History education has been under attack recently. Or, more specifically, efforts to accurately teach the painful, brutal history of slavery are under attack. Teaching the hard history of slavery has long been a problem in American classrooms. Recently, the battle over state curriculum standards has intensified as some seek to revive a version of history popularized by the Lost Cause narrative. According to this view, which was popular until the 1950s, enslavement served as a “civilizing force,” one that capitalized on enslaved people’s natural dispositions, but ultimately benefited enslaved people.[1] Proponents of the Lost Cause insisted that the plantation served as a “school” in which enslaved people learned to assimilate and ultimately prospered.[2] Promoters of this discourse thus argue that slavery was a positive good, that it was a paternalistic, benevolent system in which enslaved people were content. Sound familiar? It probably should.

The new African American history learning standards adopted by Florida’s Department of Education have made national headlines and elicited strong reactions from educators and historians. One of the standards in question, requires that teachers and students “Examine the various duties and trades performed by slaves (e.g., agricultural work, painting, carpentry, tailoring, domestic service, blacksmithing, transportation).” While at first glance, the learning objective appears innocuous, the “Benchmark Clarifications” that follow seem to align Florida’s new standards closely with the Lost Cause insistence that slavery was a positive institution. It states that “[i]nstruction includes how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”[3] Under these new standards, Florida middle school students will learn that enslaved people benefited from their subjugation.

Pressed for clarification, members of the working group tasked with developing the new curriculum standards, Dr. William Allen and Frances Presley Rice, explained that, “[t]he intent of this particular benchmark clarification is to show that some slaves developed highly specialized trades from which they benefitted. This is factual and well documented.” Allen, professor emeritus of political science at Michigan State University, and Rice, a retired Army lieutenant colonel who holds a Juris Doctorate, offered specific examples, including “blacksmiths like Ned Cobb, Henry Blair, Lewis Latimer and John Henry; shoemakers like James Forten, Paul Cuffe and Betty Washington Lewis; fishing and shipping industry workers like Jupiter Hammon, John Chavis, William Whipper and Crispus Attucks; tailors like Elizabeth Keckley, James Thomas and Marietta Carter; and teachers like Betsey Stockton and Booker T. Washington.”[4]

The problem is that their examples are factually inaccurate. To start, only one of the seven men Allen and Rice identify was actually a slave.

Ned Cobb was born in 1885, twenty years after slavery had been outlawed by the 13th Amendment. Cobb was a tenant farmer from Alabama and an early member of the Sharecroppers Union; he may have learned his blacksmithing skills from his formerly enslaved father, but he is recognized as a leader in organizing farmers. Henry Blair patented a mechanical corn planter in 1834. Because enslaved people were not eligible to receive patents, it is likely that Blair was free.

Lewis Latimer was born in Massachusetts—his enslaved parents escaped Virginia at least six years before he was born. James Forten was a free man who worked as a sail maker in Philadelphia. Paul Cuffe was also a free man. He worked as a whaler. John Chavis was born free and worked as a teacher and minister. Although William Whipper’s mother was enslaved, Whipper was born free in Pennsylvania in 1804. Betty Washington Lewis, George Washington’s younger sister, is a white woman who owned enslaved people. Booker T. Washington is the only person Rice and Allen correctly identified as having been enslaved. Washington was nine years old when slavery ended—after emancipation, he labored in a salt furnace during the day and taught himself how to read at night. Washington did not learn this life-changing skill while enslaved because, in southern slave states, it was illegal to teach enslaved people how to read and write.

In truth, most newly emancipated people found it difficult to find work that didn’t involve continuing to toil in the South’s cotton fields or as domestic workers, or menial jobs. Even skilled craftsman often failed to find work utilizing those skills because they lacked the tools to pursue that work on their own.

Allen and Rice advocate for a distorted, myopic version of slavery. And, they don’t seem especially interested in getting their history right. Instead their claims appear to connect directly to Lost Cause narratives that were dominant decades earlier. And that project was in the end about providing the intellectual foundation for sustaining white supremacy.

If state standards provide little insight into the realities of slavery, where can teachers turn?

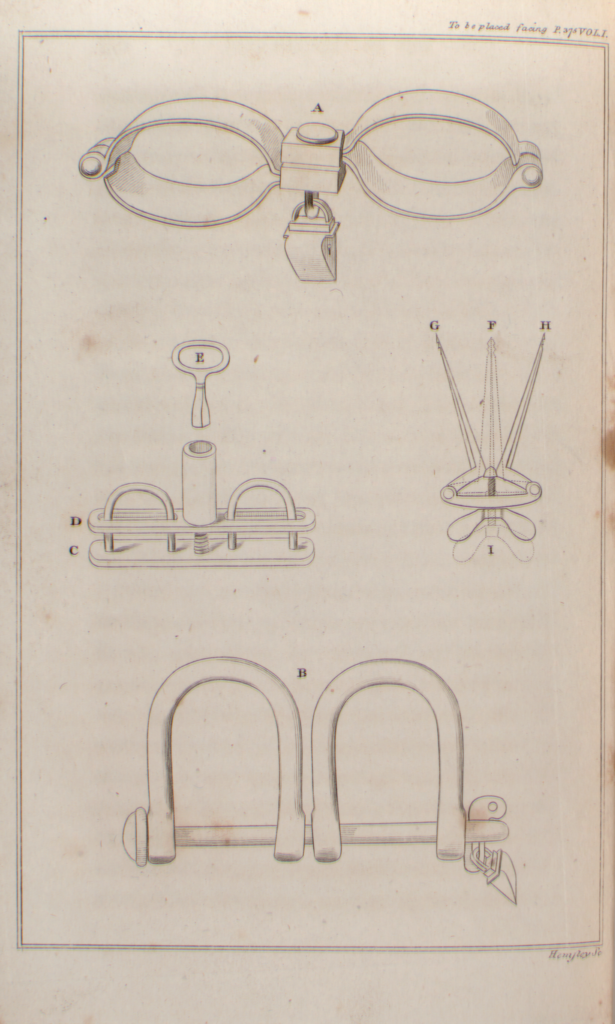

“Untitled Image (Iron Shackles)”, Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora, accessed August 28, 2023, http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/2619

Teaching about slavery is difficult and some teachers struggle to do it well.

In 2018, fourth graders in Wisconsin, were asked to identify “3 good reasons for slavery.”[5] The previous year, eighth grade students in California had their wrists taped together and were forced to lie in rows in a darkened room and watch clips from Roots as part of a lesson in which they role-played enslaved people onboard ships during the Middle Passage. Their teachers acted as ships’ captains.[6] These are not isolated incidents.

Across the country teachers use experiential lessons or role-playing simulations in which students participate in mock slave auctions, clean cotton, imagine themselves as slaves, craft advertisements for runaway slaves, or simulate escape on the Underground Railroad by running through the woods and wading through frigid water, as do students in Minnesota, in order to “learn” about slavery.[7] These examples illustrate the broader truth documented in a 2018 report commissioned by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), that just over half of the 1,700 teachers surveyed said they “feel competent” to teach about slavery—which means that almost half do not. Sixty percent of teachers surveyed find their textbooks inadequate, and 40% think that their school districts do not provide sufficient resources to teach about slavery.[8] That was before Florida and other states rolled out new standards that seem to be informed more by ideology than by historical fact.

It is not surprising then that only 55% of teachers teach about the “diverse experiences of enslaved persons,” and fewer still teach about “the continuing legacy of slavery” today. As teachers struggle to represent the horrors of slavery accurately, public school students pay the price; few learn about the history of slavery, and many learn lessons that have to be unlearned—or that should be. The SPLC report concluded that the United States “needs an intervention in the ways that we teach and learn about the history of American slavery.”

The challenge that teachers face is aggravated by a lack of primary sources. The teaching of slavery often centers on documents and accounts created by the enslavers rather than by enslaved people themselves. Plantation records document the productive and reproductive labor enslaved people were forced to perform. Slave auction broadsides, runaway advertisements, wills, deeds, and mortgages attest to their commodification—all from the perspective and through the voices of their enslavers.

Federal census records reduced enslaved people to hash marks or a set of physical descriptors recording their gender, age, and color—Female, 17, Black—reflecting their status as property, not people. There are no records of their marriages, no birth or baptismal records for their children, and frequently even their deaths went unmentioned. This erasure from the historical record means that the lives of the enslaved remain largely unknown and their stories of separation and struggle untold.

So, how can teachers overcome these obstacles?

One way is to find sources that reveal more about the lived experiences of enslaved people. One of the most ubiquitous experiences for enslaved people was being sold—and thus being separated from their family and communities. Teaching about slavery through the lens of the domestic slave trade and family separation provides teachers opportunities to talk about topics such as westward expansion, the growth of the plantation economy in the South, the economic aspects of slavery, and regional differences. It also provides teachers a way to interrogate the long-lasting impact of enslavement on enslaved people and families—to situate attempts to put their families back together within the historical context of Reconstruction—to think about Reconstruction as an individual experience and a national endeavor.

Too often discussions about slavery end in 1865. What happened next? What did newly freed people do after emancipation? Did they prioritize finding work or a new place to live? Did they pursue an education? Or did they begin a search for their family? Asking these questions enables students to examine multiple possibilities. It helps students understand the overwhelming obstacles freed people faced. It also allows students to consider formerly enslaved people’s enduring hope to be reunited with their loved ones—to make their experiences personal and relatable to students in ways that are not possible when only thinking about slavery as an economic institution in the context of the cotton boom.

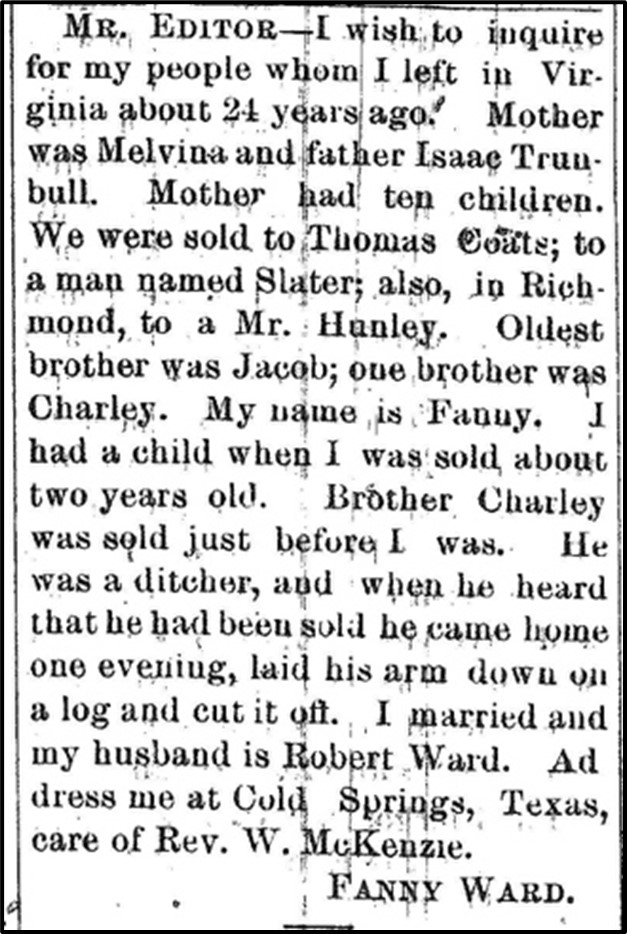

Last Seen advertisements are just such sources.[9] Formerly enslaved people took to the papers after emancipation to search for loved ones. They placed ads in Black-owned newspapers across the country describing their family histories, the last known locations of loved ones, former enslavers’ names, and countless moments of separation and sale.

Let’s look at one such ad and examine how teachers might use it in their classrooms.

Fanny Ward’s 1883 advertisement (above) appeared as an appeal to the editor of the Southwestern Christian Advocate, an African American newspaper published in New Orleans. Scholars use documents like this to examine a number of trends and patterns relevant to the study of slavery. But they also hold great potential for educators to teach about enslaved families, the domestic slave trade, and the effects of emancipation on Black families. This begins by challenging students to consider how slavery resulted in massive familial separation and how it left millions of Americans with a strong desire to reunite with loved ones. With help from the teaching resources available on the Last Seen website, teachers have access to the broader historical context that will help them to consider what it meant for Ms. Ward to have been sold away from her child when that child was only a toddler. Teachers can also ask students to think about Charley’s shocking act as a manifestation of the trauma endured by enslaved people who were repeatedly separated from their families.

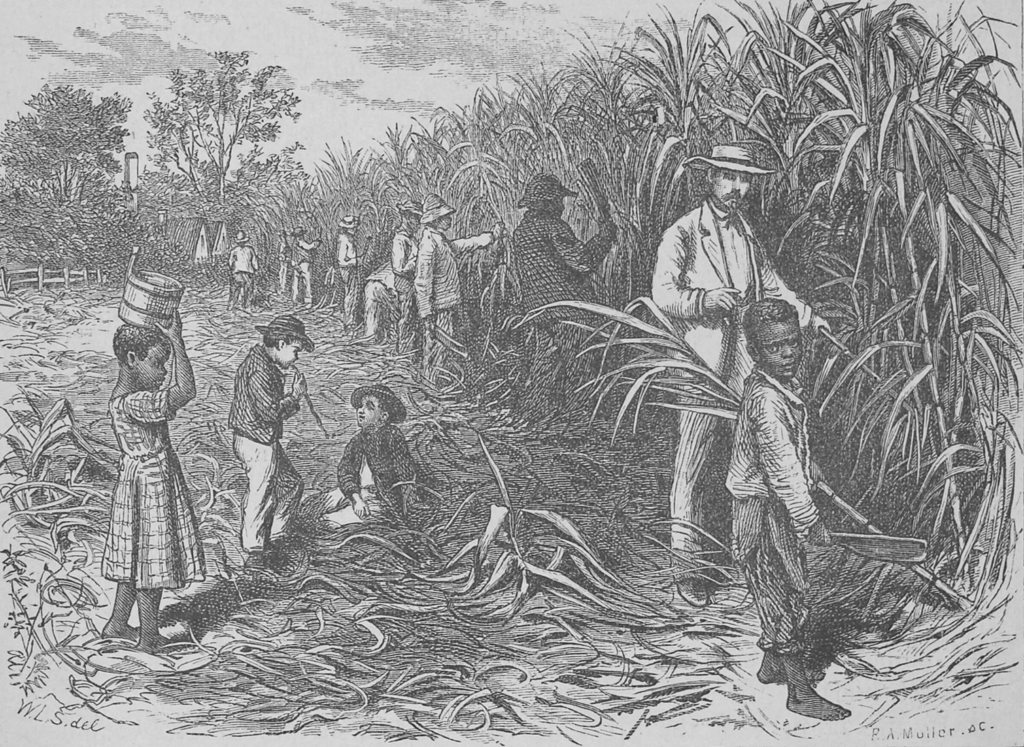

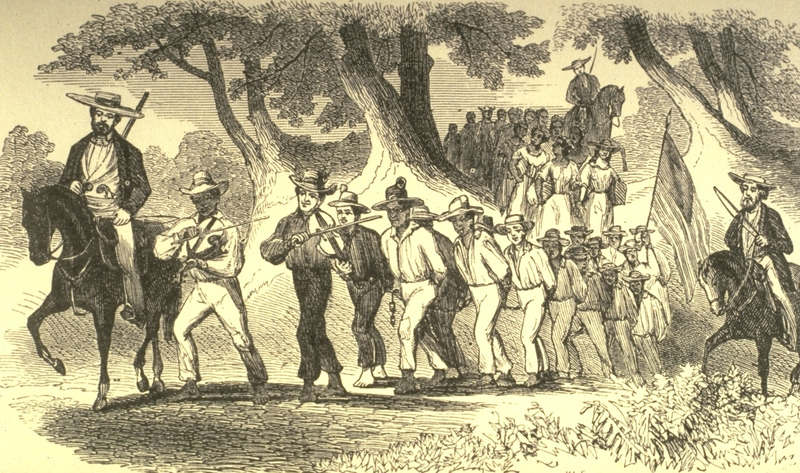

Consider the multiple ways teachers might use Fanny Ward’s ad.[10] Fanny’s story allows teachers to teach the differences between the Middle Passage and the Second Middle Passage, or the domestic slave trade (1820s-1860s). The latter was not a trans-Atlantic journey; when Fanny was sold away from her parents, siblings, and, perhaps, her own child, she likely walked most of the way from Virginia to Texas, chained to others in a group called a coffle. Fanny’s account enables teachers to put a human face on lessons about the nineteenth-century cotton production that fueled American capitalism and the market economy. How did these larger processes impact enslaved people? For countless young people like Fanny, it meant they were taken thousands of miles away from their families to pick cotton in fields owned by men like Coats, Slater, and Hunley. Most of them never saw their families again. The cotton they picked made its way to factories on America’s east coast and across the Atlantic to factories in England, where it was turned into cloth—the cheaper sort made its way back to America, used to make clothes for the enslaved.

To teach the ad, we start by doing a bit of math. The ad was placed in 1883 describing a separation that occurred twenty-four years ago; this means Fanny’s family—all twelve or thirteen of them—lived together until around 1859 (1883-24=1859). Students can go to the 1850/1860 census to find Thomas Coats, Slater, or Hunley in Richmond, Virginia—but they won’t find Fanny, her parents, and siblings there. Or at least not named. They were property not people. The census used in conjunction with this ad, though, can reveal critical information about the households in which Fanny lived. Was she a member of a large, enslaved community, or one of a few enslaved people within the enslaver’s household? What might students be able to infer about Fanny’s life based on each new community she became a part of? Further research into county records may reveal the broader enslaved community in which Fanny lived, allowing students to draw inferences and form conclusions about Fanny’s potential social interactions. Who she might have had a child with? Reading ex-slave narratives recorded through the Works Progress Administration offer students a glimpse into individual experiences of enslaved people in that community; doing so can help students extrapolate more details about Fanny’s life.

Teachers might use Fanny’s plea for help finding her family to introduce students to historical methods. Her ad underscores the challenges of following historical subjects whose circumstances allowed them to leave only the faintest trace in the records—in this case, eleven sentences that hold revealing clues about the fates of at least twelve people living through this moment in American history. In a classroom, a teacher might ask their students to think about when Fanny became free, what it meant for her to write her family history (or perhaps Reverend W. McKenzie helped her), and how historians pursue people who changed their names through historical records. For students, Fanny’s story allows them to see the strong emotional ties that she shared with her family; twenty-four years and thousands of miles later, she still hoped she would find them.

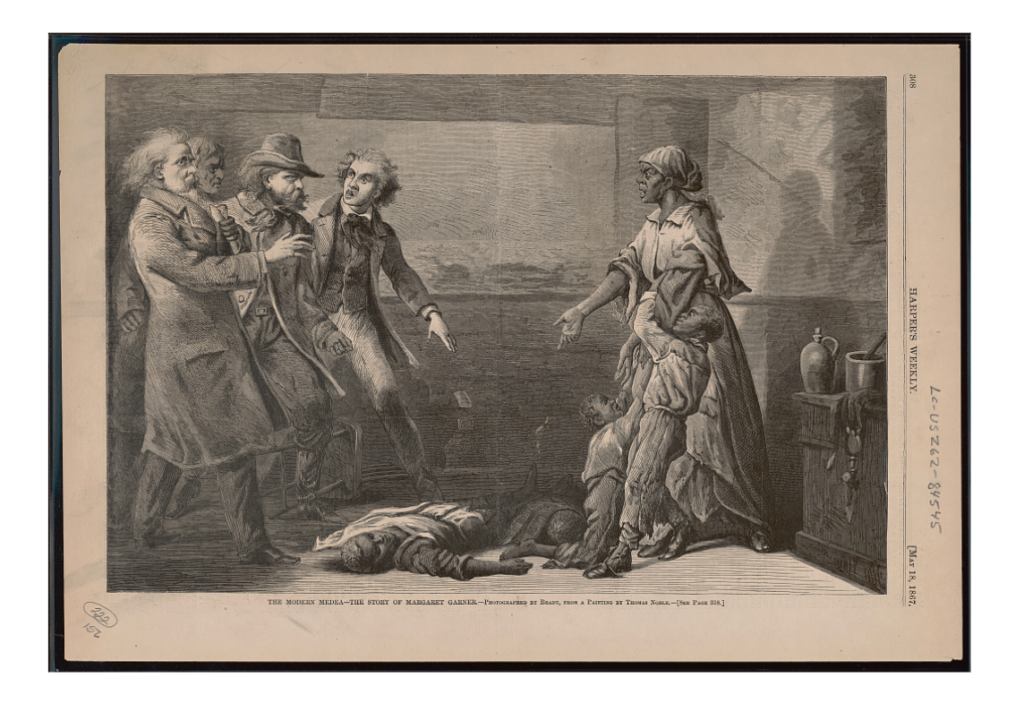

And, then, there is what this ad reveals about enslaved peoples’ resistance and how they were sometimes able to shape their own futures. Fanny’s brother Charley, described as “a ditcher…laid his arm down on a log and cut it off” when he learned that he too was going to be sold away from his family. This act of defiance likely thwarted Charley’s sale and the impending forced separation from his remaining family. Informed by modern psychological research, scholars have begun to pose the questions that may someday allow us to understand what Charley did and how Fanny lived with the trauma of losing her family. This aspect of the ad might be more difficult for teachers to teach, however, because it challenges students to consider the overt brutality of slavery, and in some instances, resistance. We don’t know if Charley succeeded in preventing his sale or whether he was punished for this act of self-harm. What we do know, is that his act of resistance, documented by Fanny in her ad, is likely the only place he appears in the historical record. Charley resisted what was a routine part of slavery—being separated from his family and those he loved. Informed by modern psychological research, scholars have begun to pose the questions that may someday allow us to understand what Charley did and how Fanny lived with the trauma of losing her family.[11] Fanny’s 1883 ad is one of thousands collected, published and now discoverable by teachers and students in the Last Seen collection.[12]

Teachers can use this ad to personalize the experience of enslavement, separation, and resistance. Too often textbooks and teaching materials treat slavery in impersonal terms—such as asking students to consider it as something that was both “good” and “bad.” Or they present slavery in terms of the labor enslaved people performed, the value of the cotton produced by enslaved hands, and how enslaved people made possible the growth of the cotton economy. When texts discuss resistance, they focus on big, spectacular examples, such as Nat Turner’s 1831 rebellion whose widespread social and political effects have been well-studied. But the ways that enslaved people resisted the institution in their every-day lives, the small and not-so-small ways that individual enslaved women and men refused the institution’s worst forms of dehumanization, have received far less attention—although they were much more common and consequential.

Charley’s singular act of resistance reflected his determination to remain with his family. Like Charley’s story, this ad reveals details about Fanny’s family that are available nowhere else. Of the ten children born to Fanny’s parents, Melvina and Isaac, she may not have been the only one to survive to have children of her own, if she did so. And, then, there is the child Fanny mentions in the ad, whom she was sold away from. This ad allows teachers and students to think carefully about enslaved motherhood, the forced separations of parents and children, and the particular forms of women’s resistance. Fanny was not only separated from her parents and siblings, she was likely also separated from her child—and conversely, her child was separated from their mother. What choices did Fanny have? How were they the same and different from Charley’s?

Beyond resistance, the other details of Fanny’s life offer students a number of opportunities to learn about the Second Middle Passage by researching the names and places in the ad. Fanny names three enslavers. Students can follow the list of white men who took away Melvina and Isaac’s children: “We were sold to Thomas Coats; to a man named Slater; also in Richmond, to a Mr. Hunley.” Each name is a bread crumb Fanny left behind that students can follow to learn more about this enslaved family, what they experienced in slavery, and whether and who among them survived.

All of this is possible because of the information found in this one ad. Using Fanny’s ad in conjunction with these additional primary sources enables students to become historians, to bring Fanny’s story to life. With the help of teachers trained on how to read Last Seen ads and use them in their classrooms, students can use various additional primary sources to fill in the picture of Fanny’s life and tell a history of slavery that places Fanny and others like her at the center. This is how we can begin to change how students understand the domestic slave trade, the family lives of enslaved people, and the long search for family after emancipation.

In short—perhaps the best way to teach about slavery is to actually teach about slavery—through the experiences of those who experienced it firsthand.

Signe Peterson Fourmy is an Assistant Professor of Instruction in the Department of History at UT Austin. She is also a Co-Primary Investigator for the NHPRC-funded project, Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery at Villanova University. Her research focuses on slavery, resistance, gender, and the law.

Sources:

[1] U.B. Phillips, American Negro Slavery: A Survey of the Supply, Employment and Control of Negro Labor As Determined by the Plantation Regime. (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1918), 339-344.

[2] Phillips, American Negro Slavery, 342.

[3] Florida’s State Academic Standards—Social Studies, 2023. Standard SS.68.AA.2.2. Accessed July 26, 2023. https://www.fldoe.org/core/fileparse.php/20653/urlt/6-4.pdf

[4] Antonio Planas, “New Florida standards teach students that some Black people benefited from slavery because it taught useful skills,” NBC News, July 20, 2023. Accessed July 21, 2023. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/new-florida-standards-teach-black-people-benefited-slavery-taught-usef-rcna95418

[5] Bret Lemoine, “Give 3 good reasons for slavery: 4th grade homework assignments sparks backlash, apology in Wauwatosa,” Fox News Milwaukee, January 10, 2018. https://www.fox6now.com/news/give-3-good-reasons-for-slavery-4th-grade-homework-assignment-sparks-backlash-apology-in-wauwatosa

[6] Anne Branigan, “Calif. High School Sparks Criticism for Using Slave-Ship Role-Play to Teach Students History,” The Root, September 18, 2017. https://www.theroot.com/calif-high-school-sparks-criticism-for-using-slave-shi-1818512323

[7] Valerie Strauss, “Don’t know much about history: A disturbing new report on how poorly schools teach slavery in schools,” The Washington Post, February 3, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2018/02/03/dont-know-much-about-history-a-disturbing-new-report-on-how-poorly-schools-teach-american-slavery/; Joe Helm, “Teaching America’s Truth,” The Washington Post, August 28, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2019/08/28/teaching-slavery-schools/; Julian Lucas, “Can Slavery Reenactments Set Us Free?” The New Yorker, February 17, 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/02/17/can-slavery-reenactments-set-us-free; N’dea Yancey-Bragg, “Mock slave auctions, racist lessons: How US history class often traumatizes, dehumanizes Black students, USA Today, March 2, 2021. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/education/2021/03/02/heres-why-racist-school-assignments-slavery-persist-u-s/4389945001/

[8] Kate Shuster, Teaching Hard History, Southern Poverty Law Center, January 31, 2018. https://www.splcenter.org/20180131/teaching-hard-history#part-i

[9] Full disclosure, I’ve worked on the Last Seen Project at Villanova University since September 2020.

[10] “Fanny Ward searching for her family,” Lost Friends Ad, Southwestern Christian Advocate (New Orleans, LA), September 13, 1883, Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery, http://informationwanted.org/items/show/2294.

[11] On trauma, see Kidada Williams, They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I, New York University Press, 2012; Saidya V. Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 26, no. 2 (2008), 1-14; Nell Painter, “Soul Murder and Slavery: Toward a Fully Loaded Cost Accounting,” Southern History Across the Color Line, Markhum Press Fund, 1995, 15-39.

[12] “Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery,” accessed August 18, 2023, https://www.informationwanted.org.

*In the banner, an enrollment list of slaves from Saline County, Mo., 1861-1865. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.