From the Editors: This is a new series designed to introduce the experience of studying History at college from the student’s perspective. It is designed to demystify the discipline and to make it more accessible to all students.

Whenever I tell someone I’ve just met that I’m a history major, they say something along the lines of “Oh, I could never do that, I hate history.” That’s fair enough. Not everything is for everyone; I have little interest in differential equations. But this distaste for history often stems, in fact, from a fundamental misunderstanding of what studying history actually is. Middle and high school history classes are designed to make everyone literate in history; they are not meant to teach someone how to be a historian.”. The result is that many people have a distorted view of what it means to actually study history. In the first article of a planned longer series, I want to dispel these misconceptions and talk about what history classes in college are actually like, what skills studying history teaches, and the kind of work history students do.

First, a disclaimer. I’ve only taken history classes at the University of Texas at Austin, and while I’ve looked over many other universities’ degree plans and requirements, and I want this series to be as generally applicable as possible, some details may be different from university to university. If you have any specific questions, email the university’s history advisors. They’re very friendly, and they want you to succeed.

To answer everyone’s first question, studying history is not memorizing names and dates. Perhaps I shouldn’t confess this, and I apologize to any of my professors who are reading this, but I don’t really know the exact date of almost any of the events I’ve studied. That’s something that high school history classes focus on because it’s easy to turn the day of, say, the Pearl Harbor attack into a multiple-choice question: “What day was the attack on Pearl Harbor?”. Now, don’t get me wrong, you still need to know when some things happened, usually what year, but the order of events is far more important. “What political decisions did Japan and the United States make leading up to the attack on Pearl Harbor?” is a question that takes much longer to answer and is much more difficult to turn into a multiple-choice question than the exact date.

But, of course, that question is also far more interesting and indeed significant. The Japanese government’s desire to secure their flanks from a surprise attack by the United States while they pushed further into China, the American oil embargo on Japan, and the invention of the Japanese long-range attack fighter A6M Zero may have made some kind of attack inevitable. Or perhaps it did not. Delving into questions like this is the point of studying history. The complex interplay between different social, economic, and political (to name a few) factors, not to mention the ever-present element of flawed human decision-making, cannot easily be distilled down to fit a standardized test. When your 10th-grade AP World History course has to cover literally all of human existence from the emergence of the first Homo erectus to the present, it only makes sense that they will have to leave some things out.

Second, history classes are not typically big lectures where you listen to a single teacher tell you what happened, memorize that, and repeat it back to them. Don’t get me wrong: some history classes are lectures, especially survey courses for freshmen and sophomores, designed to give a shallow overview of a wide topic, but the vast majority include some element of discussion. Your college isn’t going to want to give you a history degree because a professor made you memorize some facts about ancient Rome. They want you to interrogate the sources, discuss your conclusions with your peers, and become a well-rounded citizen capable of engaging across different levels. The best classes I took were not in massive 250-student lecture halls but smaller 20-person seminars where everyone had an equal opportunity to share their ideas.

If history classes are not about memorizing dates and facts as dictated by a dispassionate lecturer, then what are they? Well, in fact, they are not too dissimilar from literature courses. Let me explain what I mean. Most days, when you attend a history class, you’ve already done most of the work. Before every class session, there will be some assigned reading, usually from a primary source relevant to what you’re learning in class. You’ll then show up to class, the professor will have a short presentation, usually to provide some additional context, and then they will ask some open-ended questions for you and your classmates to discuss. Things like “What does this remind you of?” or “What is the author getting at?” This is the same way that literature classes work. If you take a Shakespeare class, you’ll have to do the same thing: read an act or two of Two Noble Kinsmen and show up to class ready to discuss.

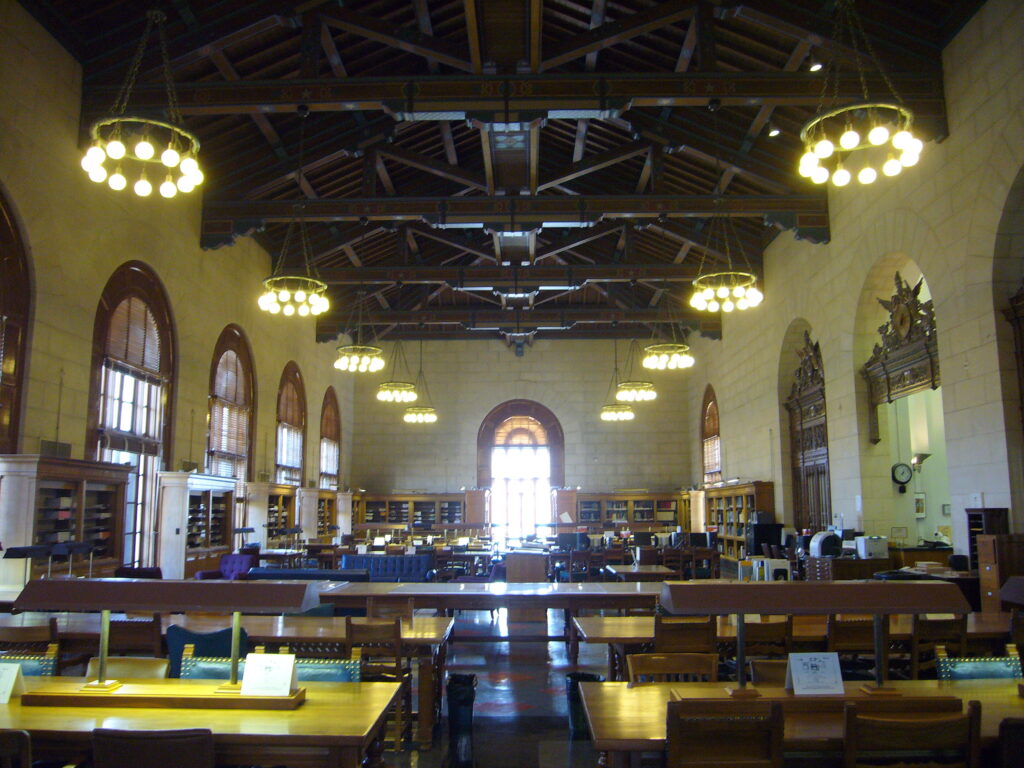

As for assignments, mercifully, worksheets are gone. In most history classes, you’ll only have a handful of things that you actually turn in for a grade. This is in contrast to STEM classes, which have pretty consistent, sometimes daily, homework to turn in. Most assignments are some kind of written essay, and the prompts are usually as open-ended as discussion classes. I’ve had essays focused on topics like how to define the word “secularism,” give an overview of some moon landing conspiracies, and assess whether I find a particular source trustworthy or not. These are straightforward prompts, and you can answer with almost anything, provided you can back it up with sources. For most classes these sources will be the ones you’ve already read, but some classes will also have a long research paper where you’re expected to do independent research. One unanticipated benefit to come out of the COVID-19 pandemic is that many universities and libraries digitized large sections of their catalog, so finding sources and doing research has never been more accessible. Finally, some classes will have formal midterms and finals, but these are usually straightforward. They typically take the form of a short paper written relatively quickly, a few paragraph questions, or very rarely the few dreaded multiple-choice questions.

This has two effects. It keeps you engaged in both the class and the subject, as you are provided the opportunity – and indeed expected – to form and share your own opinions; It also teaches you how to synthesize those ideas in the first place. Taking two different sources and using them to form your own, new opinion is one of the primary skills of historians. This is the bedrock of critical thinking and is becoming more and more valuable. In the digital age, where we are constantly bombarded with information and opinions, the ability to cut through the noise and try to find facts is essential to staying well informed.

Studying history also teaches fundamental research skills. It can be frustrating at times but getting your hands on a new text and interrogating it for fresh ideas is a deeply rewarding experience. For a personal example, when I was working on my thesis over the Texas Navy, I kept running into a problem where a lot of the diaries and accounts I was looking for were lost in 1881 when the Texas capitol burned down, taking with it many archives. I found fragments in other primary sources, and a few long quotes in secondary sources, but nothing complete. I struck gold when I was looking through a ship’s log one day in the archival reading room, when the content suddenly changed. The words flipped upside down and became a diary. I suddenly realized what I was holding. The Texas Navy was so broke towards the end of its existence that they could not afford a new log book when one ended, so the captain took one of his younger officer’s journals and used the blank pages as the new log book. When it was filed in the archives, whoever did the filing chose to list it as a log book and not as a diary. What I thought was dry positional and wind speed data had suddenly turned into a treasure trove of information. I’m not exaggerating when I say that was one of the most exhilarating moments of my college studies. And research is filled with little “gold mine” moments like these.

Finally, studying history teaches you the value of communicating your ideas. Being a history major involves a lot of writing and talking. It’s all well and good to have a new idea, but you have to be able to communicate it effectively for the idea to get out and spread. At UT and at every other school I’ve looked at, there’s at least one course specially designed to teach students how to research history, but more importantly how to communicate it. By going to college, no matter what your major, you’re going to become knowledgeable on some advanced topics. That’s the point of going, after all. Sooner or later, you’re going to have to tell people what you learned. Most majors will have some sort of communications class built in, such as engineering communication or business communication, but the great part about history is that most of our work has communication built-in from the beginning. This means that if you become a history major, you’ll have much more experience communicating your subject than your peers in other fields.

So that’s what being a history major looks like. It’s not memorizing names, dates, and events. It’s about assessing sources, forming your own opinions and communicating them effectively. In the next part of the series, I’m going to go over why you should consider becoming a history major and what opportunities studying history can provide.