Beginning with the title and continuing through the final pages, James C. Scott’s Against the Grain seeks to subvert the historical narrative of inevitable progress toward civilization that has been dominant for millennia. Instead of framing agriculture as a driver of enlightened civilization, he conceives of it as a social and ecological building block that spawned early states that were more coercive than civil. Scott may not have launched the first attack of this kind, but his clear prose synthesizes evidence from a broad range of disciplines to craft a well-reasoned barrage of arguments, causing irreparable damage to a foundational element of western thought – that, since the first agricultural civilizations, the organized state has brought about enlightened and morally superior society.

Beginning from the perspective of a “thin” Anthropocene, a historical approach that emphasizes the ways in which human action has shaped the environment and landscapes, Scott emphasizes the richness of social-ecological relations before organized states appeared. The more traditional “thick” Anthropocene claims the environmental impact of modern industry has so thoroughly transformed the planet that it constitutes a new geological epoch. The “thin” perspective points out that that human activity, especially ecosystem niche creations through fire, so pervaded the landscape that it is difficult to think of ancient nature as separate from human influence.

Early settled communities built around the diverse and abundant sustenance activities along rivers and wetlands slowly domesticated plants and animals millennia before states first emerged. These novel arrangements, which Scott terms the “late Neolithic multi-species resettlement camps,” constituted the core of a long, slow transition. Contrasting with the more abrupt “Neolithic Revolution,” such a transition yielded not only plants with bigger seeds and more docile animals, but also dangerous new organisms that thrived in larger communities – diseases. Only through the combination of elevated birthrates and inherited immunity in settled communities could states eventually coagulate. But in many ways, these states represented, to borrow a phrase from Chief Seattle’s 1854 speech, “the end of living and the beginning of survival.”

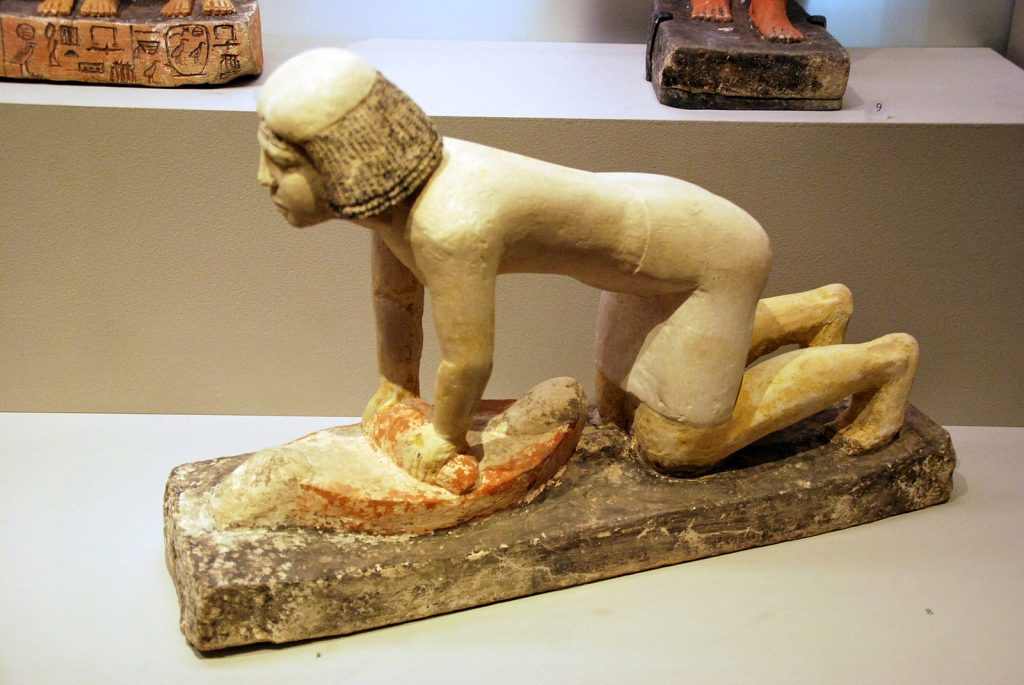

Scott primarily defines states through the presence of tax collection, officials, and walls, with grain serving as the keystone to the political-economic system. Predictable, transportable, and calorie-dense, grain represented a surplus that could be monitored, collected, and, crucially, controlled. Put another way, grain was the perfect resource for taxation, allowing for the emergence of a ruling class. Despite the advantages yielded by such a surplus – a large, non-agricultural workforce – grain-derived civilization remained fragile. A single bad harvest could throw an early state into disarray, and even without catastrophic floods or drought, extractive agricultural and forestry practices often led to a slower demise. When combined with this ecological instability, the laborious nature of agrarian life made it so unappealing that early states likely built walls for restriction as much as for protection.

An Ancient Egyptian Statue of Grinding Grain (via Wikimedia)

Early states had to overcome tremendous social and ecological friction, so much that they typically were short lived. Only through the control and acquisition of its primary resource – people – could early states persist. The incorporation of human assets, whether by conquest of small neighboring communities or through slave trade, invigorated early states. Such a capricious system lacks robustness, and state failure could come from without or within. Such narratives of “collapse,” as it has often been framed, should be viewed critically. Scott argues what may appear to an archeologist as the catastrophic downfall of a monumental capitol may be more accurately, though not exclusively, thought of as disassembly into decentralized, independent communities. It is crucial to keep in mind that, perhaps as late as 1600, non-state peoples constituted the vast majority of global human population. States were “small alluvial archipelagos,” surrounded by hordes of ungoverned people who provided valuable trading and military allies, at least when they weren’t raiding and pillaging.

By incorporating innovative forms of evidence, Scott illuminates a critical perspective on the origins of modern states. He should have pointed out the difficulties of life outside states to create a more balanced narrative, but this omission takes little away from the central argument. Crucially, Scott compels the reader to be cognizant of the invisible or illegible, both historically and in our present lives. To make his argument, Scott relies on historical sources, such as dental analysis of ancient teeth, that prove just as informative as formal edicts or other, more visible historical sources. In a time with so much information, Against the Grain reminds us to be critical of whose story is told and why. For this reason, Scott’s work should have a place in courses focused on both the present and the future, not just the past. It suggests that students ask about the role coercion and bondage play in the twenty first century, or if our economy is built around appropriation or ecological wisdom. The reader, while learning about the distant past, cannot help but ponder what about our daily lives we take for granted and which narratives or stories should be elevated, and which should be relegated to the past.

Steven Richter is currently a PhD Student in the Community and Regional Planning program in the University of Texas School of Architecture whose focus is on sustainability, regional land use, and natural capital.

You May Also Like:

A Primer for Teaching Environmental History

Crimes Against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, Thieves, and the Hidden History of American Conservation

Banana Cultures: Agriculture, Consumption & Environmental Change in Honduras and the United States