A variety of books skewering myths about science and scientists.

by Alberto Martinéz

Ronald L. Numbers, ed., Galileo Goes to Jail, and Other Myths about Science and Religion (2009). Twenty-five historians write twenty-five brief but incisive chapters debunking famous myths mostly about Christianity and the sciences. It addresses well known claims, such as the assertion that the medieval Christian Church suppressed the growth of science, that medieval Christians taught that the Earth was flat, that Copernicanism demoted humans from the center of the universe, and that Darwin reconverted to Christianity on his deathbed.

Ronald L. Numbers, ed., Galileo Goes to Jail, and Other Myths about Science and Religion (2009). Twenty-five historians write twenty-five brief but incisive chapters debunking famous myths mostly about Christianity and the sciences. It addresses well known claims, such as the assertion that the medieval Christian Church suppressed the growth of science, that medieval Christians taught that the Earth was flat, that Copernicanism demoted humans from the center of the universe, and that Darwin reconverted to Christianity on his deathbed.

John Waller, Einstein’s Luck: The Truth About Some of the Greatest Scientific Discoveries (2004). Historian John Waller thoughtfully writes about various heroes in the history of science, to debunk famous claims about their discoveries. His examples are mostly from the history of the lifesciences, including discussions on Darwin, Louis Pasteur, Joseph Lister, Alexander Fleming, and others. For example, Waller rehearses historian Robert Olby’s arguments that Gregor Mendel did not really discover the laws of heredity. Thus this is essentially a popular book, as Waller relies mostly on accounts by other historians, and therefore, some of its claims have eroded. For example, it follows a famous article in arguing that eclipse expeditions of 1919 hardly confirmed Einstein’s theory of gravity, that the data was misrepresented in favor of Einstein, but actually, more recent and very thorough historical analysis by Daniel Kennefick has shown that the observations really were analyzed fairly in 1919.

John Waller, Einstein’s Luck: The Truth About Some of the Greatest Scientific Discoveries (2004). Historian John Waller thoughtfully writes about various heroes in the history of science, to debunk famous claims about their discoveries. His examples are mostly from the history of the lifesciences, including discussions on Darwin, Louis Pasteur, Joseph Lister, Alexander Fleming, and others. For example, Waller rehearses historian Robert Olby’s arguments that Gregor Mendel did not really discover the laws of heredity. Thus this is essentially a popular book, as Waller relies mostly on accounts by other historians, and therefore, some of its claims have eroded. For example, it follows a famous article in arguing that eclipse expeditions of 1919 hardly confirmed Einstein’s theory of gravity, that the data was misrepresented in favor of Einstein, but actually, more recent and very thorough historical analysis by Daniel Kennefick has shown that the observations really were analyzed fairly in 1919.

Tony Rothman, Everything is Relative, and Other Fables from Science and Technology (2003). Physicist Tony Rothman writes nineteen sections discussing a broad variety of topics, some of which involve myths in science. This popular book is well written and very engaging, though it lacks enough use of primary sources and therefore it echoes stories by writers that one might assume to be reliable but which have some defects, for example, it too highlights the false myth about Einstein and the eclipse of 1919. Nevertheless, Rothman’s book is insightful and worthwhile, including lively discussions about discoveries and inventions such as telephones, light bulbs, and penicillin. For Rothman’s excellent account of the myth that the young mathematician Évariste Galois feverishly formulated group theory on the night before he died in a pistol duel, see Rothman, Science à la Mode: Physical Fashions and Fictions (1989).

Tony Rothman, Everything is Relative, and Other Fables from Science and Technology (2003). Physicist Tony Rothman writes nineteen sections discussing a broad variety of topics, some of which involve myths in science. This popular book is well written and very engaging, though it lacks enough use of primary sources and therefore it echoes stories by writers that one might assume to be reliable but which have some defects, for example, it too highlights the false myth about Einstein and the eclipse of 1919. Nevertheless, Rothman’s book is insightful and worthwhile, including lively discussions about discoveries and inventions such as telephones, light bulbs, and penicillin. For Rothman’s excellent account of the myth that the young mathematician Évariste Galois feverishly formulated group theory on the night before he died in a pistol duel, see Rothman, Science à la Mode: Physical Fashions and Fictions (1989).

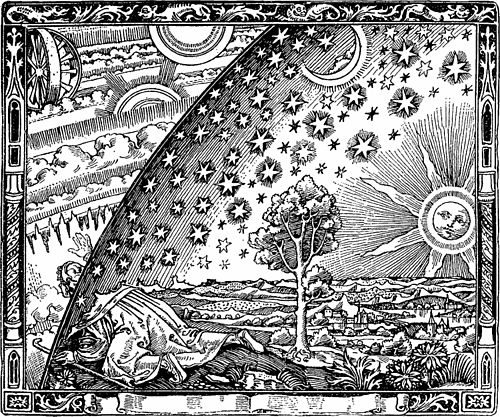

An engraving depicting the nineteenth-century idea about medieval beliefs that the world is flat. The Flammarion engraving is a wood engraving by an unknown artist that first appeared in Camille Flammarion‘s L’atmosphère: météorologie populaire (1888). The image depicts a man crawling under the edge of the sky, depicted as if it were a solid hemisphere, to look at the mysterious Empyrean beyond. The caption translates to “A medieval missionary tells that he has found the point where heaven and Earth meet…”