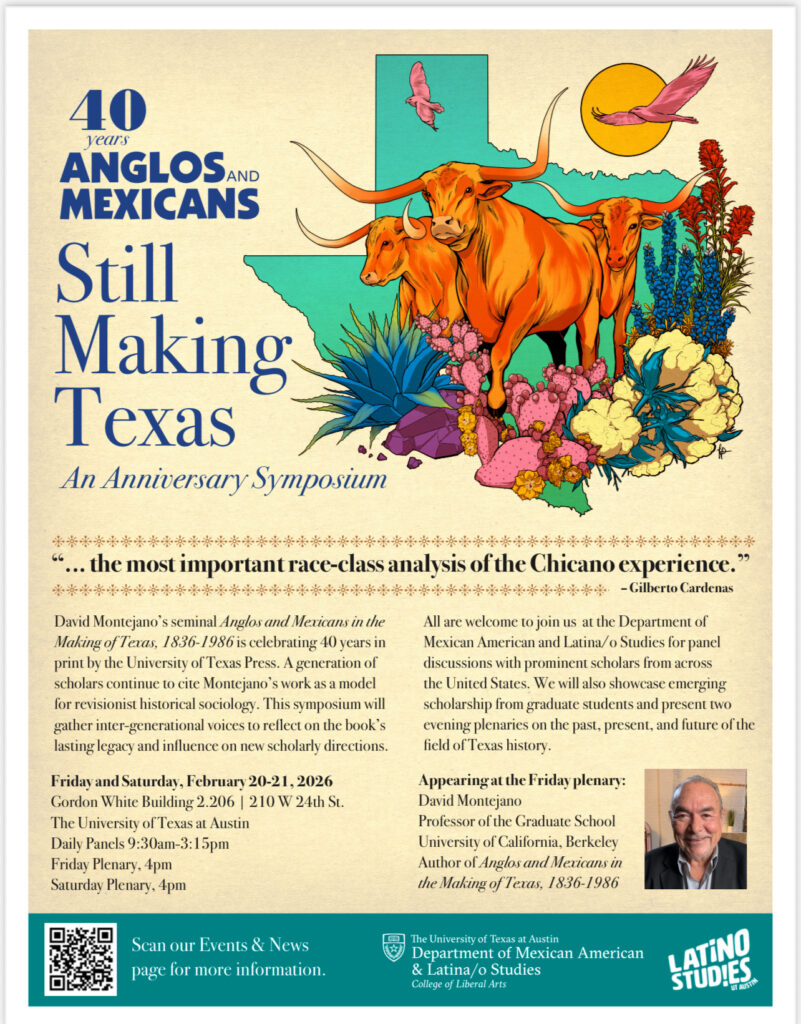

“Anglos and Mexicans; Still Making Texas” 40 Anniversary Symposium will take place on February 20-21, 2026 at the University of Texas at Austin. More details at the end of the article.

When I first read Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836-1986, it felt like I was reading about the entire world. My entire world. By that point, I had lived my entire life in the area under Montejano’s analysis. Some critics questioned Montejano’s methodological flexibility, yet for readers who grew up in that region, Anglos and Mexicans can explain everything. Unless you grew up wondering “Is Texas Bigger than the World-System?”, Anglos and Mexicans may not resonate as strongly. When I read Anglos and Mexicans, I hear strains of stories my grandfather told me about his father, the Hebbronville dairy farmer Robert McBryde. I see the mythologized King Ranch demystified. I remember stories my high school Ag teacher, Mr. Analiz, told me about how the palm tree and grapefruit came to Mission, brought by land speculators trying to entice Midwest Anglos to settle here. So, for me, readingAnglos and Mexicans represents the first time that evidence went deeper than the archive; it resonated from within. I knew that what was written was correct because I had lived it and heard decades of stories from those who had lived more of that history than I had.

My response to Anglos and Mexicans is precisely the kind of engagement Montejano’s work invites. For a work of history to generate that degree of emotional and intellectual resonance is no small achievement. That Montejano’s study can still produce such an effect in me and in others speaks to the enduring force of its analysis. Rarely does a work of scholarship offer such sustained insight into a vexing social problem. Rarer still is the study that does so in a way that reshapes an emerging field. First published in 1987, David Montejano’s Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836–1986 has proven to be one of those foundational works, setting the terms for subsequent scholarship on race, power, and political economy in Texas.

To quote Texas: An American History author Benjamin Johnson, “David Montejano was country before country was cool. Long before the explosion of scholarly interest in borderlands in the 2000s, he asked penetrating questions about how Mexican-descent people made Texas society in the 150 years after the Texas Revolution.” Despite early criticisms of Anglos and Mexicans’ “heavy reliance on secondary sources,” or the “perceptible parochial view” of its author, those same reviewers praised “the imaginative scholarship and impressive scope of Montejano’s work” and claimed that “within the context of Texas historiography, it will have great impact and may become a classic.”[1]

Granted, Anglos and Mexicans was not the first attempt at a systemic–structural account of race-relations in the Southwest. But it was among the first to advance such an analysis so forcefully and coherently. To paraphrase reviewer Mario T. Garcia, the book is a defining “contribution to the revisionist historiography of the Southwest and West.”[2]

Though rooted in Texas, Anglos and Mexicans is not simply a foundational text in Texas history. It is a seminal work of Southwestern history, Chicane studies, borderlands studies, and the analysis of racial capitalism in the United States. Montejano’s method—which combined archival research, sociological analysis, and political economy—established a model for the interdisciplinary work that defines Ethnic Studies today. Since Anglos and Mexicans’ publication in 1987, there have been many groundbreaking works of scholarship whose authors explicitly draw from or cite the book as a pivotal influence. The Injustice Never Leaves You by Monica Muñoz Martinez; From South Texas to the Nation by John Weber; White Scourge by Neil Foley; and Working Women into the Borderlands by Sonia Hernández—among many others—come immediately to mind. Whether subsequent scholars have extended his insights, challenged his framework, or attempted to move beyond it, Anglos and Mexicans set the terms of debate on race and class in the Southwest.

What has made this book so impactful? By Montejano’s own assessment, “cultural analysis was the dominant analysis” prior to UT Press’ publication of Anglos and Mexicans in 1987. Anglos and Mexicans rejected the prevailing conflict of Anglo–Mexican relations as differences in “culture…value orientation” that triggered a “cultural clash…and the result [being] segregation,” as previous (Anglo) scholars did.[3] No, what set the book apart upon publication was its argument that “the diversity of Mexican–Anglo relations…reflected the various ways in which ethnicity was interwoven into the class fabric of these two societies.”[4] While a visiting professor at UC–Berkeley, a chance placement one floor under the office of famed economist Paul S. Taylor gave Montejano the “window to the past” he needed to make such bold proclamations.[5] The result is a 150 year wide window into the Texas—Mexico border region’s transition from “pre-capitalist” or “semi-feudal” to “Modern;” in essence it opens into view the full process of Texas’ incorporation into the World System. In this sense, what happened between 1836 and 1986 in the Texas—Mexico border region was a local node in the centuries long, violent birth of the modern world. The dispossession of Mexican and Tejano land by Anglo settlers was not a repetition of the lord—serf contradiction that propelled European development over centuries, but instead a permutation in essence manifesting in alternate forms; a race—labor based social hierarchy.

Using the “gold mine” in Taylor’s 1920s–1930s interviews with Nueces County Anglos, Montejano interpreted the unspoken intent of early twentieth century Anglo ranchers and merchants to illuminate the dominant ideologies of turn-of-the-century South Texas.[6] Montejano used Taylor’s interviews—alongside census data, land records, news articles—to authoritatively argue that systems of racial domination in South Texas evolved through distinct periods of incorporation, reconstruction, segregation, and integration. Those interviews exposed how systems of racial domination are inseparable from labor exploitation and land dispossession. Perhaps most importantly, Anglos and Mexicans demonstrated the utility of Montejano’s signature “relaxed class–analysis,” one that introduces “race or ethnicity into the whole discussion.”[7] In doing so, Montejano staked a position that neither strict cultural analysis nor Marxist orthodoxy was sufficient to explain the complex interplay of race and class.

Mexican cowboys branding cattle. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The upcoming 40th anniversary of Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas offers a unique moment to assess the book’s generational impact. If some now consider the book dated, regionally limited, or overly traditional, that only sharpens the case for its reassessment. The strongest ideas can travel and adapt to new material conditions. Does Anglos and Mexicans’ insistence on the structural still offer a clever lens of analysis? What did—and does—Anglos and Mexicans mean to the three generations of scholars who have read and worked with it? What still resonates within its analysis? What remains insufficient or undertheorized? What has been left unresolved in the histories Anglos and Mexicans sought to narrate? How have Anglos and Mexicans continued to make Texas, 1986–2026? The Department of Mexican American and Latino/a Studies at UT Austin has organized “Anglos and Mexicans; Still Making Texas,” a symposium to address not only these questions but to imagine where the next forty years of Chicane, Borderlands, and Southwestern scholarship should be oriented. This symposium is more than a tribute. It is also an intervention and expansion.

Because the “Making of Texas” is a project without a finish line, we gather this February not merely to celebrate a forty-year-old text, but to stress-test its framework against the urgent realities of 2026. While Montejano’s 1987 edition laid the groundwork for understanding land dispossession and labor regimes, the decades since have introduced new complexities—from the expansion of the carceral state and mass deportations to a deeper scholarly reckoning with gender and Indigeneity. “Anglos and Mexicans; Still Making Texas” will take place February 20–21, 2026, at the Department of Mexican American and Latino/a Studies’ Gordon White Building. Across two days of panels, roundtables, and featured conversations, participants will return to Montejano’s central provocations: race and class as mutually constitutive social forces, uneven development as a regional condition, and “making Texas” as an ongoing political project. This symposium will be of interest not only to historians of Texas and the U.S.-Mexico borderlands but also to scholars, students, educators, and community members concerned with the long afterlives of land dispossession, labor regimes, racial formation, and state power in the Southwest.

The University of Texas at Austin, where Montejano studied, later taught for many years, and where his papers are now housed, will host the symposium as a homecoming celebrating his enduring contributions. Rooting this dialogue in the specific institutional memory of the Center for Mexican American Studies (CMAS) and MALS allows genealogical continuity while writing the future of Chicane and Latinx Studies. We invite scholars, students, educators, and community members to join us as we trace this intellectual genealogy and set its trajectory forward.

Ethen Pena is currently pursuing a PhD in Mexican American and Latino Studies at The University of Texas at Austin, with research centered on power dynamics, Anzaldúan theory, Radical Chicano Politics in the Southwest. He is dedicated to bridging academia and grassroots initiatives to inspire meaningful social change.

[1] David G. Gutierrez, “The Third Generation: Reflections on Recent Chicano Historiography: Mexicano Resistance in the Southwest. Robert Rosenbaum.; Let All of Them Take Heed: Mexican Americans and the Campaign for Educational Equality in Texas, 1910-1981 . Guadalupe San Miguel Jr.. ; Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836-1986. David Montejano. ; The Texas-Mexican Conjunto: History of a Working Class Music . Manuel Pena,” Mexican Studies 5, no. 2 (1989): 293; James E. Crisp, “Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836-1986,” The Journal of Southern History 55, no. 1 (1989): 143–44; Ellwyn R. Stoddard, “Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836-1986,” Contemporary Sociology (Washington) 17, no. 4 (1988): 475; Crisp, “Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836-1986,” 144.

[2] Mario T. Garcia, Review of Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836-1986, by David Montejano, The American Historical Review 94, no. 4 (1989): 1185.

[3] Montejano oral history, VOCES.

[4] David Montejano, Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836-1986, 1st ed. (University of Texas Press, 1987), 245.

[5] Montejano oral history, VOCES.

[6] Montejano oral history, VOCES.

[7] Ibid.