergoing similar processes. Naturally, this changed the way settlers viewed and used the land. They anthropomorphized landscapes, ascribing levels of “health” to the land, airs, and waters of their environments. Much of the Antebellum settlers’ logic about the health of landscapes mirrored the logic of their medical studies and practices. Stagnant water and air were seen as inherently sickly, just as blockages or a perceived lack of flow of fluid in the body was. Understanding this association between the way Antebellum settlers perceived human biology on the one hand and environmental landscapes and processes on the other provides valuable insight into patterns of medicinal practice, land use, and natural resource extraction during the period of American westward expansion.

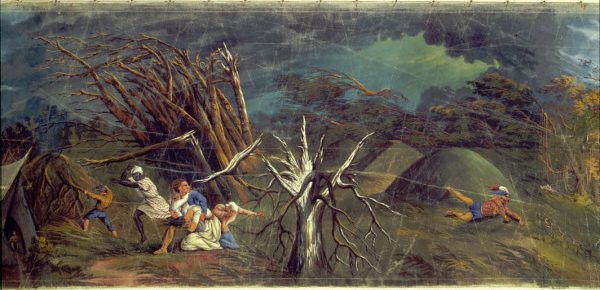

Valencius’ thoughtfully constructed narrative highlights the extent to which white settlers and the enslaved Black populations they forcibly transported were vulnerable to environmental factors when migrating west in the Antebellum period. She describes in detail the difficulties settlers encountered during the initial period of “seasoning” or acclimation to the “foreign” new landscapes, climates, and illnesses of the Mississippi Valley and the western U. S. While they were armed with preventative measures and remedies for diseases, settlers commonly understood that their lives were ultimately at the mercy of the natural world. Additionally, settlers believed the process of clearing and cultivating land exposed them to the miasmas supposedly contained within natural environments. Migrants did not exercise full control over preventing and healing disease or altering the landscape, making colonization of new environments especially daunting.

In writing this history, Valencius diverges from the triumphant progress narratives often associated with the history of American westward expansion. She does not do so to downplay the centuries of horrific violence committed by European settlers against Black and Indigenous populations. Rather, this history is meant to disrupt the idea that white settlers were all-powerful and to represent their thoughts and fears of migrating west with more accuracy and nuance. Part of the explanation for the distinctiveness of Valencius’ Western expansion narrative lies in its unusual and diverse primary sources. Valencia does not rely solely on reports from white men in positions of power, such as political or military figures, who often had a vested interest in promoting “triumphant” frontier narratives. Instead, she analyzes the personal writings of white settlers through letters, diaries, and stories. She also makes use of medical exam documents produced by practitioners of “medical geography” and “Southern medicine,” many of whom were not formally educated doctors. Additionally, by incorporating the stories of enslaved people like Solomon Northup, as well as carefully engaging with the interviews of formerly enslaved people, Valencius highlights how Black populations conceptualized and experienced human and environmental health differently than their white oppressors.

Valencius also outlines the connections between nineteenth-century American medical geography and the formal political process of settling, using, and acquiring land. She argues that coming to know a place by observing weather patterns, classifying natural resources, and charting areas with higher risk of illness contributed to the physical process of western expansion and settlement. These documents provided vital information about new territories that assisted military and economic operations and influenced the migrations of other white settlers. After all, as Valencius notes, “ambitious families moved to healthy places, not sickly ones” (6). Additionally, she describes how at times the “health” of landscapes was not only related to the perceived risks of illness but was closer to a description of the discomfort settlers felt in such an unfamiliar landscape. In labeling environments as unhealthy, or even “wild” or “savage,” settlers expressed an innate desire to “improve upon” new territory. “Improving” or “taming” the landscape, Valencius shows, contributed to a connection between farming and virtue, and almost always involved some form of environmental destruction.

The Health of the Country reveals that the medical and environmental histories of the Antebellum South are inseparable. Moreover, it provides important context to the political and cultural history of the same period. Valencius urges readers to look beyond present-day distinctions between physical health, environmental conditions, and nation-building imperatives in order to better understand the language and experiences of migrants in the expanding American west. Her book pushes us to understand Antebellum medical and environmental histories as not only interconnected with each other, but also as deeply linked to the politics of colonialism and expansion.

Francis Russell is a doctoral student in the Department of Geography and the Environment at the University of Texas at Austin. They study the social and environmental resilience and vulnerability of coffee farmers in Puerto Rico. In their work, Francis uses both quantitative geospatial and qualitative ethnographic analyses.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.