In what amounted to the last act of World War II, US forces dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, and another on Nagasaki three days later. Ever since, controversy has swirled around the decision to drop those bombs and annihilate those two cities. But exactly who made that decision, and how did it come about? Conventionally, of course, the decision is ascribed to President Harry Truman, but there is in fact very little documentary evidence that he ever made an affirmative decision to drop the bombs. Instead, the most that can be said with certainty is that he did not intervene to stop a process that had already acquired enormous momentum even before he became president on Franklin Roosevelt’s death in April 1945.

Remarkable collections of primary documents, now readily available online, shed substantial light on the story of the development and use of the first atomic bombs. Two of the best collections are those maintained by the National Security Archive and by the Truman Library. On the NSA website, for instance, we find a long report General Leslie Groves, the head of the Manhattan Project, prepared for Secretary of War Stimson. The meeting on April 25, 1945, at which Groves and Secretary of War Henry Stimson delivered the gist of this report to Truman was the first time the new president was given more than the barest hint about the new weapons that had been in development, at enormous expense, for the past three and a half years. Groves’s memo gives a fairly full account of how atomic bombs would work and of the prospects that they would be ready to in less than four months. How much of all this, or of the shorter memo Stimson prepared, Truman really absorbed is not clear, but by the time the first plutonium implosion bomb was detonated in the New Mexico desert on July 16, 1945, Truman had certainly grasped that such bombs might play a pivotal role in ending the war with Japan, as well as in postwar relations with the Soviet Union.

Remarkable collections of primary documents, now readily available online, shed substantial light on the story of the development and use of the first atomic bombs. Two of the best collections are those maintained by the National Security Archive and by the Truman Library. On the NSA website, for instance, we find a long report General Leslie Groves, the head of the Manhattan Project, prepared for Secretary of War Stimson. The meeting on April 25, 1945, at which Groves and Secretary of War Henry Stimson delivered the gist of this report to Truman was the first time the new president was given more than the barest hint about the new weapons that had been in development, at enormous expense, for the past three and a half years. Groves’s memo gives a fairly full account of how atomic bombs would work and of the prospects that they would be ready to in less than four months. How much of all this, or of the shorter memo Stimson prepared, Truman really absorbed is not clear, but by the time the first plutonium implosion bomb was detonated in the New Mexico desert on July 16, 1945, Truman had certainly grasped that such bombs might play a pivotal role in ending the war with Japan, as well as in postwar relations with the Soviet Union.

In their effort to find the moment when Truman made “the great decision” to use atomic bombs against Japan, several historians have latched onto a memo (posted on the Truman Library website) that Stimson sent to Truman on July 30, 1945, and have focused in particular on the reply Truman scrawled on its back. “Suggestions approved,” he wrote.”Release when ready but not sooner than August 2. [signed] HST.” In his well known biography Truman (1992), David McCullough declared that “The time had come for Truman to give the final go-ahead for the bomb. This was the moment, the decision only he could make.” But examination of Stimson’s memo shows clearly that it was not about getting approval to release the bombs over Japan, but only about releasing a carefully crafted public statement to the press once the first bomb had been dropped. Approving a press release appears to be the closest President Truman ever came, at least in writing, to making a positive decision concerning the first use of nuclear weapons.

In their effort to find the moment when Truman made “the great decision” to use atomic bombs against Japan, several historians have latched onto a memo (posted on the Truman Library website) that Stimson sent to Truman on July 30, 1945, and have focused in particular on the reply Truman scrawled on its back. “Suggestions approved,” he wrote.”Release when ready but not sooner than August 2. [signed] HST.” In his well known biography Truman (1992), David McCullough declared that “The time had come for Truman to give the final go-ahead for the bomb. This was the moment, the decision only he could make.” But examination of Stimson’s memo shows clearly that it was not about getting approval to release the bombs over Japan, but only about releasing a carefully crafted public statement to the press once the first bomb had been dropped. Approving a press release appears to be the closest President Truman ever came, at least in writing, to making a positive decision concerning the first use of nuclear weapons.

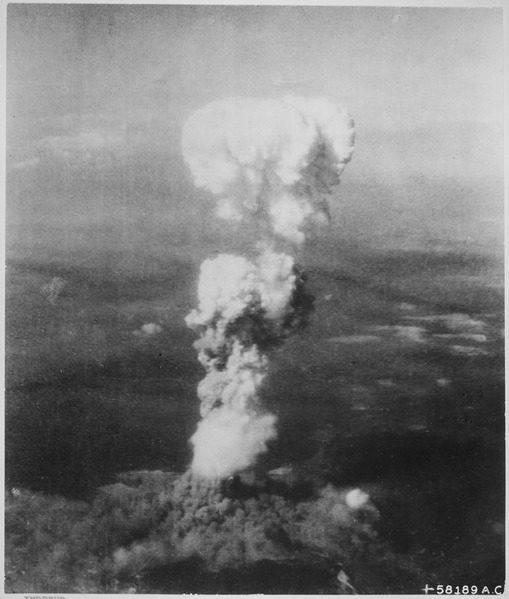

At the time this photo was made, smoke billowed 20,000 feet above Hiroshima while smoke from the burst of the first atomic bomb had spread over 10,000 feet on the target at the base of the rising column.Two planes of the 509th Composite Group, part of the 313th Wing of the 20th Air Force, participated in this mission, one to carry the bomb, the other to act as escort, 08/06/1945, Author Unknown, National Archives and Records Administration

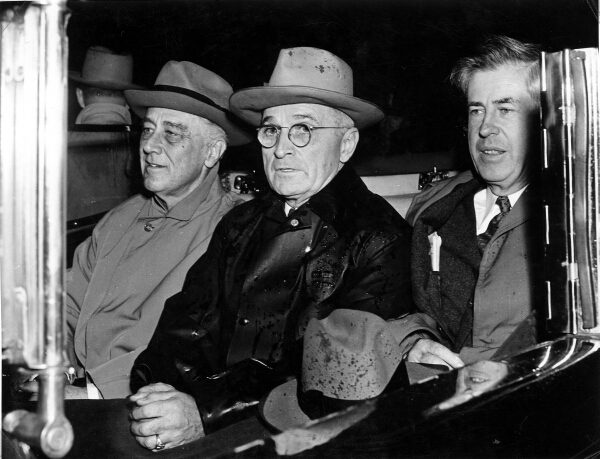

President Roosevelt, Vice-President-elect Truman, Vice-President Wallace, by Abbie Rowe, Truman Library

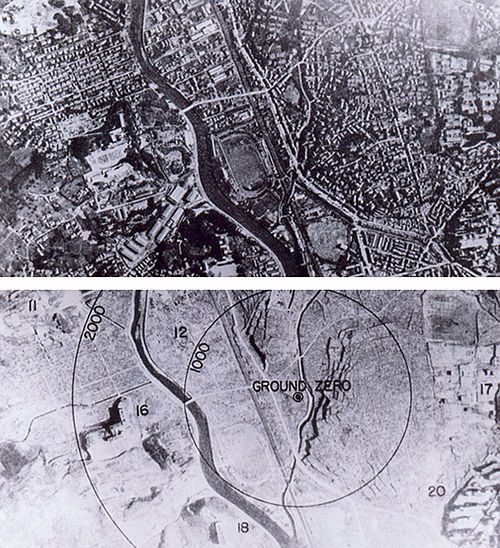

Nagasaki, Japan, before and after the atomic bombing of August 9, 1945, U.S National Archives

All via Wikimedia Commons