Introduction by John Gleb

In February 1979, a popular revolution in Iran overthrew the authoritarian government of Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, a key ally of the United States. Ten months later, on November 4th, 1979, Iranian college students demonstrating against U. S. support for the Shah seized control of the U. S. embassy compound in Tehran, taking fifty-two U. S. diplomats, embassy workers, and compound guards hostage. The students held the hostages prisoner for the next 444 days.

The Iran Hostage Crisis was acutely embarrassing to the administration of embattled U. S. president Jimmy Carter. As a result, it became a major domestic political issue during the 1980 presidential election campaign, in which Carter, a Democrat, tried to fend off a challenge from Republican rival Ronald Reagan. Carter ultimately lost the election. Two months later, in January 1981, U. S. diplomats and Iranian officials reached an agreement that secured the release of the hostages. The hostages left Iran on January 20th, 1981, the same day Reagan assumed office.

Over the course of the last four decades, journalists and members of Congress have repeatedly investigated allegations that members of the Reagan campaign contacted or colluded with Iranian officials to prevent the release of the hostages prior to the 1980 election–an event that would have constituted an “October surprise” favorable to Carter. None of the allegations have been conclusively substantiated. However, one of them made national headlines earlier this year. Its source is Ben Barnes, a former Lieutenant Governor of Texas who worked alongside former state governor John Connally to support Reagan’s 1980 presidential campaign. In a March 2023 interview published by the New York Times, Barnes claimed that Connally, working through intermediaries in the Middle East, had attempted to persuade Iranian officials not to release the U. S. embassy hostages prior to the general election.

As the Times notes, Barnes’ allegation is hard to verify or disprove in the absence of fresh documentary evidence. But if the allegation is true, is it also consequential? Several years before he spoke to the Times, Barnes told his story to H. W. Brands, a distinguished historian at the University of Texas at Austin. Brands included the story in his recently-published biography of Ronald Reagan. However, he declined to place Barnes, Connally, or their alleged co-conspirators close to the center of his book’s main narrative. In the article below, Brands explains why.

This article was originally published as part of “A User’s Guide to History,” H. W. Brands’ Substack newsletter. Images have been added by Not Even Past.

Ten years ago I was researching a biography of Ronald Reagan. I had gone through the available written records at the Reagan Library in California and other archives and was interviewing people who had known Reagan. I ran into Ben Barnes, a former lieutenant governor of Texas and a generally well-connected political person, and casually asked if he had had any dealings with Reagan.

Barnes proceeded to tell me about a trip he had taken during the summer of 1980 with John Connally to the Middle East. Connally was a former governor of Texas, former secretary of the Treasury, former Democrat, and recent unsuccessful candidate for the Republican nomination for president. Connally had his eye on a job in a Reagan administration, should the Reagan campaign against Jimmy Carter succeed. Secretary of state was the one he wanted, and a Middle Eastern trip would burnish his foreign-policy credentials.

The trip had another purpose, as Barnes volunteered to me. A principal allegation of the Reagan campaign was that Carter was a weak leader, as witnessed by his inability to effect the release of several dozen American hostages held in Iran since the previous November. The Reagan campaign, headed by William Casey, was worried that events would prove their allegation wrong: to wit, that negotiations to free the hostages would succeed. This “October surprise” might negate Reagan’s lead in the polls and allow Carter to defeat him.

Barnes related that during their Middle East trip, Connally told government officials in Israel and several Arab countries that it would “not be helpful”—Barnes’s paraphrase of Connally—for the hostages to be released before the November election. I asked Barnes if Casey had told Connally to convey that message. Barnes said he wasn’t informed and didn’t ask.

I included this account in my Reagan book, published in 2015. I was somewhat disappointed that it didn’t receive much attention. But only somewhat. I didn’t draw particular attention to the story, rather embedding it in a longer telling of the allegations and investigations of the October Surprise since rumors had first surfaced during the campaign itself. (The affair was called October Surprise despite the conspicuous absence of the surprise the Reagan team feared.) And my longer telling started only at page 231 of a very long book on Reagan’s life.

The Barnes part was not even the most consequential piece of the story. Among the allegations aired early was a claim that Casey had met some Iranian operatives at a hotel in Madrid. Efforts by congressional investigators in the 1990s to track this down failed in the face of suspiciously missing files in the papers of Casey, by this time deceased. Eventually, though, a State Department memo at the George H. W. Bush Library confirmed the presence of Casey in Madrid—”for purposes unknown”—at the time the meeting with the Iranian middlemen was said to have occurred.

All this made a strong circumstantial case that the Reagan campaign was meddling in the efforts of the Carter administration to obtain the release of the hostages. If true, this would have been a violation of the Logan Act, a 1790s statue forbidding precisely such free-lancing by private individuals in the affairs of state. But the evidence was only circumstantial. Casey was beyond prosecution anyway.

Perhaps more important in diminishing the impact of my revelation was the circumstance that the Watergate scandal had raised the bar for proof of allegations of misbehavior at the highest levels. Watergate climaxed with discovery of a “smoking gun”: the tape recordings of Nixon in the act of obstructing justice. No such smoking gun had been found regarding Casey and the October Surprise allegations.

No less crucial was that the principals were untouchable. Casey was dead and Reagan had slipped into the fog of dementia. Tarnishing Reagan’s reputation—especially after the Cold War had ended, largely on Reagan’s terms—would have been perceived by many as beating up on a helpless old man who otherwise had done great things for the country and the world.

Lastly, none of the evidence touched Reagan himself. I did uncover a memo in the Connally papers at the Lyndon Johnson Library indicating that Connally spoke to Reagan during the Middle Eastern trip. But it contained no indication as to what was said.

What seems most likely to me is that Casey was working on his own. When he became Reagan’s head of the CIA, he was notorious for doing things he didn’t tell his boss about. Reagan knew Casey’s modus operandi; this was why he was hired for both jobs: running the campaign and running the CIA. The distancing allowed Reagan plausible deniability in the event Casey got caught. You can fire a campaign manager or CIA director; firing a candidate or a president is harder.

There was one other reason I didn’t put the shenanigans of the 1980 campaign on page 1 of my book: They didn’t change anything about the election.

The hostage-holders hated and feared Carter. The trigger for the capture of the hostages was Carter’s decision to allow the former shah of Iran to come to America for medical treatment. Iranian radicals—and some moderates, too—thought this was a ruse and that Carter was conniving to restore the shah to power, as Dwight Eisenhower had done a quarter-century before. The hostages were insurance against any such scheme. By October 1980, the chances of a restoration were slim, but the Iranians had no desire to see Carter reelected. They weren’t about to boost his chances.

In essence, Casey seems to have been urging the Iranians not to do something they had no intention of doing anyway. So while the October Surprise story revealed something about the sleazy conduct of American political campaigns, it almost certainly had no effect on the broader course of history.

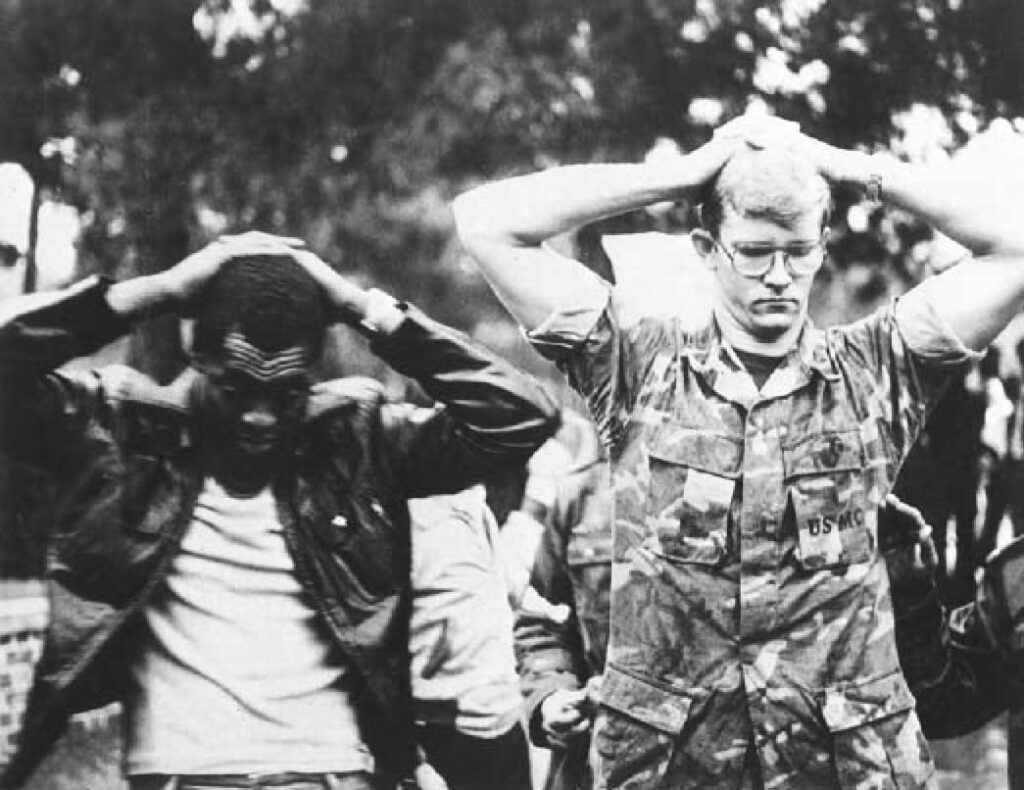

One of the hostages himself said as much. The story resurfaced last Sunday when the New York Times featured an article by Peter Baker about Ben Barnes and his part in the affair. The article attracted attention, leading to much finger-pointing and chin-tugging. As a follow-up, another Times reporter, Michael Levenson, contacted some of the surviving hostages. Kevin Hermening had been a Marine guard at the U.S. embassy at the time of the seizure. “The Iranians were very clear that they were not going to release us while President Carter was in office,” Hermening said. “He was despised by the mullahs and those people who followed the Ayatollah.”

My Reagan book did pretty well in the marketplace. Would it have done better had I led with Ben Barnes and the October Surprise? Maybe. I’ve received more calls after the Peter Baker article, which mentions me and observes that I reported the story eight years ago, than I did at the time. My publisher doubtless would have been happy had all the attention occurred around the publishing.

Yet in the end I’m okay with how things turned out. The story is splashy but not really consequential. The life of Reagan is a bigger deal than something that happened during his campaign for president and didn’t even affect that.

Page 231 was the right place, I still think.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.