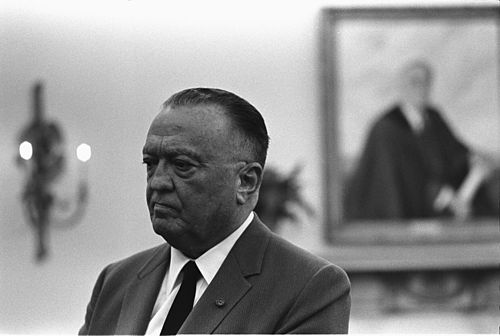

Academy Award-winning director Clint Eastwood presents a biopic of one of the most powerful and controversial figures of twentieth-century America in the film J. Edgar. Acclaimed actor Leonardo DiCaprio brilliantly portrays John Edgar Hoover, the first director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Eastwood and DiCaprio depict Hoover as a complicated individual, dedicated to modernizing crime investigation in the United States yet consumed with a desire for power, respect, and adoration. Hoover’s insecurities lead him to legal and ethical abuses of his authority, which cause great problems in both his personal life and professional legacy.

J. Edgar begins in the early 1960s, as an aging Hoover reflects upon his life to young agents writing a history of the FBI. Hoover grew up in Washington, D.C., the favored son of a domineering mother who continuously predicts that he will bring greatness to the family name. Such familial pressures cause Hoover to perpetually seek his mother’s approval throughout his life. While working in the Department of Justice following World War I, he catches the attention of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer and plays a key role in the notorious Red Scare, hunting down and deporting individuals suspected of Bolshevist sympathies. Hoover’s experience with the Palmer Raids converts him into a strident anticommunist.

Following his successes during the Red Scare, Hoover becomes director of the Bureau of Investigation (which would become the FBI in the 1930s). Hoover immediately sets out to professionalize his agency. He only hires individuals of excellent physical stature who commit to complete loyalty to the Bureau above any other persons or goals in their lives. His organization practices the most advanced crime-fighting techniques, as Hoover rigorously studies the new sciences of fingerprinting and forensics. During these years, two critical people enter Hoover’s life, Helen Gandy and Clyde Tolson. Miss Gandy, as Hoover calls her, chooses to forego romantic relationships in order to dedicate herself totally to her work. Impressed by such conviction, Hoover hires her as his personal secretary. He also feels an instant connection with Clyde Tolson, a young law school graduate, whom he names as his right-hand man.

Hoover perceives leading the FBI as the vehicle to achieve glory for both himself and his family name. He also truly believes his agency serves as the watchdog for his beloved country’s safety. The film recalls many famous historical events. Hoover’s FBI investigates the kidnapping and murder of renowned aviator Charles Lindbergh’s baby, contentiously finding only one suspect in the crime. Agents battle organized crime, and bank robbers, like John Dillinger. Hoover himself markets the organization, supporting efforts to lionize his “G-Men” in both comic books and movies, often exaggerating his own personal role in suspenseful accounts of arrests.

Yet Hoover’s obsession with empowering his beloved FBI causes him serious problems and raises ethical questions. His fear of losing the directorship and anxiety about domestic subversives leads him, with the help of Miss Gandy, to create a secret file with salacious information about some of the most powerful people in America. In a reoccurring scene, the FBI leader meets with new presidents entering the White House and asserts his authority though barely veiled blackmail. In a flashback, a young Hoover visits President Franklin D. Roosevelt, inquiring about how to handle information he has obtained detailing First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt’s intimacy with another woman. Understanding Hoover’s purpose, FDR gives the Bureau even more autonomy.

Thirty years later, Robert F. Kennedy and Hoover engage in a tense meeting, where the new attorney general attempts to reassert the Department of Justice’s authority over the FBI. Hoover makes clear that he possesses files detailing President John F. Kennedy’s extramarital affairs, and is not afraid to make this information public. A disgusted Robert Kennedy acquiesces to Hoover’s demands, fearful of a scandal that could embarrass his brother. In another infamous episode, the FBI director bugs Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s hotel room, collects evidence of the civil rights leader’s marital infidelities, and unsuccessfully attempts to blackmail him to prevent King from accepting the Nobel Peace Prize.

Hoover’s weaknesses also cause conflict in his own personal life. Though doted upon by his mother, he seems incapable of ever fulfilling her high expectations. When the body of the abducted Lindbergh infant is found, Hoover’s mother chastises him for failing to save the child and condemns him as possessing blood on his hands. The FBI director struggles with romantic relationships. The film presents him as awkward around women, but illustrates the deep bond he develops with Clyde Tolson, long rumored to be Hoover’s lover. However, even with Tolson, Hoover often demonstrates cruelty and chooses solitude. Because of his mother’s harsh warning to avoid homosexual relationships, Hoover withholds affection from the ever loyal Tolson, whom he clearly loves. Likewise, when Tolson and Miss Gandy express concern regarding Hoover’s obsession with destroying Dr. King, the FBI director ruthlessly berates them for questioning his judgment.

At the film’s conclusion, Hoover remains concerned with the future of the FBI and his own legacy. Following a meeting with Richard Nixon, the FBI leader expresses alarm to Miss Gandy and Tolson about the new president’s lust for power. Eastwood presents Nixon as even more sinister and paranoid than Hoover. At his request, Miss Gandy promises Hoover that she will always protect his secret files, and thus the integrity of both the FBI and himself. Sure enough, when Hoover passes away a few years later, President Nixon, while publicly praising Hoover, vulgarly orders his aides to confiscate the secret FBI files. When Nixon’s men search through Hoover’s office, however, they only find empty file cabinets. The film then ends showing Miss Gandy privately shredding a mountain of documents. The credits note that only a few misfiled papers from Hoover’s collection were ever found. Even in death, J. Edgar Hoover once again asserts his power over a sitting American president.

J. Edgar omits several critical historical episodes. Eastwood does not address Hoover and the FBI’s role during World War II. Surprisingly, the film barely mentions the Second Red Scare and McCarthyism, surely a seminal period in the time of Hoover’s FBI directorship. Also, we see scant attention to the larger civil rights movement beyond Dr. King. What about the FBI’s surveillance of organizations like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Black Panthers? Furthermore, how about FBI monitoring of antiwar groups during the Vietnam era? Certainly, a director can only cover so many stories in a movie, but these are important events, too.

Despite this minor criticism, Eastwood tells us much about the past that certainly is applicable today. The film’s central theme is power, and how its abuse can be very dangerous. Hoover’s lust for power causes him to breach legal and ethical boundaries, raising issues that continue to remain divisive among Americans. We live in a time when leaders, often in the name of national security, much like Hoover, utilize their powers with questionable methods. Much controversy surrounds the Patriot Act and electronic surveillance, supported by both Republican and Democratic administrations. Civil liberties in the age of terrorism, as in the Cold War era, again seem at risk. Hoover’s paranoia about subversives appears eerily similar to former Vice President Dick Cheney’s obsession with capturing suspected Islamic militants. What does it mean if, in our dedication to protect the United States, we violate the moral codes our country holds most dear?

J. Edgar is an excellent presentation of an individual and an organization which had profound, and controversial, influences upon American life in the twentieth century. Recalling many historical episodes with dazzling acting and fascinating storylines, viewers will find J. Edgar both intellectually stimulating and movingly entertaining.

Photo Credits

Uncredited photographer for Los Angeles Daily News, J. Edgar Hoover and his assistant Clyde Tolson, c 1939.

Abbie Rowe, John F. Kennedy, J. Edgar Hoover, Robert F. Kennedy, Oval Office, 1961

Yoichi. R. Okamoto, J. Edgar Hoover in the Oval Office, 1967