Congratulations, you passed your comps!

Now the reality sets in that in order to write your brilliant dissertation, you have to do some serious research. Here are a few things to remember in order to survive and even thrive during your research year.

1. Plan your stay around the archives’ hours and opening days (which do not always correspond with semesters).

Don’t organize your research trip around your school’s academic calendar. Before you even buy a plane ticket, check the schedule of each archive you want to visit. Use this to plan how long you will spend at each location. Some archives close for entire weeks, even months, around the winter holidays. Others close on certain days of the week, or have rules about ordering documents in advance. Most importantly, be sure that the archives are still operational. One of my colleagues arrived in Romania only to find that the archive she had hoped to visit was closed for the next three years for renovation.

2. Keep a consistent schedule but take breaks.

Establish a routine early on in your stay. The most important thing is to find the schedule that works best for you and stick to it. The first few adrenaline-fueled weeks go by in a flash, but by week four you’re exhausted. While maximizing your hours, remember to take plenty of breaks. Research has shown that people are more productive when they take consistent breaks every ninety minutes or so. Some of these breaks should be small, five to ten minute strolls down to the coffee machine, but one of these breaks should be substantial — at least thirty minutes. A good time to eat lunch or a snack. By breaking up your work like this, you are not only staving off hunger and malaise, but you are also giving yourself the time to process the information you have looked at so far. Give yourself breaks on the weekends and in the evenings as well. Determine when you will organize your research and write, but give yourself enough time to relax as well.

3. Determine what type of a relationship you will keep with your adviser and committee before you leave.

It is very important to discuss with both your advisor and members of your committee how often they would like to hear from you and in what capacity. Determining this before you leave will make your life much easier and will lay out clear expectations for you (and for your advisor!) Don’t be afraid to reach out to your advisor and members of your committee for advice when you run into difficult situations or when you need to celebrate a success. There’s a good chance that your advisor actually wants to hear from you.

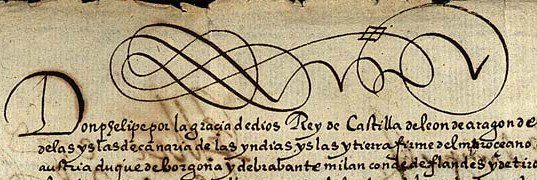

4. The archives’ inventories you have spent the past several months pouring over may be out of date or inaccurate.

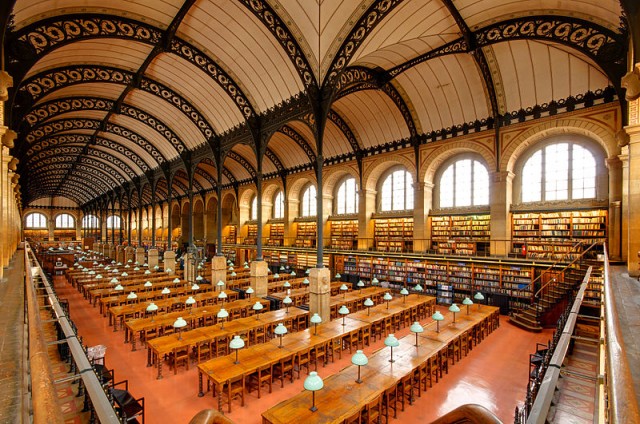

On my first day of research in Paris, I went to the archive that I thought housed the “treasure trove” for my dissertation. Ten minutes after confidently writing the call numbers on the reservation slips, the archivist returned saying tersely, “These documents do not exist.” It turns out that the online inventories were from the nineteenth century and did not conform to the new catalogue. It took me well over a full week to track down all the new call numbers, but many of the documents were still missing. This frustrating experience reminded me of something my comprehensive exam committee told me: Your dissertation proposal should serve as a blueprint and should be a constantly evolving plan. In other words, do not panic if the documents you thought would be in the archive are not there or are in a state of disrepair. Be flexible and creative in finding other sources and avenues of research and be prepared to modify your dissertation proposal accordingly.

5. Reach out to other scholars who have worked on similar projects.

Now that you’re an expert in your field thanks to comps, chances are you know who works on projects similar to yours. Don’t be afraid to contact your favorite historians for advice or help. Many of these historians will be delighted to hear from you and willing to share their experiences. One professor I contacted offered invaluable advice in regards to the archives and my argument.

6. Find a community of fellow graduate students, scholars, or expats to avoid the isolation that comes with research.

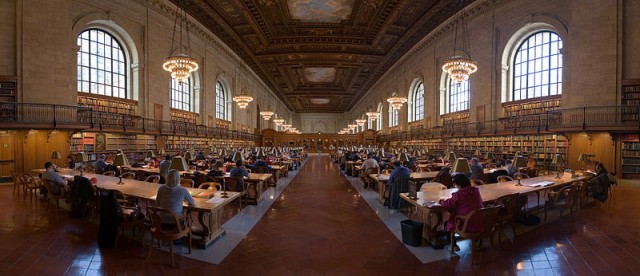

When I got to Paris, I met regularly with the other graduate students working in my archives. We discussed archival issues, research, and life in general. I also made sure to get coffee or lunch with different researchers. If you can, strike up a conversation with a fellow researchers in the coatroom or by the coffee machine, but if you’re a little bit shy you can send out an email to one of the many academic (H-Net for instance) listservs to see if there are other people working at your archives or in the same city who might be interested in meeting for coffee, a meal, or doing some sight seeing on the weekend. You can also meet people in cultural centers and clubs in your area. I joined the American Club of Lyon as well as the American Library of Paris where I got to go to a variety of events and meet expats from all walks of life. Other graduate students joined church choirs or audited classes at French universities. Some grad students chose to live in French dormitories in order to meet other French and international students. Even if you thoroughly enjoy the alone time that research provides, it is important to have some social interaction and a support community, otherwise you may find yourself having imaginary conversations with the authors of your documents.

7. Bring enough of anything from home that you deem a “necessity.”

This one seems like a no-brainer, but really examine what you feel you cannot survive without. If it is a favorite coffee, bring enough. If it is a certain pair of sweatpants, bring them. Depending on where you conduct your research, you can get away with bringing less because you can purchase comparable goods there. However, there are some things — medicine, contacts, glasses, and technological devices — that you should bring enough of to sustain you for your entire time abroad. Also remember that if you are traveling outside the US, your appliances may not work (and can even blow an electrical fuse in your apartment!). Bring adaptors.

8. You may finish earlier or later than you expected. Budget accordingly.

It is possible that those documents you thought held the “keys” to your dissertation weren’t really the magical artifacts you had hoped they were. You may notice that you’re going through documents at an alarmingly fast rate. Conversely, you may notice that you’re moving incredibly slowly. If you find yourself running out of documents to look at, start writing – or at least organizing your research. More than likely you’ll find gaps or related questions that didn’t initially occur to you to investigate. If you find yourself taking longer to complete your research, prioritize your documents and set realistic goals for yourself. Don’t assume that you’ll be able to immediately come back for the documents that you weren’t able to read. If all else fails, during the last week of your research, take pictures of all the documents you might need. You can always organize and read them at home.

9. Back up your work in multiple locations. Seriously.

Cameras break, memory cards go missing, computers crash, and external hard drives mysteriously start smoking. Back up your notes and photos in multiple locations. I backed up my photos and notes in three locations – on a cloud server, an external hard drive, and on memory cards. These notes and photos are your livelihood so remember to back them up every day. I made it a habit to immediately back up my memory cards when I got home both onto the external hard drive and to the cloud. I’d highly suggest buying high capacity (32GB) memory cards – this way you can just continue to take pictures all day without having to download them to your computer and delete the images.

10. Keep a research journal.

My research journal is full of half-developed ideas, embarrassingly wrong presumptions, and the occasional funny letter to myself (“Dear Future Julia”), however my research journal has proved indispensible to my dissertation. I kept a list of all the documents I examined, official notes, and a research journal. Everyone organizes their notes differently, but the Table of Contents feature in Microsoft Word was a quick and easy way to organize my official notes and I’d highly recommend using it. My research journal was much more unstructured. Whenever I was in the archive and noticed similarities between different documents or had a stroke of brilliance, I immediately wrote it into my research journal. After coming home from the archives each night, I also made a short entry, detailing my findings, any ideas I had, and what I planned to do the next day. Many of the ideas, similarities, or strokes of genius I had in my journal have grown into larger arguments or anecdotes for my dissertation.

Your research year will be full of both exciting finds as well as periods of somewhat monotonous searching. However, if remember to thrive instead of just survive your research year, it can be one of the most rewarding experiences of your academic career.

Julia M Gossard is a PhD Candidate in the History Department at UT Austin. During the 2012-2013 academic year, she conducted research in France thanks to a Department Fellowship, The Society for French Historical Studies Marjorie M. and Lancelot L. Farrar Memorial Award, and the American Society of Eighteenth-Century Scholars Robert R. Palmer Research Travel Award.