By Joan Neuberger

On January 1, 1900, an editorial in the New York World predicted that the twentieth century would “meet and overcome all perils and prove to be the best that this steadily improving planet has ever seen.” The war that broke out just a few years later in 1914 showed that the twentieth century would become something entirely different.

By 1900, most European countries had constitutions, elected representative governments, and limits on monarchical power. Increasing control over nature with industrial machines and modern capitalism offered many Europeans and Americans an unprecedented degree of material comfort and prosperity. With that came a growing sense of their individual achievement, as well as the technology and prosperity to assert their national power in new ways over other people at home and in colonies abroad. But the Europeans’ use of modern power to dominate, educate, classify, and economically exploit others created new conflicts over culture, identity, sovereignty, security, even over different ideas about the basic components of human nature. These conflicts, beginning with colonial liberation struggles and especially the First World War would call into question the very foundations of European power and Europeans’ faith in progress and in the genuine achievements of the entire previous century.

There was considerable enthusiasm for a war in the summer of 1914. Serious disagreements beset every country in Europe: conflicts over political rights, human rights, economic developments, and colonial and other policies. Many people believed that a short war would somehow “wipe the slate clean,” and allow material progress and prosperity to continue. And everywhere people believed that the deep cultural and economic connections among European nations would prevent war from continuing for more than a few months. Nineteenth-century wars in Europe had been of limited scope and duration due to visionary international agreements made in Vienna in 1814-15 after the defeat of Napoleon. Europeans thought they had become too “civilized” to fight a drawn-out, destructive conflict.

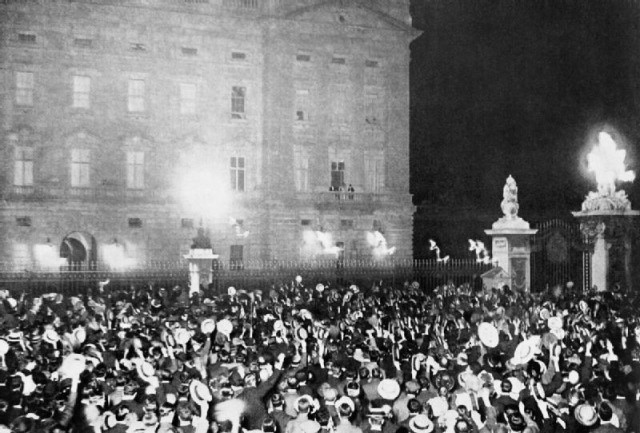

The declaration of the war brought crowds of people to the streets of every capital city in Europe to celebrate. Friedrich Meinecke, later a major German historian, described the outbreak of the war as “one of the great moments of my life, which suddenly filled my soul with the deepest confidence in our people and the profoundest joy.” In many countries, even workers, who had been locked in battle with their governments, hastened to join the middle-and upper-classes in the support of the war.

There were, however, other voices. Peasants, who would make up the bulk of the war’s cannon fodder, were indifferent to the political conflicts that divided European nations and resented the draft. And a few prescient diplomats recognized the folly their leaders were embarking upon. Maurice Paléologue, the French ambassador to Russia, wrote in his diary: “So the die is cast . . . The part played by reason in the government of peoples is so small that it has taken merely a week to let loose universal madness.”

It would take only a few weeks for the truth of the Russian peasant saying to be apparent to all: “It is a wide road that leads to war and only a narrow path that leads home again.”

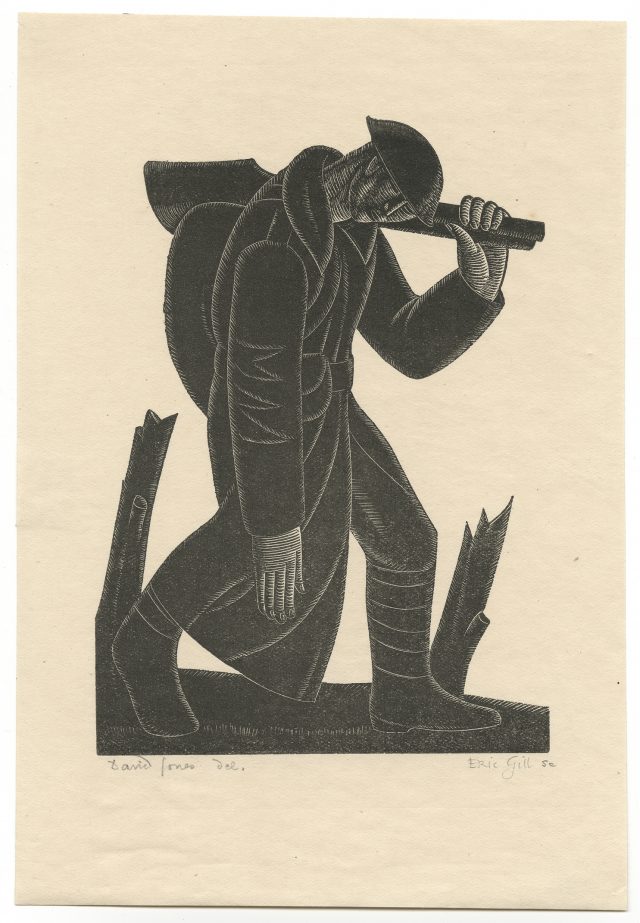

The documents, posters, letters, and photographs currently on display at the Harry Ransom Center illustrate the way ordinary people on the home front and the battlefront experienced the narrowing of that road.

More events, sponsored by the Harry Ransom Center

Please join us for a symposium on World War 1 sponsored by the Institute for Historical Studies at UT Austin:

Remembering World War 1 on its Centennial,” April 16, 2014. 3:30-5:30. GAR 4.100. Free & open to the public.

All images courtesy of Harry Ransom Center unless otherwise indicated.

Sources:

W. Bruce Lincoln, Passage Through Armageddon (1986)

Robin Winks and Joan Neuberger, Europe and the Making of Modernity (2005)