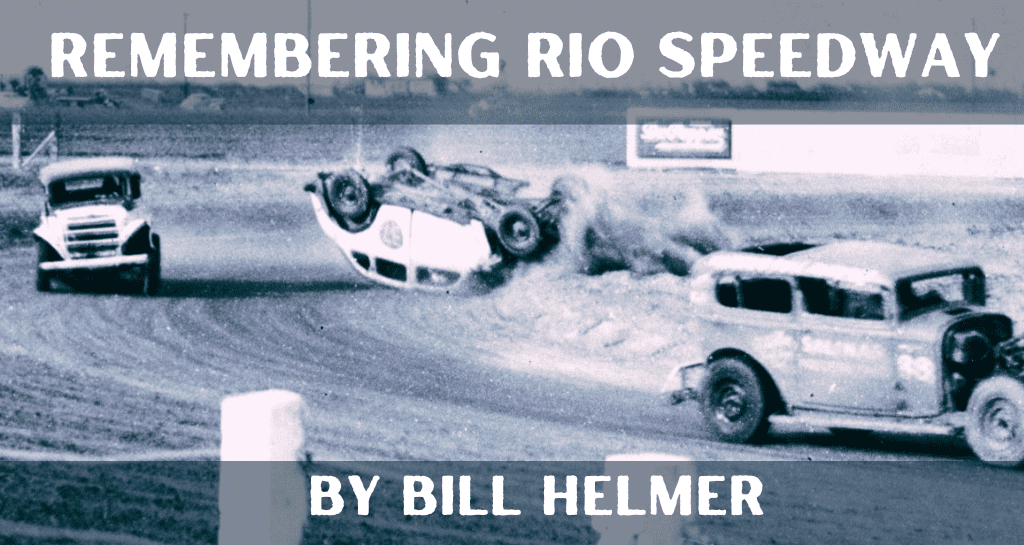

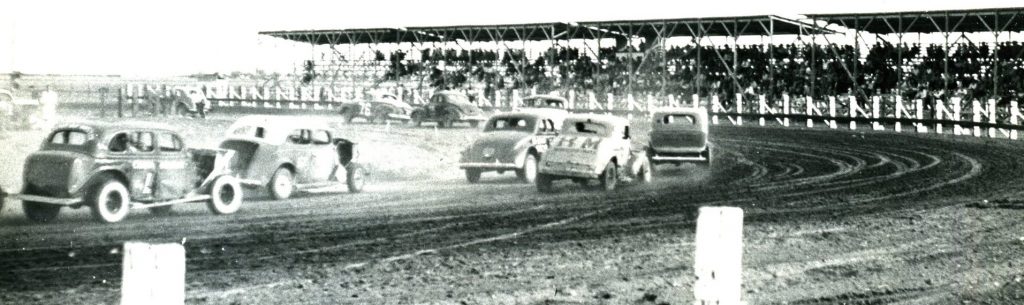

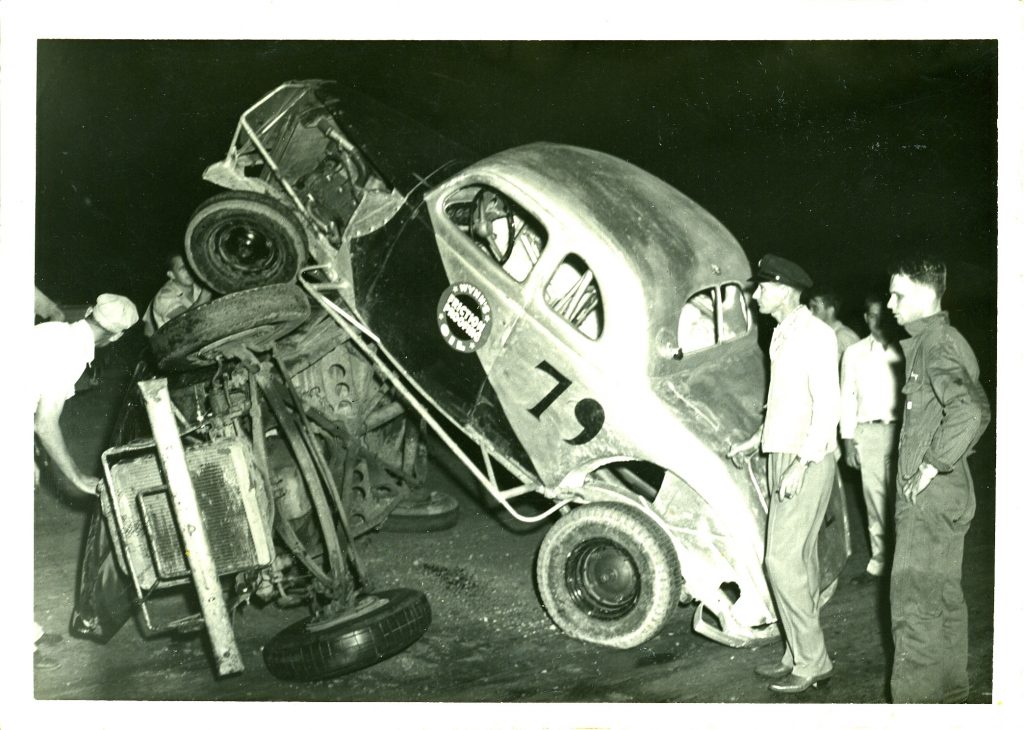

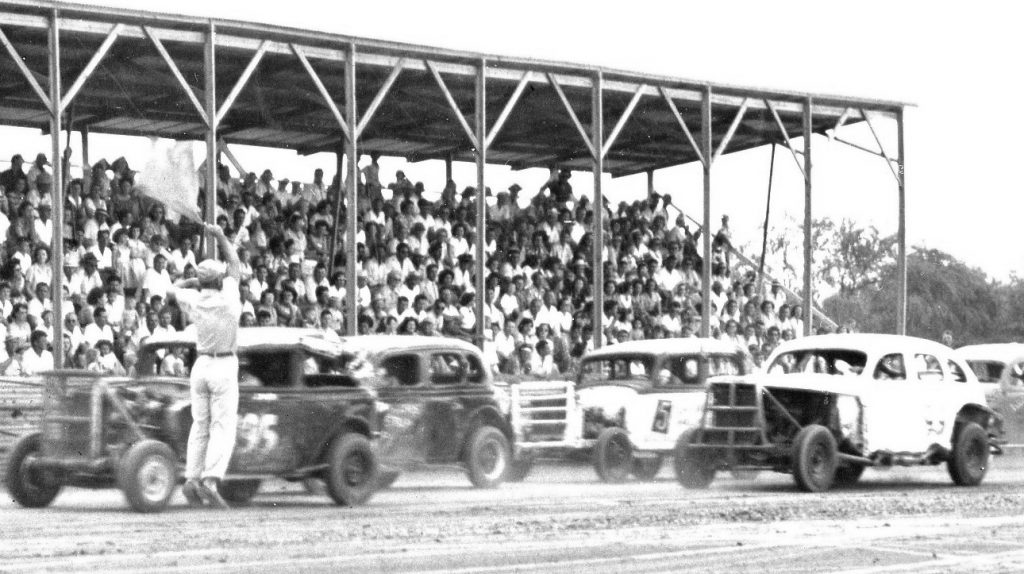

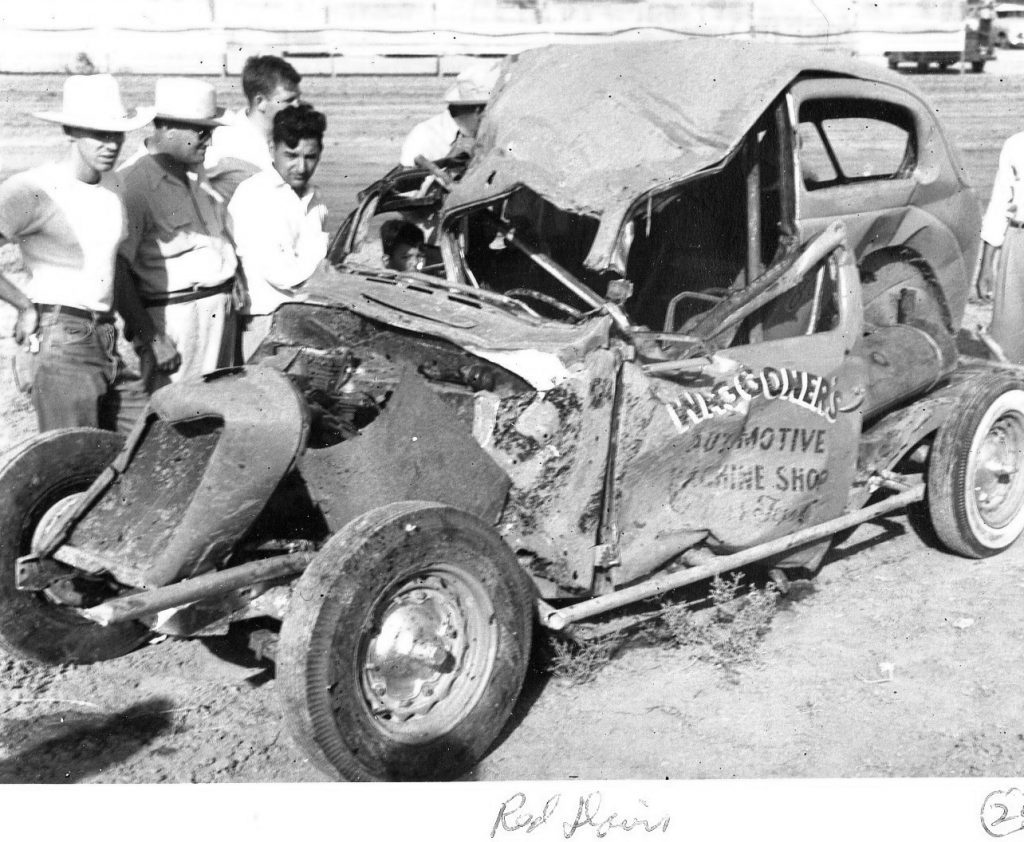

“THRILLS! SPILLS! CHILLS!” was how Rio Speedway advertised its stockcar races, and at that little track we must have totaled classics worth a million dollars. Maybe I’m exaggerating, but you get the idea.

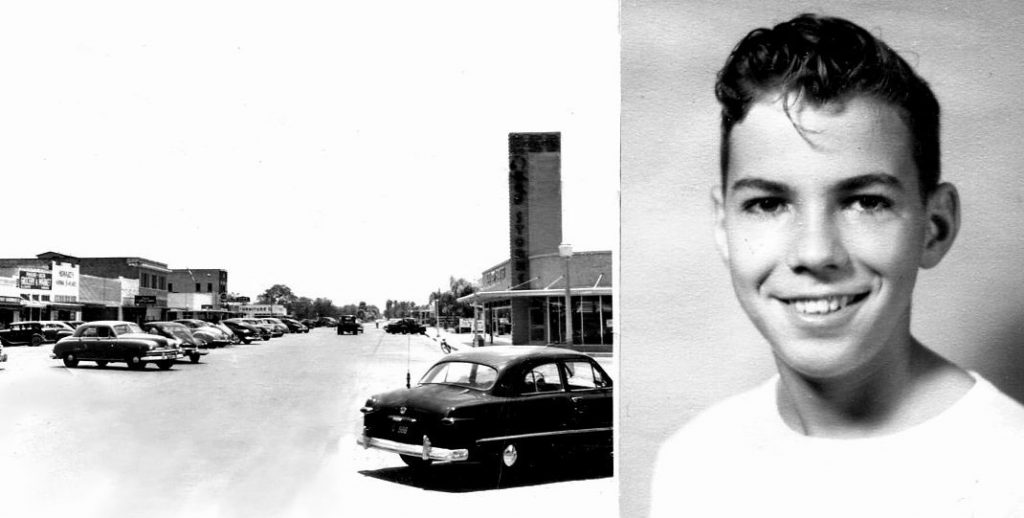

When I lived there, Pharr, Texas, was a hamlet of 5000, two hundred miles south of San Antonio and just across the river from Reynosa, Mexico. It shared (and I suppose still does) the city limits sign with neighboring McAllen. Both towns are at the western edge of the Rio Grande Valley’s citrus belt. (I don’t know why they call it a valley, because the land is flat as a pancake.)

Those soon blended into stocks—Fords from the 1930s, with a few Plymouths, Chevies, and a Buick or two. All were built in the Thirties, had survived World War II, and were passing their final days up on blocks or in junk yards, where you could pick one up for $20 or $30.

Rio Speedway opened in 1946. It was five miles south of town on the road to Reynosa and at first it featured home-brew “midgets,” little home made open-wheel machines built strictly for auto racing. These were small in size and usually powered by little Ford ’60’ motors designed in the early 30s.

Once you got your car running and tuned it up, you stripped it of upholstery, installed a surplus airplane seat, and sometimes added what passed for roll-bars. You also cut off the fenders and installed large plumbing pipes to protect the radiator. Such refinements made it a “modified” stock, and if the car was especially fast and you were especially good, you might win $50 for first place in the fifty-lap “feature.” First place in a ten-lap “heat” would earn you maybe $15. Short of that it might be $5 and some cartons of cigarettes.

I was just a kid, but I had a Kodak with shutter speeds and it let me talk my way past the one-dollar ticket booth. Now I’m thinking this happened because my dad owned the Hub Cafe, a truck stop, the only place in town where you could get a beer.

I came to know the owner of the racetrack and quite a few drivers. The owner was Wayne Hartnett, I guess nearly fifty, and he lived in a fine brick house just outside of town. He also had a really fine daughter, Darlene, about my age. But she had class and I didn’t, so I lacked the courage to ask her for a date. (For that matter, I didn’t know how to date.)

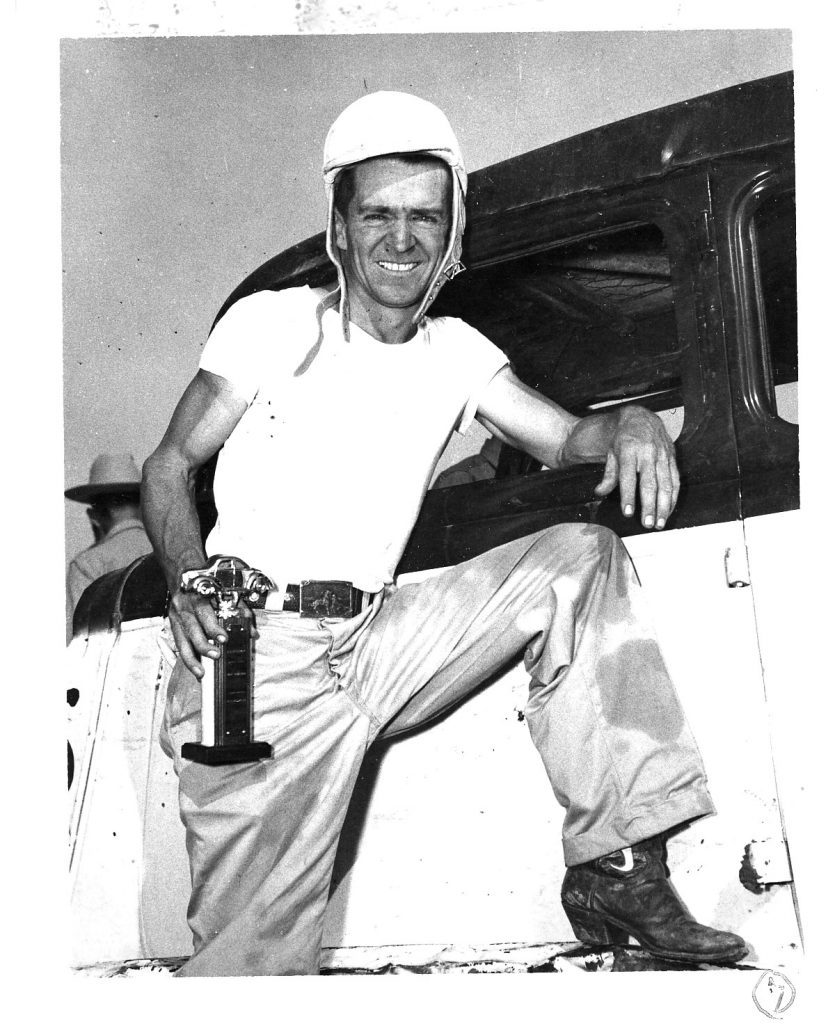

Most of the drivers were regulars, and most had raced the open-wheeled midgets before moving into stocks. They would buy the 4×5-inch photographic prints I made at home and carried with me in a shoulder bag. Twenty-five cents each.

Of all the drivers, my favorite was Roy Cameron. He was a frequent winner and so friendly that everybody liked him. His main rivals were Red Davis, Bob Whistler, and J. W. Brown. Red was fun and sometimes let me ride with him on warm-ups, if I held tight to the roll-bars and there weren’t other cars on the track. Bob Whistler was OK; I was told he had a plate in his head from a car wreck some years earlier. J. W. Brown was a little stand-offish but had a really exotic car. It was a stripped-down ‘32 Ford with big roll-bars front to back and over, and I’m surprised they even let him race (although “they” was Mr. Hartnett).

Next to Roy Cameron, my other favorite driver was Slim Nagy. He was tall, decent looking, didn’t win all that often, and specialized in bad luck. As a crop-duster (his day job) he once piled up his Stearman biplane, an Air Corps trainer left over from the Thirties. He was skimming a cotton field, wheels touching the plants, when he was surprised by tree stump that wasn’t supposed to be there. The plane flipped upside down and shook him up, but all he had to do was pop his seat-belt.

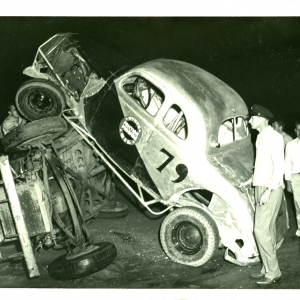

Where he really had bad luck was at the track, first in a midget and then in stocks. When he crashed his midget, the radiator hose broke and scalded his legs. Later he rolled stocks, maybe three or four times. Like nearly all the cars, his had an aluminum seat surplussed from the jillions of T-6 trainers used in World War II, and his wasn’t anchored too well. The roll cost him a broken collar bone. I don’t know how long it takes for collar bones to heal, but he was back to racing a month or so later.

Incidentally, Mr. Nagy gave me my first airplane ride. He said Would I like to? and I said Sure! In those days, nobody worried about parental permission or things like liability insurance.

Getting back to stock cars—

If Slim’s luck was sometimes bad, the two best dumb-luck guys were the Byrd Brothers, Dave and Elmer. For them, racing was a labor of love, if not much else. They never missed a Sunday, never rolled their cars, and often finished last. They both lived in a small frame house and were so friendly that I liked to hang out there, watch them tinker with their cars. I don’t know what Dave did, but Elmer was the projectionist at our little Texas Theater. I’d visit him in its upstairs projection booth and he’d show me things like how movie film would flare up if you touched it with a match. I don’t know when they changed its chemistry, but back then movie film was nitrate-based. He smoked, other projectionists smoked, and I’ve always wondered why more movie theaters didn’t blow sky-high.

Anyway, every race had its spins and crashes and rolls that were monitored by our firetruck and the funeral home ambulance. The firetruck was manned by three or four of our Volunteers, and two Angels of Mercy brought the ambulance. I think all of them came unbidden, because they liked to watch the races.

In 1954 I graduated high school and went off to college. Rio Speedway remained in operation, but not for very long. During vacations I attended several races but knew fewer and fewer drivers. The Valley’s biggest sport was high school football, ferociously played among the dozen or so towns that lined the Rio Grande. The other sport, if you could call it that, was auto racing.

I’m still in touch with friends who tell me that the Valley’s population is now several hundred thousand and the road past Rio Speedway is residential all the way to Mexico.

These days it hurts to watch those antique auto auctions on television and think of all the classic cars we wrecked.

Photographs: All images come from the author.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.