Communism acquired many different faces during the twentieth century. In the Soviet Union, it became known as Bolshevism. Named after the political party, led by Vladimir I. Lenin, that defeated the rival Menshevik Party in the October Revolution in 1917, Bolshevism would become the official political dogma of the Soviet Union for decades to come. The domestic response to Lenin’s revolutionary doctrine has inspired nearly a century’s worth of historical literature. Yet one question remains: how did other countries worldwide understand and react to what seemed like a particularly Soviet brand of communism?

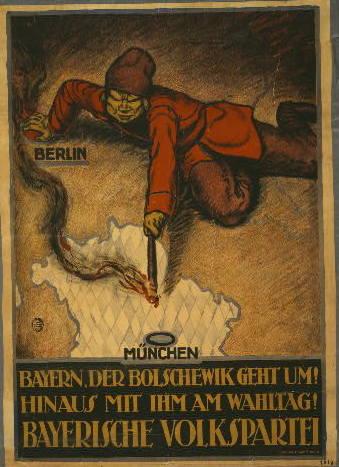

Poster shows a Bolshevik leaning on a map of Europe and setting fire to Bavaria. The text below says: “The Bolshevik is coming! Throw him out on Election Day! Bavarian People’s Party.” (Courtesy of The Library of Congress)

Andrew Straw, a doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin, created “Debating Bolshevism” to answer this very question. While even Stalin questioned the relevance of the term in as late as 1952, one glance at primary and secondary literature from across the globe during the twentieth century demonstrate that while the term may seem obsolete now, understanding what Bolshevism meant, how it was used, and why people had such strong reactions to it is crucial to understanding twentieth century history. The fact that the Soviet Union was the only official Bolshevik state in no way confined the idea of Bolshevism to the USSR. After all, Bolshevism’s own origins came from a transnational dissident group in European exile, one in which Lenin himself claimed membership. After the Bolshevik Revolution, Bolshevism entered into an ideological debate taking place on a world stage. Supporters presented it as an alternative to Western goals and principles of the West. Debating Bolshevism demonstrates that the international community from all points of the political spectrum took it seriously: its detractors maligned its violent excesses, and its supporters exalted its unhinging of imperial powers and rapid change.

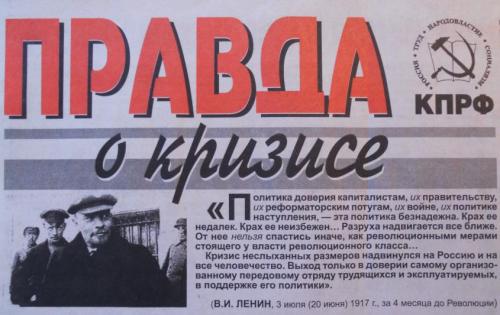

Lenin leads the October Revolution wearing a proletarian workers’ cap on the front page of a 22 January 2009 issue of Pravda. The front-page article is etitled “On the Crisis,” referring to the recent spread of “Occupy Wall Street” protests in cities around the world. The accompanying text states that unemployed workers in Putin’s Russian (unemployment had reach nearly 20% in some areas) are ripe for communist revolution and calls on all concerned to attend a communist rally that was held on January 31 in Moscow.

Further down the page, a picture of pre-revolutionary Russian workers stands side by side with an image of currently unemployed Muscovites to underline the point. In addition, the newspaper includes a flyer for the demonstration that prominently displays the clenched fists of workers.

Mao Zedong was one of the prominent leaders of the 20th century, and the road leading to his successful consolidation of power in the People’s Republic of China was heavily informed by the Bolshevik idea of a radically revolutionary break and guerilla warfare tactics. Mao was a firm believer that a potential revolutionary situation exists in any country where the government consistently fails in its obligation to ensure at least a minimally decent standard of living. While guerilla warfare certainly existed before Bolshevism, Mao was inspired by Bolshevik anti-imperialism, revolutionary self-determination of colonized populations, and civilian participation. Mao’s literature on military strategy drew heavily from Lenin’s On Guerilla Warfare, citing both Lenin’s political ideas and military tactics and sharing the belief that a “people’s” revolution was inevitable. Furthermore, even Western military men viewed Lenin as key to the Marxist revolutionary trends because they thought, “only when Lenin came on the scene did guerilla warfare receive the potent political injection that was to alter its character radically.

But despite the influence, Mao did not adhere to Moscow demands calling for a proletarian revolution, but instead he believed China’s revolutionary potential was housed entirely in the peasantry. Mao “knew and trusted the peasants, and had correctly gauged their revolutionary potential.” At least at this seemed to by the case to Samuel B. Griffith wrote the 1961 introduction to his translation of Mao’s on Guerilla warfare. While Mao’s Cultural Revolution and collectivization would later bring cause take a huge toll on the countryside, his initial use of peasants contrasted with the distrust and disdain Lenin and especially Stalin had for the Russian peasantry. Mao’s view was a such source of dissension between him and the Kremlin that Moscow even sanctioned the attempt by Zhou Enlai and a group known as the “28 Bolsheviks” who tried to replace Mao in 1934. These tensions would remain and only grow into the Sino-Soviet split during the Cold War.

Visit Andrew Straw’s graduate student homepage.

University of Texas at Austin – History Department

(Professor: Jeremi Suri)

Photo credits:

Zhou Zhenbiao, “Marx’s – The Glory of Mao’s Ideologies Brightens Up the New China,” Peking, 1952

People Fine Arts via The Library of Congress