by Howard Miller

“WWJD?” A student of mine told me in the early 1990s that in her school the interrogating initials meant “Who Wants Jack Daniels?” Of course, most Americans today know that they mean “What Would Jesus Do?” The question has been ubiquitous in American popular culture for three decades. But few know that it was first asked in a novel. And even fewer know that the author’s working drafts of that novel can be seen today in the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

Reverend Charles M. Sheldon first asked “What would Jesus Do?” in an 1896 novel entitled In His Steps. Sheldon was an advocate for the Social Gospel, which sought to situate Jesus in his own culture and insisted that his life and teachings should guide the way Christians live their own lives in a very different culture.

Reverend Charles M. Sheldon first asked “What would Jesus Do?” in an 1896 novel entitled In His Steps. Sheldon was an advocate for the Social Gospel, which sought to situate Jesus in his own culture and insisted that his life and teachings should guide the way Christians live their own lives in a very different culture.

The novel is set in the fictional mid-western city of Raymond. It begins with the arrival of an out of work stranger, who, after a week of unsuccessfully seeking employment among church members, interrupts the Sunday service to ask the startled members what it meant for them to follow Jesus in their daily lives. And then he collapsed and died! In the Sunday evening service, the pastor challenged his congregation to answer the stranger’s question, to pledge that for a year, before making any major decision, they would first ask, “What Would Jesus Do?”

And the Christians of Raymond begin to transform their city. An opera singer vows to sing only at church. A newspaper becomes a Christian daily and loses many customers but is then subsidized by a convenient rich woman, who also builds a tenement for the poor. A rail superintendent resigns his position to protest the corruption of the railroad industry and then begins to crusade for economic reform. A college professor runs for public office in order to reform government along Christian lines. A merchant starts profit sharing with his employees. And all finally come to focus on the area of town called the Rectangle, a crime-ridden slum dominated by saloons and the unchurched men who control them.

All of the changes are gradual and paternalistic. None challenges the status quo of Raymond’s middle class, Protestant, capitalistic society. There will be no holding of all things in common. Sheldon specifically rules out any kind of socialist thorough reconstruction of society that would challenge the rights of private property. It is enough that those who have take care of those who do not have as much as they. Sheldon also makes it clear that no one should decide that Jesus wants him or her to give all that he or she has to the poor. There will be no Saint Francis of Raymond.

All of the changes also conform to traditional Victorian expectations of gender and sex roles. All the things that the women and men in the novel do to follow Jesus are within those traditional roles. The opera singer, as she performs, appeals to the heart, as women are intended to. And her singing converts people. Under her influence, a dissipated rich young man dedicates his life to reforming the idle rich young men who had been his friends in dissipation. Only when he has found his mission in life does he become resolute, disciplined, and purposeful. And only then does the woman he loves begin to find him attractive enough to marry him.

In His Steps was an instant best seller. In the twentieth century it sold more than thirty million volumes. But as that century developed, the novel ceased to be a major element in shaping Protestant culture in America, until, that is, the seventies and eighties. In those decades the novel’s central question, if not the book itself, became a favorite of the evangelical Christianity that became increasingly powerful in American culture.

In the mid eighties “WWJD?” began to appear on the wrists and necks of young Christian girls and women. Jesus became a fashion statement! And within a decade the question was everywhere in the marketplace of American consumer culture. By 2000 advertisers had accustomed Americans to ads based upon Sheldon’s question, as in “What Would Jesus Drive?”

And then George W. Bush identified himself and the Republican Party with Christianity in general and with Jesus in particular to an extent without precedent in American politics. The Republican Party became, in the first Bush Administration, as close as we have seen to a “Christian party in politics” in American history.

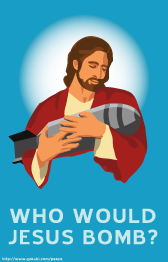

Then in the second Bush administration, that identification with Jesus became a problem. First, several Republican leaders who were outspoken defenders of traditional family values were involved in scandals involving homosexual activity. As Americans became ever more critical of Republican politicians whose actions were so at variance with their stated beliefs, they also grew more critical of the President’s actions, especially in the Middle East. Because the President proclaimed that Jesus was the model and guide for his life, critics, and especially cartoonists, could not resist using Sheldon’s question to criticize Mr. Bush. Cartoon after cartoon asked, inevitably, “Who Would Jesus Bomb?”

I don’t know what Charles Sheldon would think of George W. Bush and his party. I suspect that he would appreciate a president who said that Jesus was his favorite philosopher because “he changed my life;” who said that he took his orders from his heavenly father, not his earthly father; and who gave us what he called a “faith-based administration.”

But we can see the irony in the role that In His Steps played in the downfall of the “Christian Party in Politics.” Little did the Topeka pastor know in 1896 that his arresting question would become in the American marketplace in the early twenty-first century an advertising slogan that would help bring down a president and party he would probably have wholeheartedly supported.

Sheldon followed in the steps of Henry Ward Beecher, the most popular Protestant minister of the late Victorian period, and originally wrote his novel, chapter by chapter, as sermons to be delivered on Sunday evening before being finally published as a novel. Those chapters – and the pen he used! — can be seen at the Humanities Research Center at UT here in Austin.