In “The European Avant-Garde in Print” (REE 325), students explored the unique and vibrant print culture in Central Europe between the two world wars and the social and political context that produced it. I sought to expose students to the networked qualities of magazines that were published in Czech, Hungarian, Serbo-Croatian, Polish, and German. We examined contributor lists, the aesthetic qualities of the “New Typography,” and the way that the magazines cross promoted each other through advertisement.

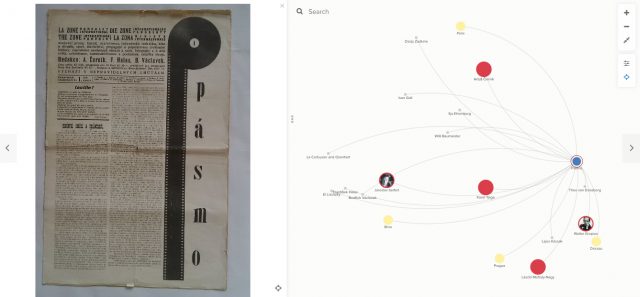

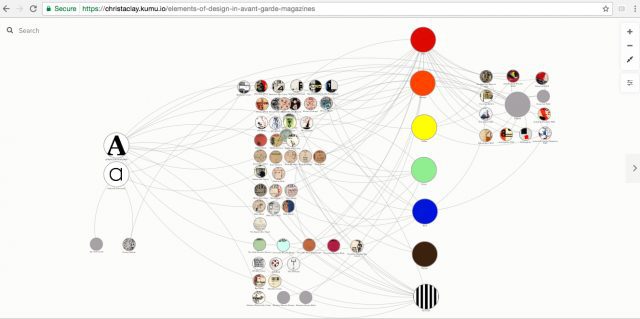

Students discovered the transnational and multilingual interconnectivity of these magazines through the use of various digital mapping and open source publishing resources, such as Kumu and Scalar. Using Kumu’s Social Network Analysis tool, for instance, I could help students visualize how one figure, such as Karel Teige, the leading member of the leftist Czech avant-garde group Devětsil, leveraged his connections with editors elsewhere to make magazines that facilitated relations with major figures of a pan-European avant-garde. To offer just one example, through the Brno-based magazine, Pásmo, the Czech avant-garde actively collaborated with the Russian born and Berlin-based artist El Lissitzky, the German Bauhaus director Walter Gropius, and French-German correspondent Yvan Goll.

(via author)

I used digital mapping in my lectures to make this fluid exchange more concrete and dynamic for students. Then, a major component of the class was built around students developing their own digital mapping and visualization group projects. In this way, students had the opportunity to engage critically and interactively with the materials covered in the course.

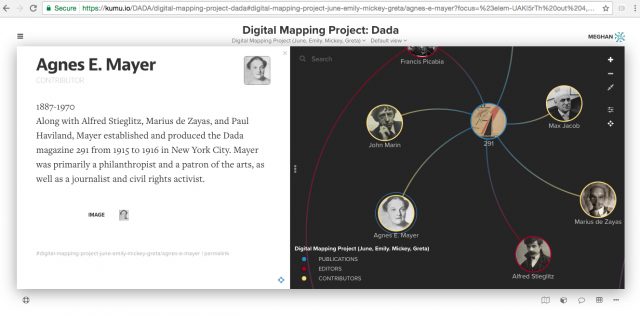

One group drew on our extensive discussion of Dada periodicals published both in Europe and the United States—which we had the opportunity to view in person at the Harry Ransom Center—to reveal how some prominent artists appeared in Dada publications on both sides of the Atlantic. They also used their map to comment on who did not figure in these publications—namely, women, with the exception of the New York-based 291 contributor Agnes Meyer, whom they featured.

Another group of students chose to document connections across a series of publications not via their contributors or geographic locale, but rather in relation to shared principles of design, such as color, shape, and textual form. This group even built their map to visually reflect in its own design the various components that they chose to highlight.

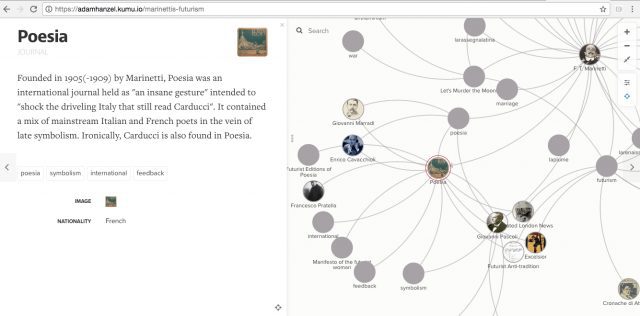

Another project focused on a single magazine—the Italian Poesia—to make manifest the various personal connections between the leading figure of Italian Futurism, F.T. Marinetti, and other artists and authors related to the movement.

The digital mapping component of the course was largely made possible with the assistance of UT’s Slavic and Digital Scholarship librarian, Ian Goodale, who made multiple class visits in which students had the opportunity to workshop their digital projects, and who also held weekly office hours in the Slavic Department. Ian also created a Scalar platform that holds all the mapping projects in one place, with the Kumu maps embedded, and includes other analytical content generated by students, allowing for further connections to be drawn across the group projects.

I observe in my own classroom, and in the work of my peers both across UT and at other institutions, the need for universities and colleges to commit to allocating funding for their libraries so that they may train and hire staff who are able to support digital pedagogy. For example, this past semester, Ian Goodale also helped my colleague in the Slavic Department, Vlad Beronja, create another digital project, Yugoslav Punk, with students in his course on Punks & Divas in Southeastern Europe.

Another aim in teaching “The European Avant-Garde in Print,” was to expose students to non-European periodicals, to explore the variety of responses to inter-war social and political conditions, and also to find actors outside of a European male cohort largely not represented in the Central European set. By giving students the opportunity to create their own mapping projects, I hoped to reveal unexpected connections between these cultural products. There is more work to be done in achieving these goals in a future iteration of this course, and data visualization and digital mapping tools will facilitate students’ active learning towards this end.![]()

You may also like:

Digital Learning: Starting from Scratch, by Joan Neuberger

Media and Politics From the Prague Spring Archive, by Ian Goodale

The Prague Spring Archive Project, by Mary Neuburger and Ian Goodale![]()

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.