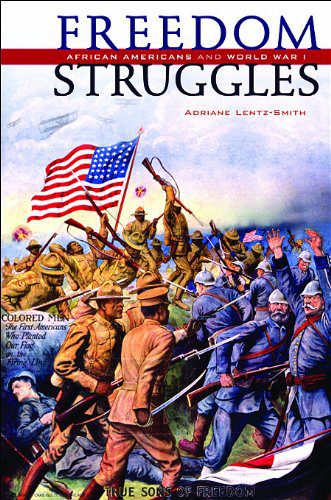

Moviegoers who recently flocked to cinemas around the country to take in George Lucas’ World War II aviation blockbuster, Red Tails, may be unaware of the long and checkered history of black servicemen in the American military in the decades before the ascendance of the now famous Tuskegee Airmen. Two recent books, however, provide well-documented accounts of the struggles endured by black soldiers as they fought for democracy on both sides of the Atlantic during and after World War I. Adriane Lentz-Smith’s Freedom Struggles: African Americans and World War I (2009) and Chad L. Williams’s Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era (2010) share in celebrating the triumphs of black soldiers during World War I as well as in exposing the profound hardships endured by these brave men.

Together, both books also offer a rich counter-narrative to traditional World War I history. By eschewing the classic topics associated with the subject, namely German nationalism and the heroism of white American soldiers and politicians, Lentz-Smith and Williams write the black soldier out of the margins and recount the wartime experience largely from his perspective.

Together, both books also offer a rich counter-narrative to traditional World War I history. By eschewing the classic topics associated with the subject, namely German nationalism and the heroism of white American soldiers and politicians, Lentz-Smith and Williams write the black soldier out of the margins and recount the wartime experience largely from his perspective.

Lentz-Smith’s Freedom Struggles spotlights the more than 200,000 black soldiers dispatched to Europe with the American Expeditionary Forces during the Great War and chronicles the numerous battles these soldiers encountered along enemy lines. Lentz-Smith reveals that sometimes white American soldiers were more threatening to black soldiers than the foreign enemies. Nonetheless, for many of these black servicemen, it was their sustained contact with Europeans, mainly French civilians, and especially French women and colonial African troops that helped shape their vision of an America unburdened by the racist impositions of Jim Crow. Through highlighting moments when French civilians graciously welcomed black soldiers into their war-torn nation and often shielded them from the indignities hurled from their fellow American soldiers, Lentz-Smith masterfully juxtaposes that foreign hospitable treatment with the more antagonistic racial climate that lingered back in the United States. Unfortunately, these sable heroes did not garner the same level of respect from their military counterparts or from the various American communities where segregation and a strict racial caste system governed social and political relations of the day. But Lentz-Smith points out that black servicemen were unprepared to surrender defeat either in Europe or at home in the States. Instead, they consistently demanded equality, recognition, and respect at nearly every turn.

Lentz-Smith’s Freedom Struggles spotlights the more than 200,000 black soldiers dispatched to Europe with the American Expeditionary Forces during the Great War and chronicles the numerous battles these soldiers encountered along enemy lines. Lentz-Smith reveals that sometimes white American soldiers were more threatening to black soldiers than the foreign enemies. Nonetheless, for many of these black servicemen, it was their sustained contact with Europeans, mainly French civilians, and especially French women and colonial African troops that helped shape their vision of an America unburdened by the racist impositions of Jim Crow. Through highlighting moments when French civilians graciously welcomed black soldiers into their war-torn nation and often shielded them from the indignities hurled from their fellow American soldiers, Lentz-Smith masterfully juxtaposes that foreign hospitable treatment with the more antagonistic racial climate that lingered back in the United States. Unfortunately, these sable heroes did not garner the same level of respect from their military counterparts or from the various American communities where segregation and a strict racial caste system governed social and political relations of the day. But Lentz-Smith points out that black servicemen were unprepared to surrender defeat either in Europe or at home in the States. Instead, they consistently demanded equality, recognition, and respect at nearly every turn.

In one particularly telling moment, Lentz-Smith recasts the infamous 1917 Houston Race Riot, also known as the Camp Logan Massacre, to illuminate how internecine military racial tensions coalesced with prevailing southern racial, gender, and class assumptions, resulting in a bloody uprising in which four soldiers and sixteen civilians perished. In the end, the riot that stemmed from the Houston Police’s racist and un-gentlemanly treatment of a black woman in a poorer part of the city, led to one of the largest military court martials in U.S. history. That members of the Twenty-Fourth U.S. Infantry ultimately came to this Houston woman’s aid and found themselves eventually hanging from government nooses or imprisoned for life, underscores Lentz-Smith’s main contention that black World War I soldiers valiantly fought on numerous fronts to help dismantle Jim Crow, push for recognition of their manhood, and certainly propel the modern civil rights movement, all while maintaining firm belief in President Wilson’s claim that the Great War was a “war for democracy.”

Torchbearers for Democracy, reiterates some of the major themes found in Freedom Struggles. Williams, like Lentz-Smith, probes black soldiers’ beliefs that military service would lead to a quicker acknowledgment of their citizenship and manhood rights. After all, military service has long been a vehicle for white men to prove their loyalty and fitness for American citizenship, so in the minds of many of black soldiers, the same formula had to work for them. Yet, Williams maintains that a bulk of the black soldier’s work would have to be performed at home since it was here that Jim Crow proved an unrelenting combatant. Williams offers a poignant chapter on how black veterans navigated the intensely violent summer of 1919, known as “Red Summer.” He also reveals the numerous ways in which black soldiers and veterans fought to end racial inequality in practically every area of American life—from politics to labor. Williams also reflects on the role of black soldier in history and memory, ultimately arriving at some original and insightful claims regarding the notions of internationalism and diaspora.

Torchbearers for Democracy, reiterates some of the major themes found in Freedom Struggles. Williams, like Lentz-Smith, probes black soldiers’ beliefs that military service would lead to a quicker acknowledgment of their citizenship and manhood rights. After all, military service has long been a vehicle for white men to prove their loyalty and fitness for American citizenship, so in the minds of many of black soldiers, the same formula had to work for them. Yet, Williams maintains that a bulk of the black soldier’s work would have to be performed at home since it was here that Jim Crow proved an unrelenting combatant. Williams offers a poignant chapter on how black veterans navigated the intensely violent summer of 1919, known as “Red Summer.” He also reveals the numerous ways in which black soldiers and veterans fought to end racial inequality in practically every area of American life—from politics to labor. Williams also reflects on the role of black soldier in history and memory, ultimately arriving at some original and insightful claims regarding the notions of internationalism and diaspora.

Overall, Williams’ study offers a more thorough engagement of the Great War as a defining moment in the long quest for civil rights in America. Taken together, these two books provide a much needed historical context, or the prequel, to George Lucas’s astounding World War II fighting drama, Red Tails. Those interested in understanding the foundations of black military service and the pre-1950s Civil Rights Movement should certainly consult both monographs and the movie.

For more on African American soldiers in WWI:

“Teaching with Documents” from the National Archives

Photo Credits:

New York’s famous 369th Regiment returning from France

National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the War Department, Record Group 165, ARC Identifier: 533548