David Lean’s magisterial film epic, Lawrence of Arabia (1962) gave us a mythic hero struggling against impossible odds. The film’s theatrical merits—breathtaking cinematography, nuanced performances, riveting score—cemented Western audiences’ enduring interest in the title character, but offered little factual substance about the life of a compelling and controversial historical figure, and supported a lopsided view of the 20th century Middle East. The film best serves as a gateway to understanding the real Lawrence and the legacy of British Colonialism in a still-tumultuous region.

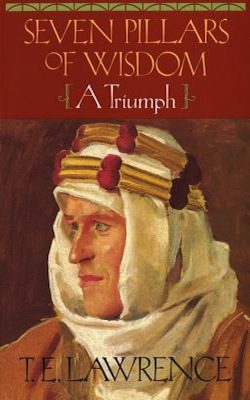

If the nearly four-hour movie is an introduction, T.E. Lawrence’s own memoir, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, is a 600-page next step. Lawrence aficionados bear the badge of completing the windswept tome with great pride: the author records labyrinthine tribal relationships and the minutiae of desert battles in its densely detailed pages to many readers’ great exhaustion. Yet Seven Pillars continues to capture the imagination of readers interested in Britain and the Middle East during World War I with its arresting poetry. Some might initially balk at the book’s bulk, but by the time Lawrence describes a night of feasting under the stars with Auda ibu Tayi and the Howeitat Bedouins, the spell has been cast. Yet, however seductive his prose and the great sweep of his narrative, Lawrence’s autobiography remains unbalanced. Lawrence himself admits a degree of unreliability. “All men dream: but not equally,” he writes, “Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their mind wake in the day to find that it was vanity: but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act their dream with open eyes.” As a dreamer of the day, Lawrence’s account of his own life falls far short of objectivity. His tendency to flicker between excess and asceticism foreshadows the ferocity of the historical and moral debate about his role—and Britain’s—in the Arab Revolt.

Lawrence was an eccentric, divisive figure during his life, and he remains divisive more than eighty years after his death. In July of 1915, the British High Commissioner in Egypt, Sir Henry McMahon, initiated a correspondence with Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, on the subject of lands under Ottoman administration. McMahon and his counterparts in London saw growing Arab nationalism within the Ottoman empire as a potentially useful wartime tool. Cultivating Arab national aspirations would undermine Ottoman sovereignty, particularly desirable for Britain at the beginning of World War I. The McMahon-Hussein correspondence suggested to the Sharif that Britain would support an Arab kingdom under the Sharif’s suzerainty, carved out from Ottoman lands—including Jerusalem and the Holy Lands. Many scholars point to the correspondence as impetus for the Revolt, and something Lawrence vocally encouraged. When the later Sykes-Picot Agreement and the Balfour Letter came to light, indicating British colonial aspirations and promises to create a Jewish homeland in the same parcel of land, McMahon’s commitments to Arab self-rule suddenly rang hollow. The question of how much Lawrence knew about McMahon’s apparent duplicity—and of course the subject of Arab or Israeli control of the area—remains bitterly contentious.

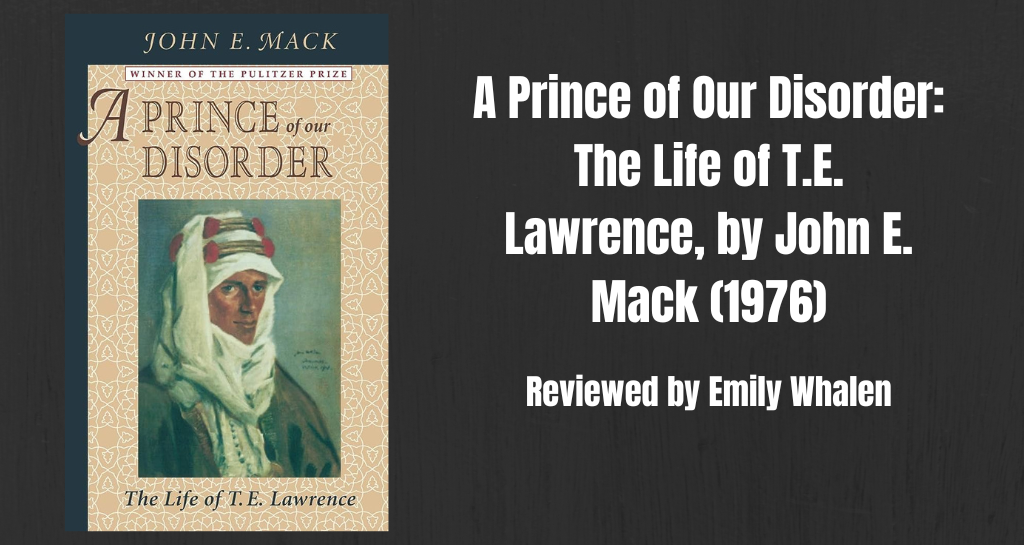

Those seeking a more balanced assessment of Lawrence would do well to turn to a third source: John Mack’s psychological biography of Lawrence, A Prince of Our Disorder. Mack’s Pulitzer Prize winning volume sharpens the reality of Lawrence as an individual in history and thus casts a clearer distinction between man and myth. For example, in Seven Pillars, the Damascus Campaign of 1916-1918 quietly blooms into an eternity; Mack neatly folds those desert months back into the context of Lawrence’s life, devoting roughly 50 out of 600 pages to the same two years. A historicized and humanized Lawrence distills for the reader the extraordinary leadership qualities and the fortuitous convergence of circumstance that enabled him to crest, alongside his guerillas, the wave of the Arab Revolt. The mythological Lawrence, now discernible in contrast, tells the reader much about the way that wave broke, contextualizing both the subsequent criticism and adulation of Lawrence. Mack’s work stands as a sensitive, fully contextualized portrait of an historical figure, with family secrets, literary predilections, and intensely emotional qualities that both malformed him and made him “of a higher quality.” A Prince of Our Disorder grounds and enriches Seven Pillars and Lawrence of Arabia. It reminds the reader of Lawrence’s limitations.

“The wash of that wave,” writes Lawrence of the Arab Revolt, “…will provide the matter of the following wave, when in the fullness of time the sea shall be raised once more.” Lawrence’s continuing attraction lies in what Mack describes as the man’s tendency to offer “his extraordinary abilities, his essential self, and even his conflicts to others for them to use according to their own need.” The present conflicts of the Middle East can appear hopelessly intractable, with many countries locked in bloody conflict or bound to an unjust status quo. Moments of change are moments of hope. So Lawrence survives, as we watch for another wave.

Mack, John E. A Prince of Our Disorder: The Life of T.E. Lawrence (Boston: Little, Brown, 1976).

Lawrence, T. E. Seven Pillars of Wisdom: A Triumph (London: Penguin, Doubleday, 1925).