In Radio for the Millions, Isabel Alonso provides a captivating history of radio that sits at the intersection of sound studies, cultural history, and the politics of nationalism in modern South Asia. In this virtuosic tale, we read about the policymakers, artists, singers, political figures, and poets who inhabited a broader transnational space in South Asia. Using relatively neglected sources, as well as the usual range of newspapers, advertisements, posters, and memoirs, the book is pioneering in making radio the object of historical analysis.

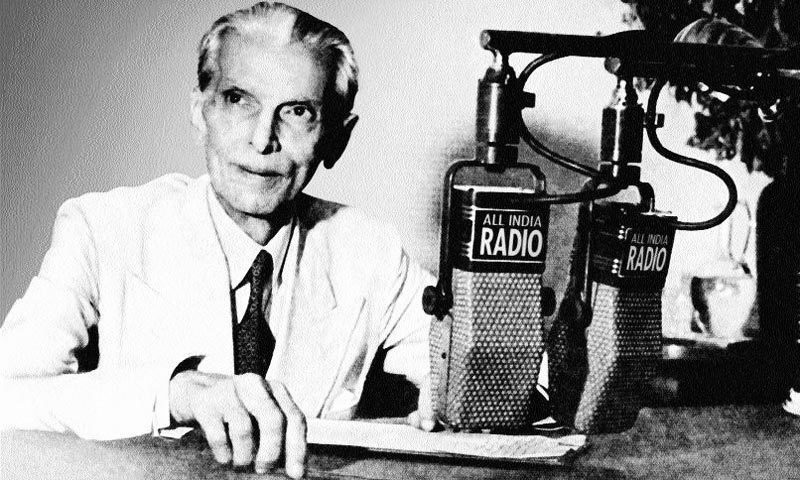

Readers learn that radio played a vibrant role in forging political subjectivities and mobilizing identities during the anti-colonial struggles of the twentieth century. It also created an aura around political figures. It was through the radio that the nationalist activist Subhas Chandra Bose remained a captivating figure and loomed large in the imagination of the listeners.

The history of rumors constitutes another fascinating aspect of this book’s narrative. Rumors about Bose, Radio Ceylon and its competitive relationship with All India Radio, the India-Pakistan war of 1965, and—last but not least—the famous singer Nur Jehan all constitute this larger fascinating arena of historical analysis.

Though the author does not identify her work as a contribution to ethnomusicology, her sensitivity to the place of music in a broader spectrum of sociability makes the book even more remarkable. Theoretically, following an Adornoian tradition, the literature around music in radio’s history has focused almost exclusively on radio’s role in promoting popular music and the notion of regression of listening. According to this theoretical tradition, radio and the popular industry made listeners passive consumers of the popular industry’s product. As a result, the relationship between the radio and the listeners is narrativized in a suspicious mode. This cynical approach towards radio has informed the historiographies of radio and sound in various contexts from the global South. In Iranian historiographies of radio, for instance, this Adornoian theoretical metanarrative has loomed large.

Alonso disrupts this tradition by focusing on the Director of All India Radio, B. V. Keskar, and his attempts to use radio to inculcate “discerning listeners.” The book shows how the newly independent Indian state considered radio the medium for developing “classical” tastes in Indian audiences. Keskar’s unease with popular culture marks an exciting point of departure for the revision of radio’s history globally. As Alonso’s work masterfully shows, “the citizen listeners” of radio – however briefly – became the subject of the elite’s cultural and artistic sensibilities, which at times sharply contrasted with that of the popular industry. In placing sound at the cusp of politics, nationalism, and identity, the author does not fall into the theoretical jargon sometimes associated with sound studies. While the book is theoretically informed and engaging, it is a situated historical work that brings sustained conceptual insights. Following Manan Ahmad’s work, the author argues for a transnational history of sound and sonic experience. The ‘soundscape’ of her book transcends the territorial limits of the nation-state.

In a similar vein, Alonso’s coinage of the term “citizen listeners” gestures at a collectivity of listening subjects. The citizens of newly independent India (and Pakistan) became also citizen subjects through programs that were mediated via transmitters. Rich in its narrative and coverage of various aspects of sound, Radio for the Millions opens numerous interesting avenues for further investigation. For instance, we can certainly wonder about the ways in which listening “citizen subjects” thought about the sounds they heard on the radio and acted to shape the programming beyond writing letters.

This book will benefit an expansive community of readers, including academic communities in the disciplines of history and ethnomusicology and specifically readers interested in the cultural history of sound and music. It provides a wonderful model of the cultural history of sound and music for other societies, especially modern Iran, where writing cultural histories of sound and listening has been an arduous task.

Pouya Nekouei is a Ph.D. student in Middle Eastern history at the department of Middle Eastern studies at the University of Texas, Austin. His research interests pertain to the social and cultural history of Iran, the Indian Ocean world, and the connected social and cultural history of South Asia, Iran, and Europe.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.