By David Oshinsky

In 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court in Furman v. Georgia struck down state death penalty laws nationwide on grounds they violated the Eighth Amendment’s protection against “cruel and unusual punishment.” The 5-4 decision was extremely controversial. Each justice wrote a separate opinion; not one could be persuaded to join with another. The combined verbiage filled 232 pages, making Furman the wordiest decision the Court had ever released. And the implications were stunning. Not only were 587 men and two women immediately removed from death rows across the country and re-sentenced to life in prison, but capital punishment itself now seemed a relic of the past.

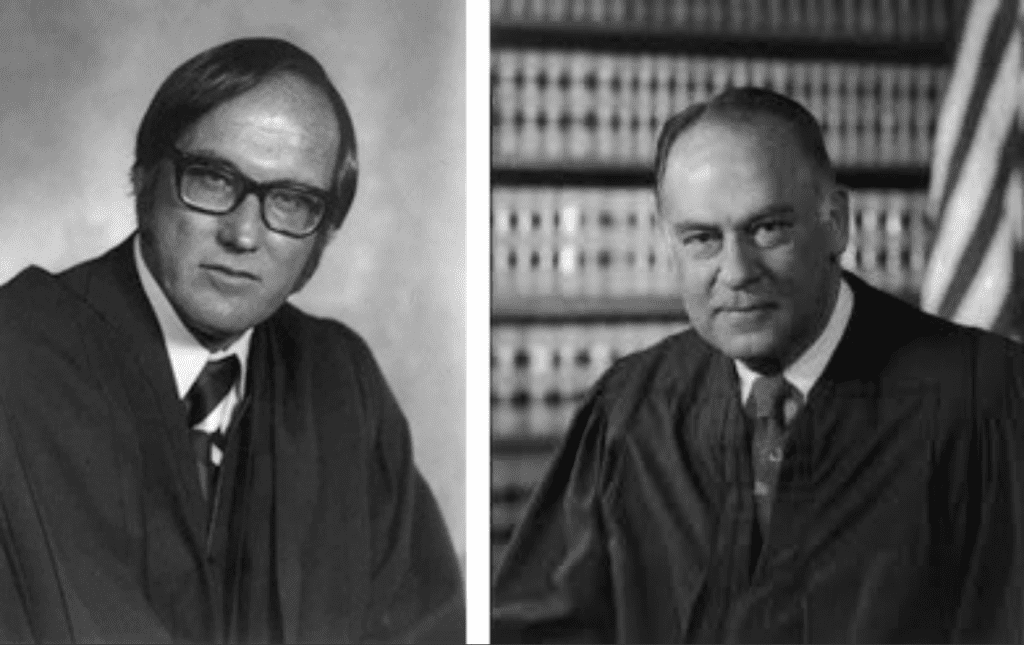

The Court’s liberal wing—William Brennan, William O. Douglas, and Thurgood Marshall—portrayed the death penalty as a barbaric punishment, employed almost exclusively against poor and minority defendants, which violated the nation’s evolving standards of decency. The more conservative justices—Nixon appointees Harry Blackmun, Warren Burger, Lewis Powell, and William Rehnquist—strongly disagreed. Each pursued a different line of argument, noting, for example, that capital punishment had been endorsed by the Founding Fathers, that it enjoyed wide support among the American people, and that it was meant to be decided in the state legislatures, not by nine unelected men in Washington. That left the two centrist justices—Potter Stewart and Byron White—to determine the outcome.

Both men believed the death penalty to be morally and legally defensible, yet both were troubled by its use. The issue wasn’t prejudice or evolving standards or original intent, they argued; it was the arbitrary and capricious method in which the punishment had been applied. The death penalty was cruel and unusual, said Stewart, “in the same way that being struck by lightning is cruel and unusual. . . . The Eighth Amendment cannot tolerate the infliction of a death sentence . . . so wantonly and freakishly imposed.”

Stewart had a point. Every year, more than 20,000 Americans are murdered. Of those arrested for these crimes, about half make a plea bargain or are found guilty at trial. Only a few hundred actually receive the death penalty, many of whom are then spared upon appeal. Such a system—about 100 executions for every 20,000 murders—raises obvious doubts about the effectiveness of deterrence and retribution. More important, it leads one to ask: Who, exactly, is chosen to die? Can we honestly say that the few defendants we execute have committed more horrible crimes than the thousands of defendants who receive prison terms? And if not, is it possible to create the kind of guidelines that will sort out the truly deserving offenders?

Furman had left the door slightly ajar. By deciding that capital punishment as currently practiced was unconstitutional, the justices had implicitly invited the individual states to rewrite their death penalty statutes in a manner that did not violate the Eighth Amendment. But no one on the Court expected this to occur. As Chief Justice Burger remarked privately to friends, “There will never be another execution in this country.” So, what happened?

Quite a lot, it turned out. In Capital Punishment on Trial, I look at the social and political landscape of the 1970s—the rise in urban crime, the cries for “law and order,” popular culture’s embrace of vigilante action, from “Death Wish” to “Dirty Harry.” In short order, the removal of the death penalty by “bleeding-heart judges” became part of the angry debate over why America’s streets had become more unsafe, and what could be done to fix the problem. Politicians promised a tougher stand on crime, leading numerous state legislatures to rewrite their death penalty statutes—the key new provisions being a bifurcated trial with a separate punishment phase in which “aggravating” and mitigating” circumstances could be weighed; and a clearer definition of what constituted a capital crime.

In 1976, the Supreme Court in Gregg v. Georgia upheld the new death penalty statutes in Florida, Georgia, and Texas, ruling that they provided capital juries with sufficient guidance and discretion. Other states quickly followed suit. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court moved cautiously on the death penalty, carefully narrowing its scope while avoiding the issue of abolition—ruling, for example, that those under eighteen and the mentally retarded cannot be executed, nor can those convicted of crimes, such as rape in which a life is not taken. No issue over the years has been more difficult or contentious for the individual justices than this one. And no issue has demanded more of their time.

Today, as in the past, Americans support capital punishment in overwhelming numbers, according to public opinion polls, despite a stream of reports that portray the system as racially biased, weighted against the poor, expensive to maintain, and prone to wrongful convictions. The issue strikes so powerfully because of the combustible elements it contains—elements of morality and justice, on the one hand, punishment and vengeance, on the other. The future of capital punishment is difficult to predict, especially in the post-9/11 world. At the moment, however, one thing is clear. For a majority of Americans, some crimes are simply too heinous to be punished by anything less than death.

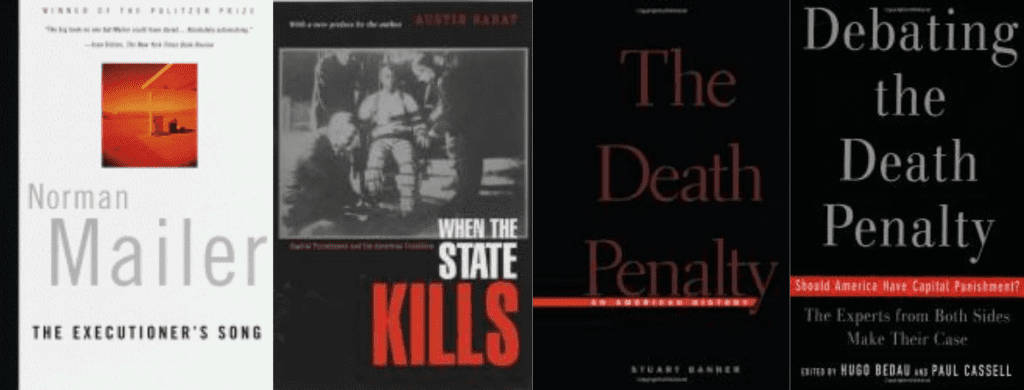

Stuart Banner, The Death Penalty: An American History, (2003).

Serious students of the death penalty must begin here. Law Professor Stuart Banner provides an engaging, richly detailed and superbly objective history, examining both the law and the popular culture surrounding capital punishment, and showing why Americans, almost alone in the developed world, still endorse the practice.

Austin Sarat, When The State Kills: Capital Punishment And The American Condition, (2001).

Political scientist Austin Sarat is an unabashed opponent of the death penalty, and one of the most articulate voices for its abolition. Capital punishment, he believes, is an extra-ordinarily divisive issue, triggered by our worst human instincts, such as racism and vengeance. Both supporters and opponents of the death penalty will find much to chew on.

Hugo Bedau and Paul Cassell, Debating The Death Penalty, (2004).

This superb collection of essays covers both sides of the debate. Hugh Bedau, a longtime opponent of the death penalty, offers his perspective, as do other abolitionists; but what makes this collection unique is the articulate defense of capital punishment delivered by the likes of Paul Cassell, Louis Pojman, and Judge Alex Kozinski. Rarely have so many ideas regarding the death penalty been covered with such skill and sophistication.

Norman Mailer, The Executioner’s Song, (1979).

Mailer won the Pulitzer Prize in fiction for his magisterial account of the life and execution of Gary Gilmore, a convicted murderer who demanded to die. The book is far more than fiction, of course, blending dozens of interviews and true details into an epic account of one’s man descent into barbarism— and the cultural realities of American life that Mailer believes led Gilmore down that path.

You may also enjoy:

Timeline: Death Penalty in the US

The Supreme Court

Photo Credits:

Supreme Court Justices Rehnquist and Potter