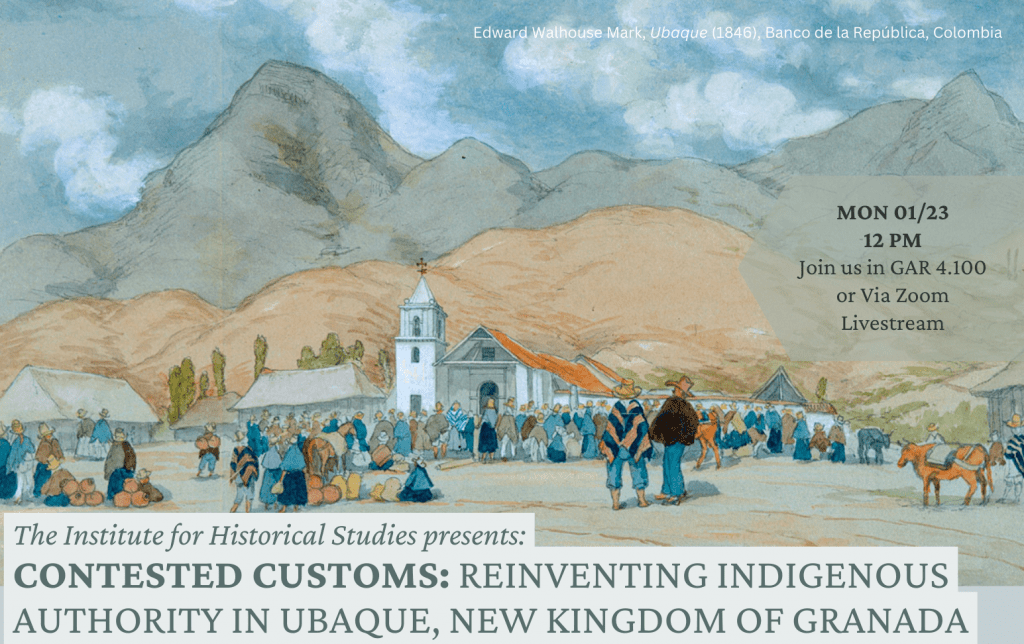

This paper explores the changing forms of Indigenous authority in Ubaque, a highland Andean valley of the New Kingdom of Granada (present-day Colombia), in the sixteenth century. According to Hispanic law, caciques were local nobilities who enjoyed a right to rule their communities keeping to their customs. As such, they were recognized as part of the imperial administrative organization; they were designated by the Crown to lead their communities, which would maintain their structure and goods for tribute. However, the imperial administration also expected to make Indigenous peoples into Catholic vassals of the monarchy, who lived pious lives. With this aim, clerics and civil authorities outlawed the practices, ceremonies, and symbolic languages that created bonds between caciques and their communities. This presented a challenge for caciques, who had to figure out how to play this dual, conflicted role maneuvering between Indigenous political cultures, Catholicism, and colonial demands. In this paper, I explore the ways in which two caciques of Ubaque grappled with this ambivalence, absorbing the contradictions of Hispanic colonialism. I argue that in sixteenth-century Ubaque, the Hispanic monarchy’s ambivalent approach to Indigenous customs and cultures led Indigenous authorities in a quandary over aligning with the traditions of their communities or the monarchy’s requirements. I place the emphasis in the structures of colonialism, rather than individual choices.

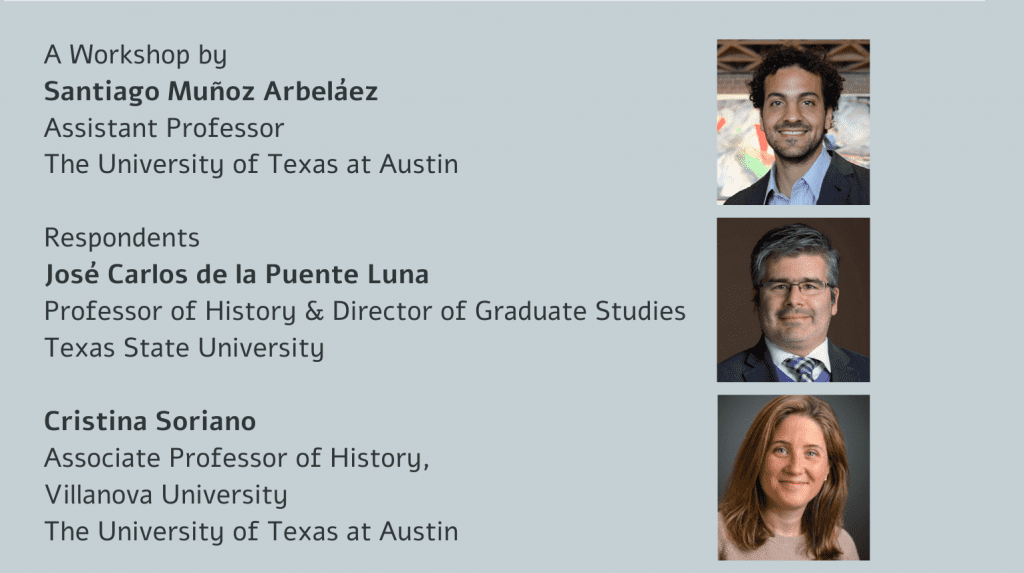

Dr. Santiago Muñoz Arbeláez (Ph.D., Latin American History, Yale University, 2018) is Assistant Professor of History at The University of Texas at Austin. His research and teaching focus on the interactions between Indigenous peoples and European empires in the early modern Atlantic world, combining material culture, agrarian history, and the history of books and maps. His book Costumbres en disputa. Los muiscas y el imperio español en Ubaque, siglo XVI (Bogotá: Ediciones Uniandes, 2015) reframed the history of the encomienda—one of the most contentious institutions of the Spanish empire—through an ethnographic look at everyday interactions between Muiscas and Europeans. His current book project, tentatively titled “Empire’s Fabric: The Making and Unmaking of New Granada,” examines the making of a centralized political entity (a “kingdom”) among the ethnically and geographically diverse landscapes of the northern Andes. He has published widely on the history of Colombia’s map, from the earliest Indigenous and European depictions of the New World to the early 20th Century. In 2015, he cofounded Neogranadina—a Colombian non-profit organization devoted to making digitization and digital tools available to local archives and community groups in Latin America. He also developed the bilingual digital history project Paisajes coloniales: redibujando los territorios andinos en el siglo XVII | Colonial Landscapes: Redrawing Andean Territories in the 17th Century, which explores the transformation of Indigenous homelands into colonial landscapes through the analysis of a 17th-century painting of the Bogota savannah. This project is part of a broader engagement with new pedagogical resources in Colombia and Latin America.

Respondents:

José Carlos de la Puente Luna

Professor of History & Director of Graduate Studies

Texas State University

Profile

Cristina Soriano

Associate Professor of History, Villanova University, and

(Future) Associate Professor of History, The University of Texas at Austin

Profile

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.