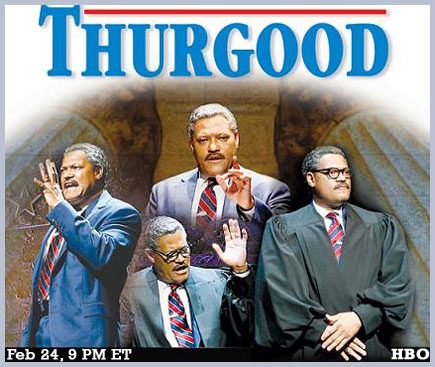

The new HBO Films production of George Stevens, Jr.’s one-man play, Thurgood, is a portrait of a man who knows and respects the power of the law as a force in American society.  Laurence Fishburne’s characterization of Marshall is multifaceted and gripping in its depiction of his warmth, humor and above all, determination, and while the biographical format offers only one point of view on the Civil Rights Movement, Thurgood’s is a likeable and authoritative one.

Laurence Fishburne’s characterization of Marshall is multifaceted and gripping in its depiction of his warmth, humor and above all, determination, and while the biographical format offers only one point of view on the Civil Rights Movement, Thurgood’s is a likeable and authoritative one.

Simply staged and filmed, Fishburne appears throughout the play alone on stage except for a wooden table, chairs, a pitcher of water, and a wall dressed with a white-on-white stucco American flag that serves as a projection screen. The performance and the sheer drama of the events of Marshall’s life—his personal experiences growing up in Baltimore with Jim Crow; arguing Brown v. Board before the Supreme Court, twice; speaking to LBJ in the Oval Office; confronting General MacArthur over the treatment of Black troops in Korea—do not need bells and whistles to make short and enjoyable work of the 105-minute running time.

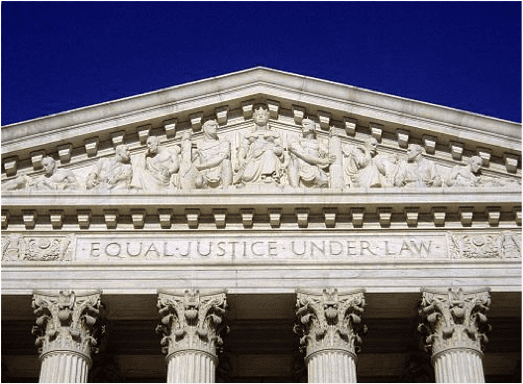

Throughout the film we hear in Marshall’s voice his mentor Charles Hamilton Houston’s motto: “The law is a weapon, if you know how to use it.” Marshall is certainly a master of martial strategy as we see him working against the clear-cut injustices of segregation, from his first big victory at the state level against the segregated University of Maryland, later affirmed nationally in Gaines v. Canada,through the 1954 Brown decision. Marshall is a man of the law, and we never see him question the wisdom or efficacy of his chosen strategy. This makes it difficult to maintain the drama in the second half of the film, when Marshall’s purpose and guiding principles are presented less clearly.

Marshall describes in a few lines of the monologue his frustration with Martin Luther King Jr.’s strategy of civil disobedience—a strategy which greatly taxed the resources of the NAACP’s legal defense fund—by recounting a imagined conversation where King relates the bona fides of civil disobedience by citing Thoreau. Marshall reminds King that Thoreau penned that essay “IN JAIL,” not after being sprung by a team of lawyers working overtime. While this moment offers both a laugh and some insight into Marshall’s role in the Civil Rights Movement beyond Brown, it misses an opportunity to explore the limitations of Marshall’s legal strategy. Once Marshall is appointed to the court, we hear that Richard Nixon was not among his fans and that Nixon’s enquiries after his health during a hospitalization were met directly with the words, “Not Yet!” Yet we hear little about the bussing decisions that inspired Marshall’s conflicts with the President.

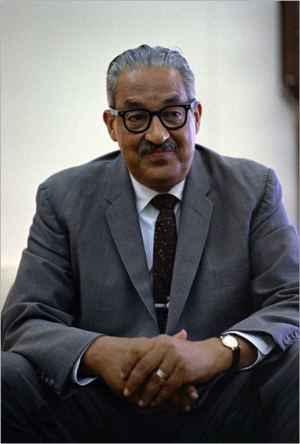

Perhaps this limited perspective is a necessary evil of biography. Marshall’s son, John, who spoke at a pre-screening Q&A at the Texas premiere of the film at the LBJ Library, suggested depths of Marshall’s thought about the role of law in society not displayed in the film by quoting his father speaking in 1992:

The legal system can force open doors and, sometimes even knock down walls. But it cannot build bridges. That job belongs to you and me. We can run from each other but we cannot escape each other. We will only attain freedom if we learn to appreciate what is different and muster the courage to discover what is fundamentally the same.

Watching the film with these words of Thurgood Marshall ringing in my head, I hoped to see more of Marshall the bridge builder, rather than a champion over segregation (however charming and human). Thurgood Marshall certainly was a champion, but he was not one to rest on his laurels, and while Stevens’ screenplay offers a moving portrait of a man, it could have more successfully captured the complexity of the world he lived in.