Shores of Knowledge has gotten its share of uncritical, rave reviews from Bill Moyers to the Washington Post. I wrote the following review for a small academic, European journal, Centaurus. There it will be read only by a handful of specialists, if I’m lucky. I want to make this review available to a wider public in Not Even Past in the hopes of engaging a general conversation about aspects of the book that I find troubling and that most likely will go unmentioned in most reviews. We need a raucous discussion about our shared notions of progress and modernity. And we need to ask: who got to be curious?

Shores of Knowledge has gotten its share of uncritical, rave reviews from Bill Moyers to the Washington Post. I wrote the following review for a small academic, European journal, Centaurus. There it will be read only by a handful of specialists, if I’m lucky. I want to make this review available to a wider public in Not Even Past in the hopes of engaging a general conversation about aspects of the book that I find troubling and that most likely will go unmentioned in most reviews. We need a raucous discussion about our shared notions of progress and modernity. And we need to ask: who got to be curious?

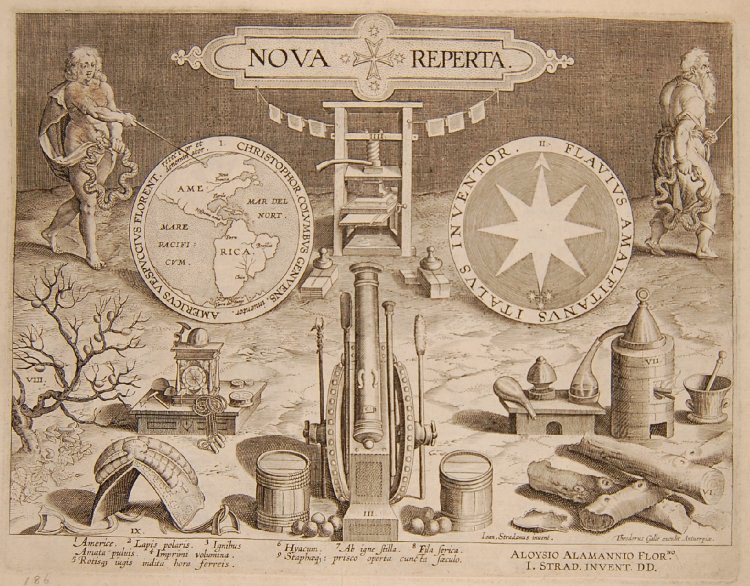

The ancient Greeks were curious. Superstitious folks in the Middle Ages were not. The Renaissance untethered curiosity from the clutches of theology. Curious men then turned their attention onto America and other newly found lands to bring about modern science. This is the argument of Joyce Appleby’s Shores of Knowledge. Appleby, a distinguished historian and a former president of the American Historical Association, manages to turn an incredibly messy story, and even messier historiographies, into a neat, yet extremely old-fashioned narrative. In the 1590s the Flemish engraver and painter at the service of the Medici, Jan van der Straet (Stradanus), produced a series of prints, Nova Reperta (New discoveries), that could have summarized the spirit animating Shores of Knowledge : curious explorers, like Christopher Columbus, with the help of new technologies (compass, gunpowder, and printing press), opened up a continent, America, so rich in new creatures and natural products, to transform knowledge about the world forever.

Appleby begins with Columbus and ends with Alexander von Humboldt and Charles Darwin. In between these bookends a host of figures, all male, come in for entertaining vignettes: sixteenth-century Spanish conquistadors cum naturalists-ethnographers; Renaissance editors of travel accounts; amateur sixteenth- and seventeenth-century curiosity collectors and naturalists; early eighteenth-century emerging experts and specialists on insects, plants and ethnography; mid eighteenth-century state- sponsored French astronomer-academicians measuring the earth; late eighteenth-century British and French naval naturalists and ethnographers cataloguing the islands and peoples of the Pacific. To assemble her book, Appleby relies exclusively on English editions of authors whose works remain mostly untranslated from Latin, Italian, Spanish and French, and Nahuatl, including figures like Columbus, Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo, Bartolomé de las Casas, Antonio Pigafetta, Peter Martyr, Giovanni Ramusio, Richard Hakluyt, Theodor de Bry, Ulisse Aldrovandi, Francis Bacon, Robert Boyle, Carl Linnaeus, comte de Buffon, Charles Marie de la Condamine, Pierre Louis Maupertuis, Louis Antoine de Bougainville, James Cook, Humboldt, Darwin, and a host of other minor figures.

This is not a book of original scholarship but of popularization, and it shows. Take for example the case of the alleged lack of medieval ‘curiosity’ in understanding nature. Historians of medieval natural philosophy would take issue with Appleby’s bold, sweeping assertions: Medieval Franciscan nominalists, for instance, transformed the Muslim science of optics and created a bold new discipline. The geometry they developed to interpret the behavior of light rays, in turn, was the foundation upon which Galileo and Newton mathematized uniform and uniformly accelerated motion. Medieval scholastic alchemical practices and theories of matter laid the ground for the empiricism of Boyle and Newton. In short, the Middle Ages were not the Dark Ages that Petrarch, Voltaire, and, now, Appleby suggest.

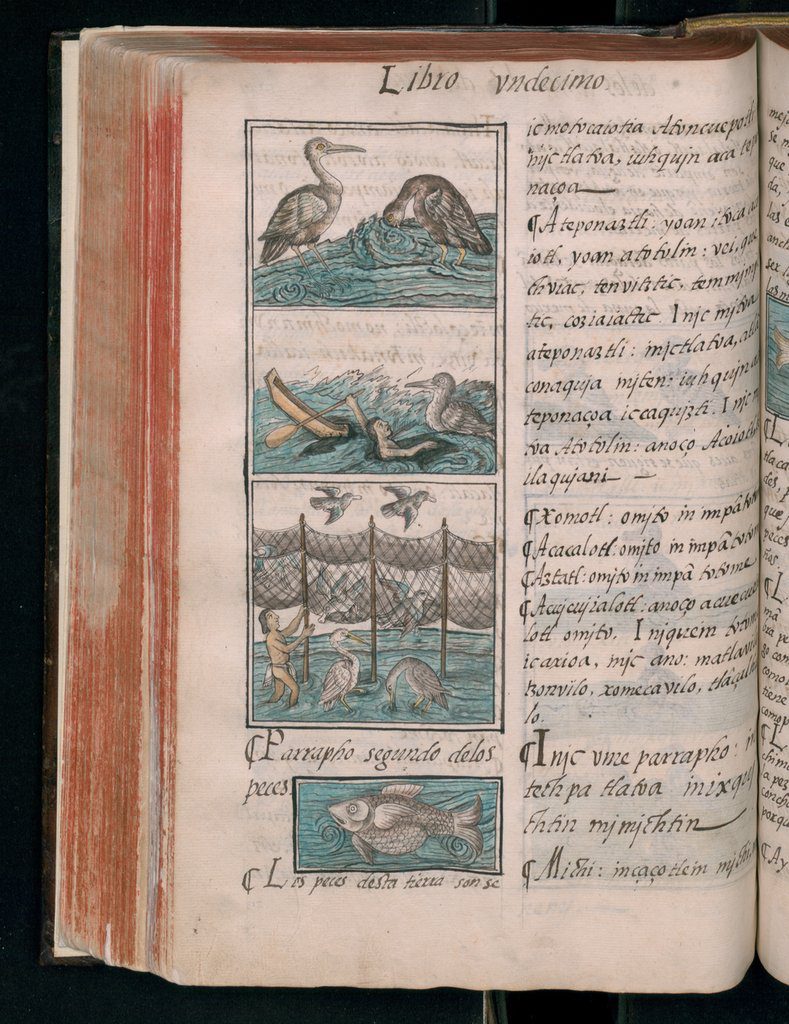

Although Appleby seeks to give intellectuals of the Spanish Monarchy their due, the way she goes about doing it reflects centuries of accumulated historiographical biases and leaves out decades of recent historiographical correctives. Amidst bouts of barbarism and superstition, a few curious Spanish conquistadors and missionaries make cameo appearances in chapter one; then, they disappear. Appleby deals with the usual suspects: Oviedo, Las Casas, Hernandez and Bernardino de Sahagún.

Bernardino de Sahagún, and others, “Florentine Codex, On birds and fish,” Book 11. Natural History (Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, Italy)

The role of Spanish and Spanish American naturalists in La Condamine’s expedition is limited to a sentence or two. José Celestino Mutis appears in the chapters on Linnaeus and Humboldt in a couple of paragraphs only to suggest that his late-eighteenth-century collecting efforts went to waste due to the neglect of ignorant bureaucrats.

“Justicia,” a naturalist document from the Mutis Expedition. (Real Jardín Botánico CSIC. Madrid. DIV. III A-1679)

Humboldt, the hero, appears traversing countless Spanish American kingdoms, gathering long-neglected statistics from the obscurity of offices and libraries, and, in the process, illuminating locals, including Bolivar, on the potential of political and economic freedom they had not yet grasped.

We know from Maria Portuondo’s Secret Science: Spanish Cosmography and the New World (2009), for example, that the modernity Appleby attributes to seventeenth- and eighteenth-century France and England was fully possible in sixteenth-century global Spain without the need of the printing press. Portuondo demonstrates that cosmographic works (including Copernicus’s) circulated widely in manuscripts among students in academies and universities and among secretive bureaucracies on both sides of the Atlantic. The absence of a public, created by the circulation of scientific materials in print, did not stop the development of the things Appleby associates with modernity: the full mathematizing of the world; the development of the Baconian category of fact; the pragmatic embrace of the idea of moving earth to make sense of tides and calculate longitudes; the development of countless machines and astronomic techniques to map out longitude. The case of La Condamine is even more jarring because Appleby cites Neil Safier’s Measuring the New World (2008) throughout. Safier’s argument is that La Condamine was not the naturalist hero Appleby puts forward but an entrepreneur of self-promotion. Much of La Condamine’s work was not empiricist collecting by a daring philosophical traveler. It was plagiarism and recycling of the work of others, including Jesuits and local creole scholars. That La Condamine today could still pull off his act of self-aggrandizement before Appleby’s eyes speaks volumes about the endurance of imperial, geopolitical misleading distribution of epistemological authority.

How Appleby deals with Humboldt is equally striking. Humboldt was not the first to correlate the earth’s climates onto vertical mountain heights. It was Jose de Acosta, whose extraordinarily influential sixteenth-century natural history Appleby completely ignores.

In fact, I have argued in print that Humboldt’s remarkable output, including his 30 volumes on the New World, ought to be read as a synthesis of the Spanish American Enlightenment, not the product of a genius working in isolation. Humboldt himself acknowledged that he was the beneficiary of the most generous eighteenth-century, state-sponsored policies of natural history collection in Europe as a whole: some 60 “Spanish” expeditions to the Americas and the Pacific. Appleby mentions every European state-sponsored scientific expedition into the Pacific but completely ignores the largest: Alejandro Malaspina’s, which happened to be “Spanish.”

My problem with the book does not stop with the interpretations. There are countless errors of fact throughout. The following is just a selection: The second and third parts of Oviedo’s Historia were not published in 1535 (33); Martyr Decadas were eight, not nine (78); it wasn’t the Mexican Revolution that brought the trade of the Manila Galleon to an end (186); the places Humboldt visited were not called Columbia (sic) and Ecuador (218); La Condamine did not ‘trail blaze through the Orinoco River basin’ (219); and so on.

Shores of Knowledge is an old-fashioned hagiographic treatment of knowledge as a liberating force. Like Petrarch and Voltaire, Appleby argues that travels of discovery in the age of imperial global expansion set us free from the clutches of medieval superstition. Decades of scholarship on empire, power, slavery, plantations and the geopolitics of epistemological authority as constitutive of early modern natural philosophy and natural history evaporate.

Appleby’s review ultimately points to the potential and limits of popularization. How should historians reach wider audiences? My issue with her book is not with her style. Entertaining histories, vignettes, and anecdotes are helpful in illustrating complex issues of analysis and theory and Appleby uses them to great effect. My problem is that her strategies suggest that, for a book to be popular, historians ought to reinforce narratives the public expects. In her case these include such common tropes as medieval obscurantism, the power of America’s discovery in producing miraculous epistemological transformations, and the enlightened, heroic tale of “European” male naturalists triggering modernity juxtaposed to the one of cruel Spaniards, poignant yet marginal. Unfortunately those popular narratives are often little more than collections of shibboleths and stereotypes. How to craft historical narratives that are widely read but that at the same time rattle the public into jettisoning their historical parochialism? That is the historians’ true dilemma.

And don’t miss Jorge Cañizares Esguerra’s review of Our America: A Hispanic History of the United States