From the editors:

January 22nd, 2023 marked the passage of fifty years since the death of former president Lyndon Baines Johnson, a man whose remarkable but also controversial career in public life looms large both over the history of his home state of Texas and the United States as a whole. To better understand LBJ’s achievements and failures, Not Even Past reached out to Mark Atwood Lawrence, a distinguished historian who also serves as the Director of the Johnson Presidential Library. We were particularly interested in how scholars, political leaders, and members of the public understand LBJ’s legacy – and how their understandings have changed in the half-century since Johnson’s passing. The questions, along with Dr. Lawrence’s answers, appear below. They have been lightly edited.

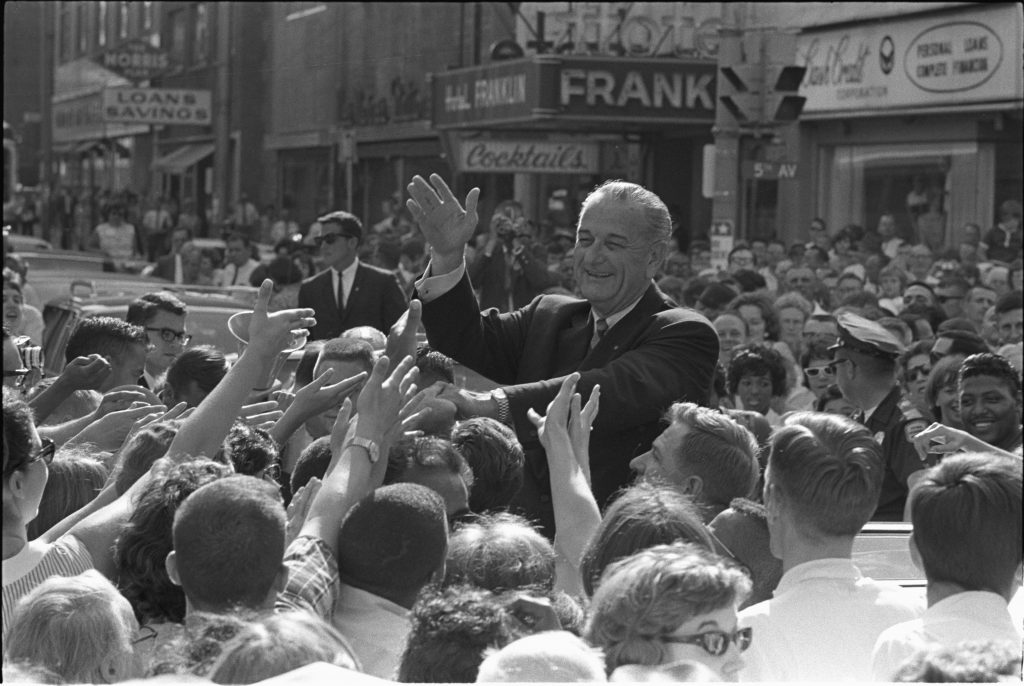

Not Even Past: Every year, hundreds of thousands of people visit your institutional home, the Johnson Presidential Library. We’ve both visited ourselves, and we’ve been struck by the fact that so many people seem to respond viscerally and emotionally to LBJ’s towering historical presence—we’ve seen people crying, for example, and not just in connection with the Kennedy assassination. As the Library’s director, what impression have you formed of the ways in which people remember and respond to LBJ today?

Mark Atwood Lawrence: There’s no question that many visitors to the LBJ Library have strong reactions to the story that we have to tell. This emotional response results, I think, from the fact that the Johnson administration made profound impressions for multiple reasons. Some Americans no doubt respond most powerfully to the story of the Vietnam War, the ugliest mark on LBJ’s record as president. Although Johnson inherited the Indochina problem from earlier presidents, he rightly stands out as the president who made the pivotal decisions to send hundreds of thousands of military personnel to wage a war that would ultimately kill more than 58,000 Americans and at least two million Vietnamese. Controversies around America’s most divisive war have cooled a little over the years, but passions still run high.

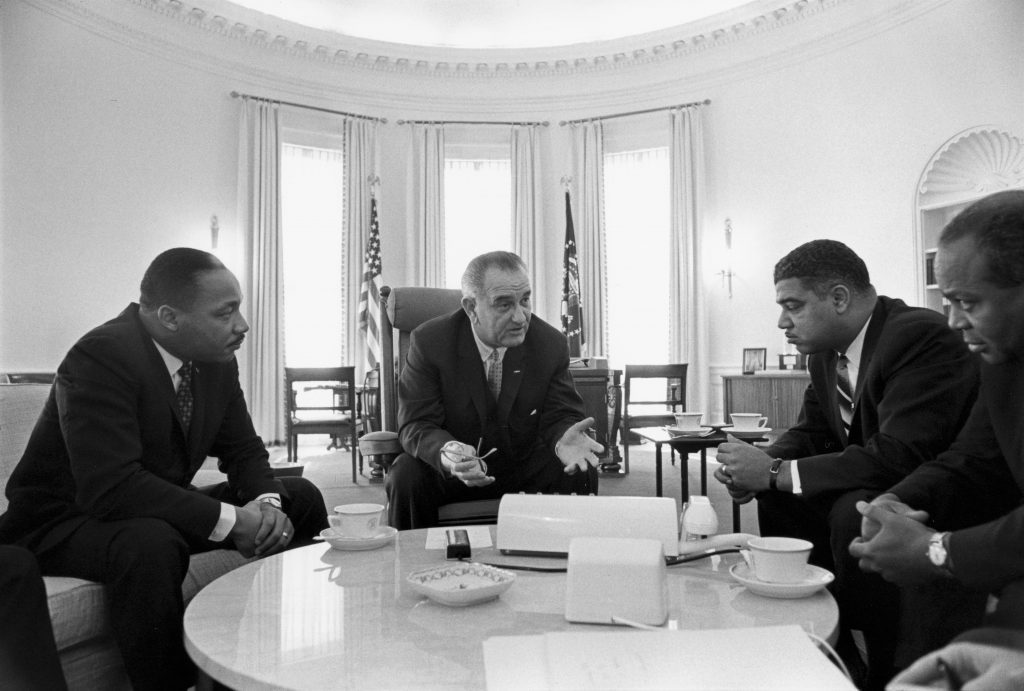

Many people also respond powerfully to the aspect of the Johnson presidency that shines as LBJ’s greatest achievement: the civil rights laws that ended Jim Crow and laid the groundwork for a new era of American history. Above all, Americans respond to the story of LBJ’s support for the civil rights struggle in Selma, Alabama, that culminated in the “Bloody Sunday” confrontation on the Edmund Pettus Bridge and the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. President Johnson’s invocation of the movement’s rallying cry – “We shall overcome” – during his speech to a joint session of Congress still gives me the chills almost sixty years later, and I suspect many others have a similar reaction.

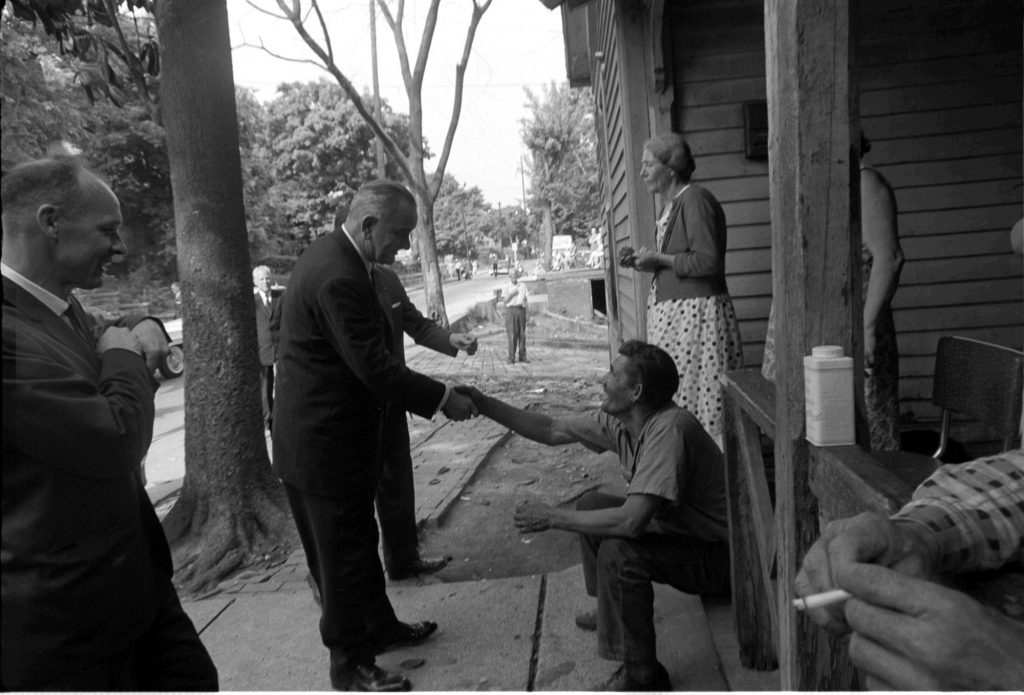

Some Americans also feel debts of gratitude to LBJ for elements of his Great Society reform agenda that brought life-changing advantages to many people now in their 60s and 70s. Head Start, Medicare, Medicaid, and various consumer protections, for example, helped lift many beneficiaries out of poverty and enjoy healthier and more secure lives. Lyndon Johnson doesn’t deserve all the credit for these breakthroughs, but he unquestionably applied his prodigious energy and political skills to creating new opportunities for people who had never before enjoyed such advantages. Underlying these accomplishments lay Johnson’s genuine sense of compassion, born of his own deprivation as a child in the Texas Hill Country, for those who lived, as he put it in 1965, “on the outskirts of hope.”

NEP: In a recent interview published by the Guardian, you suggested that Johnson has been the subject of a “reappraisal” over the course of the last decade and a half. Could you elaborate on that, and on how you think it has changed the way scholars like yourself understand LBJ?

MAL: When LBJ left office, and for many years thereafter, he was shrouded in disrepute. Years of urban unrest, a perception of rising crime rates, and widespread backlash against his civil rights bills certainly hurt him in the eyes of many Americans. These critics saw the Great Society not as a welcome blow for opportunity and social justice but as an expensive intrusion of federal power into the lives of ordinary hardworking citizens. There is no doubt, though, that the Vietnam War did most to damage LBJ’s reputation in the years after he left the White House. Critics on the right lambasted him for failing to do what was necessary to win the war, while critics to his left scorned LBJ as the architect of and ill-conceived and ignoble intervention in another country’s civil war. Virtually no one, in other words, saw much to like in LBJ.

Much has changed over the last couple of decades, and polls of presidential scholars now typically rank Lyndon Johnson among the top ten or 15 presidents of all time. Part of the reason is surely the simple passage of time, which had diminished the passions connected to the Vietnam War. To be sure, new scholarship about LBJ’s handling of the war has not been kind to him. New work has emphasized the ways in which political calculation and simplistic acceptance of Cold War assumptions drove President Johnson toward deeper embroilment in Vietnam. Still, fewer Americans are now invested in old controversies around U. S. decisions. In a roundabout way, too, LBJ’s reputation has probably improved as later presidents struggled with grinding wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. We can now see that LBJ was hardly unique in failing to appreciate the limits on American power. In any case, less vilification of Johnson in connection with the war has encouraged people to take another look at his enormous accomplishments in the domestic arena, particularly with respect to civil rights.

The weakening obsession with the Vietnam War has also encouraged academic authors to see a few striking accomplishments in LBJ’s handling of international affairs. Above all, we can now see more clearly than ever the ways in which the Johnson presidency laid the groundwork for the superpower negotiations that would come to fruition during the Nixon period, when U. S. and Soviet leaders reached a series of important agreements to reduce Cold War tensions. We can see as well that Johnson deserves credit for the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty that was signed in 1968, a crucial agreement that still shapes international life in the twenty-first century.

But perhaps the biggest reason for LBJ’s improved standing flows from the extreme polarization of American politics since the 1990s. The resulting dysfunction in our political system makes LBJ stand out more clearly than ever as a leader who was able to get things done. In sharp contrast to leaders today, he scored success after success by working across the partisan divide, assembling broad political coalitions behind ambitious goals, and embracing a spirit of pragmatic compromise. Americans seem to be wondering why these qualities have all but disappeared in today’s Washington and how to bring them back. LBJ thus stands out as a model to be emulated.

NEP: You made a similar point in your Guardian interview, wherein you noted that contemporary partisan polarization and institutional gridlock has created a “longing” for the kind of decisive systemic change LBJ was able to bring about. However, you also suggested that LBJ himself, talented negotiator and coalition-builder though he was, would likely be flummoxed by the kind of dysfunction that prevails today. This raises an interesting question: to what extent were Johnson’s successes products of his time rather than his leadership?

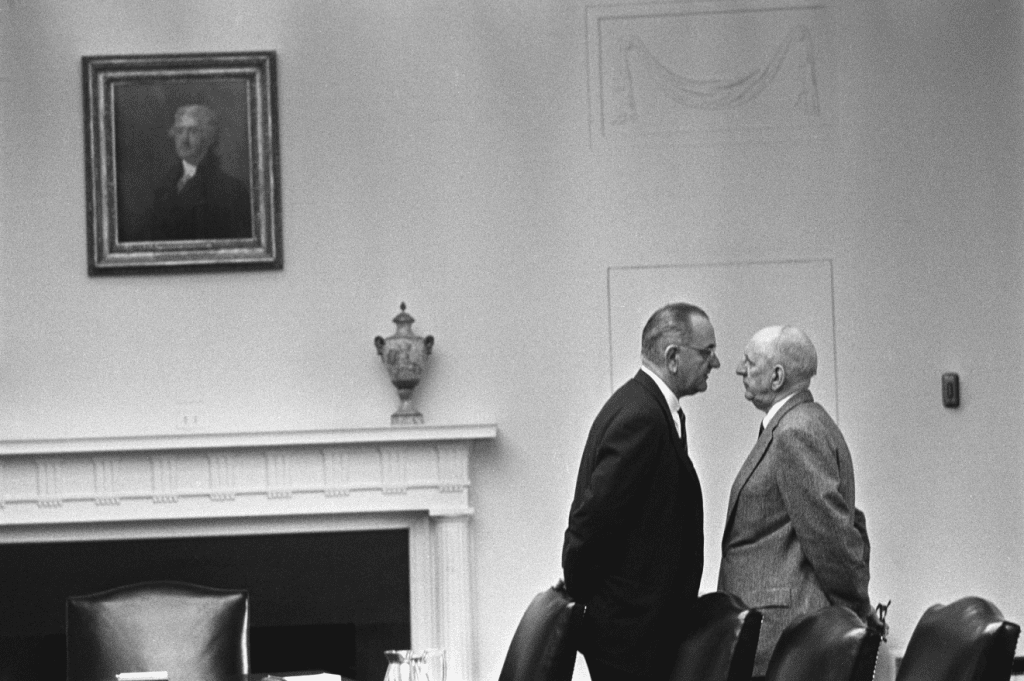

MAL: President Johnson gets a lot of credit for his remarkable persuasive skills. He is rightfully credited with his use of the “Johnson treatment,” his signature blend of flattery, hard bargaining, stubbornness, and threats, to get what he wanted from Congress. Yet I think historians and commentators have often exaggerated the importance of these methods.

To an extent that has often gone unrecognized, LBJ was pushing on an open door in the early 1960s in advocating bold social reforms. These years were, after all, the heyday of postwar American liberalism, when large swaths of the American public expressed strong confidence in government and no challenge – whether putting a man on the moon or ending poverty – seemed beyond the capabilities of such a rich and sophisticated society. I think a President Kennedy, Symington, or Humphrey, would have achieved much of what LBJ accomplished in the 1960s.

[Editor’s note: Like LBJ, Missouri senator Stuart Symington and Minnesota senator Hubert Humphrey competed against John F. Kennedy for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1960. Humphrey would later serve as Johnson’s vice president and became the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate in 1968, losing the general election to Richard Nixon.]

It’s hard to imagine a political backdrop more different from the one that prevails in our poisonously polarized society. President Biden is often likened to LBJ because of striking parallels in their careers, similar commitments to bipartisanship, and eagerness for transformative domestic agendas. Yet President Biden faces infinitely less propitious political conditions than those inherited by LBJ when he entered the White House. President Johnson enjoyed huge Democratic majorities in Congress as well as a gigantic mandate following his sweeping victory in the 1964 presidential election. Additionally, the Republican Party contained a strong liberal wing willing to work with LBJ on a variety of issues, including civil rights. (We sometimes forget that Congress approved the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act with higher percentages of Republican than Democratic votes in both houses.) President Biden enjoys none of these advantages.

NEP: As you noted earlier, the Johnson Administration committed itself to realizing an extraordinarily ambitious civil rights agenda. Yet LBJ himself espoused racist views. How should we untangle this paradox?

MAL: Lyndon Johnson was indisputably a man of the South accustomed to segregation and everyday racism. He used racist turns of phrase and held an honored place among Southern leaders dedicated to upholding racial separation. So it’s a real puzzle to understand how the LBJ became a crucial ally of the civil rights movement and surely the most important president since Abraham Lincoln in advancing the cause of Black freedom.

I’d offer three explanations to reconcile these contradictory aspects of LBJ. First, LBJ was never a doctrinaire racist like many of his Southern colleagues. While he could certainly speak in the ugly idiom of Jim Crow, he showed unusual empathy for African Americans at many points of his life and exuded a genuine sense of compassion for Blacks and other disadvantaged populations. In 1928, for example, he empathized with his Mexican American students during a stint as a teacher in Cotulla, Texas. In the 1930s, he created unusual opportunities for African Americans through his leadership of the Texas branch of a New Deal Agency called the National Youth Administration. By the time LBJ became president, then, his trajectory on race issues was different from that of many Southern politicians.

Second, LBJ was first and foremost a politician – a man capable of shaping and reshaping his positions as the public mood shifted. As a member of the House and Senate during the 30s, 40s, and 50s, Johnson downplayed his compassion for racial minorities in order to preserve his viability as a politician from a state firmly anchored in old racial hierarchies. Above all, LBJ tied himself firmly to the white South during his run for the Senate in 1948 and the early years of his Senate career. To do otherwise would have endangered his political career. The changing dynamics surrounding race in the later 50s and 1960s encouraged LBJ to reshape his image on the issue.

Third, LBJ’s thinking about race evolved as his life advanced. True, he held relatively unconventional ideas from his childhood, the result of growing up in a part of Texas where few African Americans lived. But Johnson’s ideas about race and civil rights changed enormously in the 1950s and 1960s as the civil rights issue surged to the forefront of American political life. By 1964 and 1965, he spoke in ways that demonstrate, at least to my ear, a dedication to the cause and a willingness to run political risks on behalf of racial justice that went well beyond his attitudes in earlier phases of his life.

NEP: It’s impossible to talk about LBJ without talking about Vietnam. As an historian of the Vietnam War, how do you assess President Johnson’s role in that conflict?

MAL: Some commentary sympathetic to LBJ tends to argue that he simply inherited the Vietnam War from his predecessors. How could he have deviated from the path once the United States had committed itself to the fight? I’m not so sure this is a helpful way to understand LBJ’s decision-making. When he took office, about 16,700 American personnel were stationed in Vietnam to advise the South Vietnamese armed forces. When he left office, more than half a million were waging a major war. Clearly, Lyndon Johnson made key decisions to commit the United States fully to the fight. Abundant evidence makes clear that he did so despite keen awareness of the problems that US forces would confront.

The key question, of course, is why did he make the decisions for war? As with the question above, I’d offer three answers. For one thing, LBJ, for all his inventiveness and iconoclasm in domestic policy, was rather conventional in his thinking about foreign affairs. He readily accepted Cold War verities about the need to contain communist expansion and the danger of falling dominos if the United States failed anywhere, even in a remote place like Vietnam. Although an array of journalists, policymakers, members of Congress, and foreign leaders urged LBJ weigh alternatives to a big war, he saw no real choice.

Second, LBJ believed that he needed to prevent a communist takeover of South Vietnam in order to protect his ambitious domestic agenda. The president worried, in other words, that a communist victory would expose him to fierce political attack for failing to guard American national security, killing his chances of rallying Congress behind programs like civil rights, Medicare, and the War on Poverty. To LBJ, the war in Vietnam was a cost of building the Great Society.

Third, LBJ decided to fight for reasons of his own personality. Deeply invested in his reputation as a can-do man who never backed down in the face of challenges, LBJ was unwilling – or perhaps even unable – to absorb the blow to his image that would have come with settling for something less than victory in Vietnam. By 1965, the only way to achieve that goal was to commit American forces to the fight.

NEP: How do you reconcile President Johnson’s very different foreign and domestic political legacies? Is it true, as is often said, that LBJ knew and cared about domestic politics but not foreign policy? Did his presidency suffer as a result?

MAL: One way to reconcile LBJ’s contrasting legacies in domestic and foreign affairs is to suggest that he simply cared more about – and was far more adept with – the former than the latter. He poured energy and ingenuity in his dream of reforming American society while behaving unimaginatively on the global stage. I’ve argued in this vein in my most recent book, suggesting that LBJ sought to avoid new controversies and embroilments abroad so that he could keep Congress and the American public focused on domestic reform. The bitter irony was, of course, that LBJ’s presidency would nevertheless be consumed by a foreign war.

There is, though, another way to reconcile LBJ’s domestic and foreign legacies – a way that emphasizes parallels, rather than differences, between Johnson’s efforts at home and abroad. In both arenas, one might argue, Johnson aimed to use the massive the massive power and know-how of the U. S. government to promote positive change. Domestically, this impulse entailed efforts to undo segregation, fight poverty, expand health care, reform education, and so forth. In the international field, this impulse involved promoting political and economic reform in poor societies around the globe and, if necessary, fighting the communist forces that stood in the way of democratic-capitalist development. The failure of the latter vision is easy to see. During LBJ’s presidency, the United States ushered in or bolstered ties with numerous authoritarian regimes, while Washington’s efforts to foster political and economic advances in South Vietnam failed spectacularly. But something broadly similar happened in the domestic arena. The administration’s social-reform programs undeniably produced permanent advances on race relations and other matters, but it encountered growing public and congressional skepticism during its final years in office. In the 1970s and 1980s, moreover, Americans increasingly accepted the conservative critique of the Great Society as a costly, intrusive, and ultimately ineffective expansion of federal power at the expense of individual freedom.

On the whole, then, we might conclude that LBJ embodied the failures of a generation that placed enormous faith in the capabilities of government to solve problems, only to realize the limits on those capabilities not only internationally but also at home.

NEP: So what lessons, if any, can contemporary political leaders—in this country or elsewhere—learn from LBJ?

MAL: They can certainly learn the dangers of overconfidence in American power. Of course, we’ve also learned this lesson more recently in Iraq and Afghanistan. But Lyndon Johnson still stands out as perhaps the most striking embodiment of faith in Washington’s capacity to fix what ails the nation or the world. Experience has taught us the difficulties of using even vast American power to beneficial effect.

But I think that the most important lesson that LBJ teaches us is a more positive one. He shows us the value of political pragmatism, bipartisan problem-solving, and a willingness to change one’s mind. In an era that prizes ideological purity, it’s good to recall what’s possible when pragmatically minded leaders work together to address real problems. LBJ’s efforts did not result in the perfect solutions that his rhetoric sometimes seemed to promise, but they indisputably pushed the nation down a constructive path that expanded individual rights and economic opportunity.

Mark Atwood Lawrence is Director of the Johnson Presidential Library and Professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin. His most recent book is The End of Ambition: The United States and the Third World in the Vietnam Era, published by Princeton University Press in 2021. Lawrence is also author of Assuming the Burden: Europe and the American Commitment to War in Vietnam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), which won the Paul Birdsall Prize for European military and strategic history and the George Louis Beer Prize for European international history, and The Vietnam War: A Concise International History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), which was selected by the History Book Club and the Military History Book Club. His essays and reviews have appeared in the New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Foreign Affairs, and Commentary. He has published several edited and co-edited books, as well as numerous articles, chapters, and reviews on various aspects of the history of U. S. foreign relations.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.