by Elizabeth O’Brien

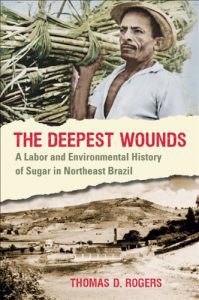

There is a vast historiography on worker strikes and resistance to economic exploitation in Latin America and Brazil, yet most scholars disregard the environmental backdrop to struggles over land, labor, and resources. Aiming to fill this lacuna, The Deepest Wounds is a combination of labor and environmental histories, and it has elements of commodity-chain and literary analysis as well. Examining over four centuries of sugar production in Pernambuco, Brazil, Thomas Rogers demonstrates that  sugar monocropping not only changed the environment, it also altered the nature of politics, social dynamics, and labor mobilization in the region. Above all, Rogers claims that the exploitation of nature and labor shaped the power dynamics that harmed workers and damaged the land itself.

sugar monocropping not only changed the environment, it also altered the nature of politics, social dynamics, and labor mobilization in the region. Above all, Rogers claims that the exploitation of nature and labor shaped the power dynamics that harmed workers and damaged the land itself.

Rogers claims that discourses of landscape underscored the transition from slavery to a new paradigm that relied on old logic: the planter class still saw the landscape and the workers as objects to be controlled. Pointing to literature for evidence, Rogers proposes that novelist Joaquim Nabuco’s nostalgia for a landscape actually represented his longing for the paternalistic racism of slavery. José Lins de Rego and Gilberto Freyre, on the other hand, protested the havoc that cane monoculture wrought on humans and nature alike. Workers, for their part, allegedly used a language of captivity to describe post-slavery social conditions, and, by highlighting worker poverty and lack of opportunity, Rogers points to the persistence of slave-like exploitation throughout the twentieth-century.

Rogers chronicles the development of usinas (sugar mills), which grew immensely between the mid-1930s and the 1950s. Powerful families still controlled the mills, but centralization and modernization occurred under the Vargas regime. For example, the use of fertilizer in the 1940s led one producer to increase sugar output by 220% in just a decade and a half. The establishment of the Institute of Sugar and Alcohol (IAA sparked economic and labor reforms. Yet rationalization was patchy in these decades and worker-patron relations still functioned as patronage. By paying close attention to agricultural processes, Rogers shows that modernization altered systems of work without eliminating oppression. Agrarian reform laws, for example, required bosses to pay workers by the task instead of by the day. Patrons manipulated this system so that it did not result in higher wages: instead, workers labored in tasks for longer periods of time.

Many laborers resisted abuse and exploitation, and their struggles evoked solidarity from union organizers, communists, and Church groups. Overt politicization of the sugar fields began in the 1940s, and the first rural union emerged in 1946. Communist leaders organized a conference of rural workers in 1954. Shortly thereafter, 550 “suspected militants” were arrested and the regional committee collapsed. Peasant leagues soon spread throughout the region, and the Sociedade Agro-Pecuária de Pernambuco (SAAP) gained particular prominence. Governor Sampaio selectively acquiesced to union demands, eventually distributing land to members of the peasant league. Not surprisingly, some mill-owners resented the mobilizations and retaliated by shooting and killing union delegates. As a result of continued agitation and struggle, November 1963 saw the biggest strike in Brazil’s rural history: an estimated 90% of the region’s workers (200,000 people) halted production in order to protest abuses in the cane fields.

By focusing on environmental history, Rogers shows that the 1960s was an important decade for additional reasons. Scientists and mill owners introduced CO 331, a strain of sugar cane known as 3X, with the goal of increasing cane output. By 1963, mill owners were mono-cropping the strain, and 3X accounted for about 80% of state’s harvest. The per-hectare weight of yields rose, but the amount of sugar per ton of cane fell dramatically — by as much as 20 kilograms per ton between the mid-1950s and 1964. The combination of economic pressure and worker strikes weakened production, and enhanced state opportunities for intervention. Wielding the language of science and technocracy, the military regime stepped in to assert control over sugar production in 1964.

Under the military regime, agricultural workers experienced new forms of state control. The state issued identification cards designed to transform anonymous workers into “fichados,” or documented employees. Women often secured cards instead of working alongside men without their own proper wages. Characterizing worker incorporation into the state as proletarianization, Rogers points out that laborers could benefit from new legal channels and use them to challenge patrons. Nevertheless, oppressed and underpaid workers continued to organize strikes in order to protest labor abuses, and the state began to repress workers to a greater degree than before.

State incorporation did not free workers, and sugar cane production continued to pollute the environment and generate proletarian struggle.

Photo Credits:

A Brazilian worker harvests sugar cane (Image courtesy of Webzdarma.cz)