By Ann Merkle

How do we remember? When asked, “Where were you when President John F. Kennedy was shot?” those who lived through that momentous time recall it vividly and often emotionally, even though they may not have been in Dallas on that fateful day. For those too young to remember first-hand, movies or documentaries may inform their impressions. As we approach the 50th anniversary of JFK’s tragic assassination on November 22, 1963 and the days that followed, the Blanton Museum of Art offers yet another lens through which to view this dark chapter in American history – two paintings by American artist Peter Dean (1934-1993), Dallas Chaos (1981) and Dallas Chaos II (1982). In them, Dean composes a rewrite of history in his own expressive language, challenging collective memory and forcing viewers to reconsider what they may have previously accepted as fact.

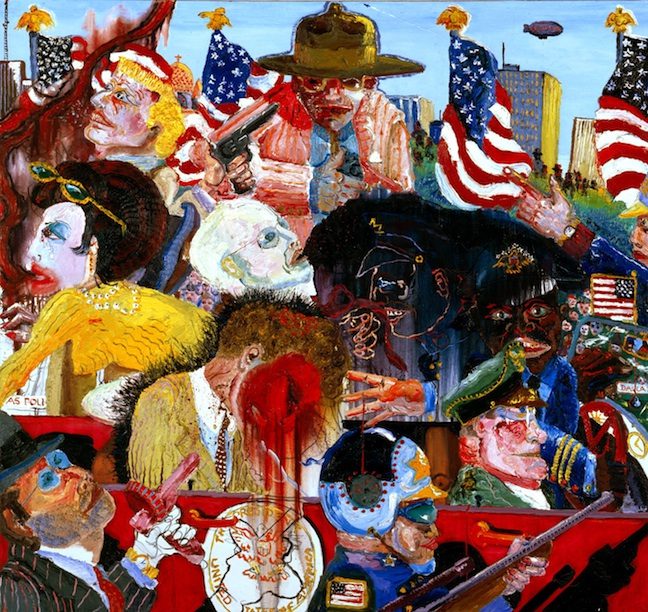

Dallas Chaos presents the instant of President Kennedy’s assassination in a claustrophobic yet dynamic scene. A flurry of policemen, Secret Servicemen, military members, and others swirl around JFK’s central figure, his head drooping towards his lap, splattered with blood. It’s initially a struggle for the viewer to identify who is who amidst the sea of patriotic imagery, with American flags fluttering in the wind and in the hands of onlookers. Individual motives in the painting become increasingly confusing – are the police protecting, or are they threatening the president? The viewer is left to wonder who is good and who is evil, or if there is a distinction to be made at all.

In the companion painting, Dallas Chaos II, Dean confronts his audience with similar imagery, this time focused on the murder of JFK’s presumed killer, Lee Harvey Oswald. Unlike JFK’s assassination, the event presented here is an act of violence that many Americans witnessed in real time on live television. The majority of figures wear disguises, with Oswald in a jester’s motley garment, fierce dogs with the heads of pigs, one policeman in a Klansman hood, and another resembling a Nazi. Members of the media clamor to record the scene with their cameras and video recorders as a gangster-like Jack Ruby swoops in and fires the fatal shot. In response, Oswald contorts, a cascade of masks tumbling down from his face. In this confusing narrative, it is once again nearly impossible to differentiate between heroes and villains.

Why are works such as these significant for us now, fifty years after JFK’s assassination? Dean once said, “The murder of John Kennedy was the beginning of violence for my generation.” Having served on a Grand Jury that tried over 30 murder cases in one month in 1980, the artist became interested in representing everyday murders as well as assassinations of public figures. His subsequent “Little Murders” series, of which Dallas Chaos and Dallas Chaos II are part, offered a critique of violence in contemporary society. Dean drew attention to these and other historical events in order to raise questions not only about violence but also about truth and reality.

Dallas Chaos and Dallas Chaos II encourage a reconsideration of what our media-inspired memory tells us is fact. Dean’s paintings complicate accepted historical narratives and suggest chaos behind the media’s reports, prompting, perhaps, closer consideration of the myriad conspiracy theories regarding President Kennedy’s assassination. For the millions of Americans born after JFK’s death, popular culture and media archives may provide their only familiarity with the events surrounding November 22, 1963. Consequently, paintings such as Dean’s offer important reminders to interrogate our assumptions about historical moments, critically consider what we think we know, and remember that, as the artist hints, there are always more questions to be asked than what we have been told.

Image Credits:

1994.38: Peter Dean, Dallas Chaos, 1981, oil on canvas, 68 x 72 3/16 in., Blanton Museum of Art, Gift of Lorraine Dean and Gregory Dean, 1994

1994.39: Peter Dean, Dallas Chaos II, 1982, oil on canvas, 83 9/16 x 96 1/16 in., Blanton Museum of Art, Gift of Lorraine Dean and Gregory Dean, 1994

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.